The impressionist artists of "Société Anonyme" broke from tradition not only in style, but also through the portrayal of modern domestic life, with particular attention to women. Edgar Degas, "At the Races in the Countryside," 1869, oil on canvas, displayed in National Gallery of Art's "Paris 1874: The Impressionist Moment" exhibit. (National Gallery of Art)

Two seemingly unrelated art exhibits opened mere blocks from one another in Washington, D.C., this September, each widening the perspectives included in social and ecclesial narratives.

The National Gallery displayed "Paris 1874: The Impressionist Moment," which contrasts works from the first Impressionist show, "Société Anonyme," with the competing exhibit of the time, "The Paris Salon."

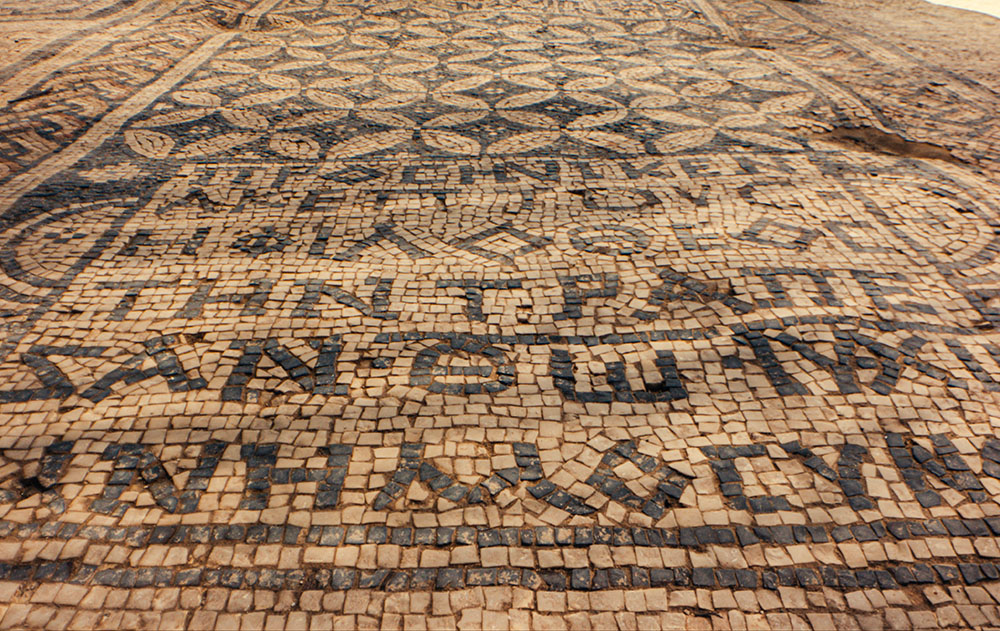

Meanwhile, the Museum of the Bible offered the first public viewing of "The Megiddo Mosaic: Foundations of Faith," which dates to A.D. 230 and casts a fresh light on the early Christian church.

Berthe Morisot, "The Mother and Sister of the Artist," 1869/1870, oil on canvas (National Gallery of Art)

At the opening of "The Megiddo Mosaic," Museum of the Bible CEO Carlos Campo noted that "Paris 1874" and "The Megiddo Mosaic" were alike in that each requires the viewer to take a step back to see the broad, unifying picture. This statement is true of artistic form as well as socio-historical import: Both exhibits explore women's roles, political division and the beauty of a broader cultural lens.

Touted as the birth of modern painting, "Société Anonyme" broke from tradition not only in style, but also through the portrayal of modern domestic life, with particular attention to women. Redefining what was worthy of the public gaze, the impressionists portrayed scenes of everyday life, family and the domestic sphere.

Rather than painting women in all their finery, as mere ornaments of society, the artists showed a more intimate perspective.

Berthe Morisot showcased two paintings of her sister in "Société Anonyme": one titled "The Mother and Sister of the Artist" and the other "The Cradle," the latter of which depicts the woman gazing down at her child asleep in a bassinet.

Edgar Degas' "At the Races in the Countryside" includes a mother (or wet-nurse) breastfeeding. While such portrayals may not seem groundbreaking today, they would certainly not have been welcome at "The Paris Salon" at the time.

"The Megiddo Mosaic," discovered in 2005, is believed to have served as the floor of an early church prayer hall, an ornate rug of sorts that would have supported the Communion table.

The Akeptous inscription that adorns the Megiddo Mosaic, currently on exhibit at the Museum of the Bible, reads, "The God-loving Akeptous has offered the table to God Jesus Christ as a memorial." (Museum of the Bible)

Three inscriptions adorn the mosaic; the one on the western side of the south panel — which reads, "The God-loving Akeptous has offered the table to God Jesus Christ as a memorial" — has been hailed as the most important in that it reaffirms the early church's belief in the divinity of Jesus Christ.

Akeptous — notably, a female — is credited as having donated the funds for the Communion table. This, when considered in conjunction with the fact that the eastern side of the south panel bears the names of four more females ("remember Primilla and Cyriaca and Dorthea, and lastly, Chreste"), emphasizes the importance of women in the early church. While we do not know the exact roles of these individuals — possibly martyrs, benefactors, ministers or scholars — the inscription of their names in such a place of honor speaks volumes.

Advertisement

Both exhibits memorialize the artists and patrons who chose to go against the status quo and dedicate their life to something new and groundbreaking. The Musée d'Orsay described the budding impressionist artists of the "Société Anonyme" as a "clan of rebels," intent on breaking from traditional artistic renderings and lofty themes.

With the pieces displayed together in "Paris 1874," the viewer can clearly see the stark differences; namely, the impressionists' work to draw the viewer closer, inviting an intimacy of perspective that the "Salon" paintings do not. The impressionists' work spans a broader view of the human experience in the modern world, capturing the tender, everyday moments of life in various socioeconomic levels.

"Paris 1874" and "The Megiddo Mosaic," like all good art exhibits, draw us in while widening our perspectives. By recognizing (overwhelmingly female) individuals who were customarily sidelined, each paints a more inclusive picture of their moments in history.

"Paris 1874" is on display at the National Gallery through Jan. 19, 2025. "The Megiddo Mosaic: Foundations of Faith" is on display at the Museum of the Bible through July 6, 2025.