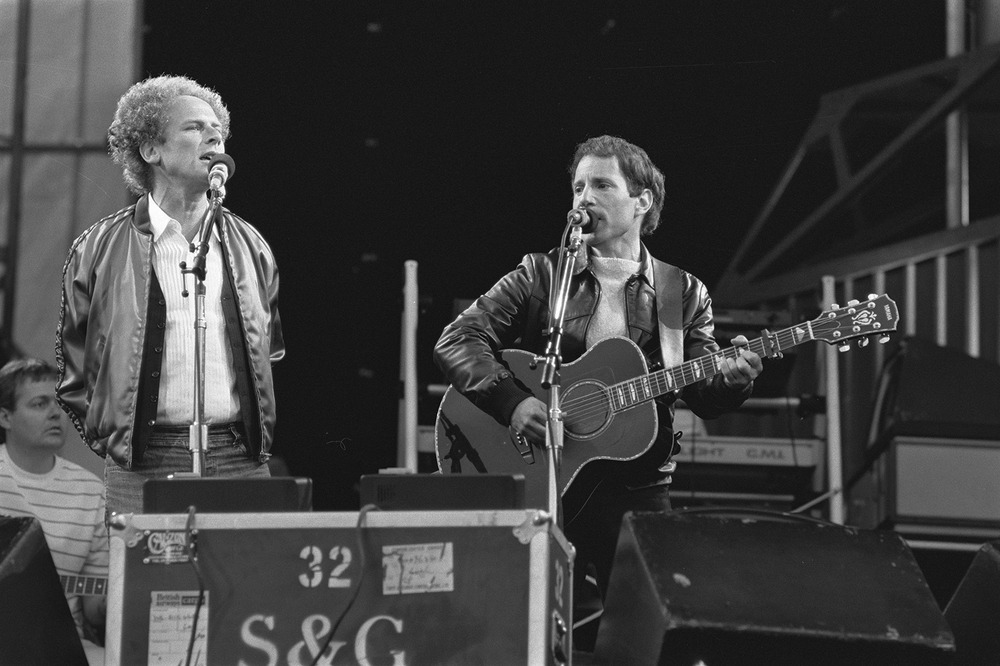

Art Garfunkel, left, and Paul Simon, the duo of Simon & Garfunkel, perform in the Netherlands in 1982. (Rob Bogaerts/Anefo/Wikipedia/Creative Commons)

One song has stuck with Julio Cuellar Gonzales for practically his entire life. Among his first memories of church in the 1970s in Villa Serrano, a town in the Bolivian region of Chuquisaca, Cuellar remembers singing a specific version of the Our Father.

At the time, Cuellar thought it was written by a priest. He didn’t imagine that the beloved Our Father’s tune was actually written by Paul Simon for Simon & Garfunkel’s 1960s hit ”The Sound of Silence.”

The words were different from the typical Our Father prayer. “Our Father, who art in those who truly love. May the kingdom that you promised us come soon to our hearts. The love that your son left us, may that love dwell in us,” began the song that Cuellar sang in Spanish. In the middle of the song, as a zampoña, a traditional Andean pan flute, played the melody, parishioners said the traditional Our Father together with the words from Matthew 6.

From Villa Serrano, “The Sound of Silence” Our Father followed Cuellar when he moved to Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the largest city in Bolivia. “This was one of the people’s favorite songs and ours too,” he said.

Years later, after working as a musician on cruise ships in Mexico and then immigrating to Virginia, he found a Spanish Mass and heard it again. “It connected me to my childhood,” he said.

Pedro Rubalcava, the director of Oregon Catholic Press’ label group, said that “The Sound of Silence” version of the Our Father has been widespread throughout Latin America and U.S. Latino communities for the last few decades. There are variations in the words and instrumentation in different communities.

For Cuellar, even when he finally learned the tune’s origin, it still felt Andean to him: “It sounds to me like the melancholy, the melody, the sweetness of the music of the Andes.”

While there’s no proof that Simon took inspiration for “The Sound of Silence” from the Andes, he later used an Andean tune in “El Condor Pasa,” a single on Simon & Garfunkel’s Grammy-winning 1970 album, “Bridge Over Troubled Water.”

While Simon recorded the vocals with permission over a recording by a French Andean band, Los Incas, believing that the melody came from a folk tune, the melody actually came from Daniel Alomía Robles’ 1913 Peruvian musical theater piece called “El Cóndor Pasa.”

Valdimar Hafstein, a professor of folkloristics/ethnology at the University of Iceland, wrote in a 2018 book, “Making Intangible Heritage: El Condor Pasa and Other Stories From UNESCO,” that, given Robles’ travel through the Amazon and Andes to collect myths and music, part of a widespread tradition of “collector-composers,” it can be hard to describe the tune as either Robles’ original or an arrangement.

When Robles’ son sued Simon because his father’s composition was registered in the U.S. copyright system, Simon settled, with the son calling it “almost a friendly case.”

“The Sound of Silence” Our Father came back into Cuellar’s life when he decided to begin recording Christian music after years of focusing on secular music. “I felt like I had a debt to the Lord for the gift of the music,” Cuellar explained. When he told the Episcopal church where he was a music minister that he planned to make a record, people kept coming up to him after Mass asking for a recording of the Our Father.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, as Cuellar took walks in the woods around Virginia’s Lake Braddock to connect with God and escape the fear and uncertainty, he was inspired to ask his wife to film him singing the Our Father by a stream.

“We need something that will give us strength,” Cuellar told her. After his friend with experience in video editing helped polish the video, he posted it to YouTube “as a cover” because he wasn’t the author. Among many other versions of “The Sound of Silence” Our Father, Cuellar’s now has more than 23 million views.

Julio Cuellar Gonzales in the “Padre Nuestro,” or “Our Father,” video that has 23 million views. (Video screen grab)

“I’ve made music my whole life,” Cuellar said. “I’ve never reached the number of people that I’ve been able to reach with this marvelous work from the maestro Paul Simon.”

“It’s a miracle from God. It’s a message from God what has happened with” the song, Cuellar said.

But not everybody likes the version of the Our Father. Cuellar said that, while the positive comments vastly outnumber the negative, he’s heard people call it a “diabolical song,” criticizing everything from the changed words in the Our Father to the Andean instrumentation. Other people simply say that it’s not appropriate for services.

“I’m a child of God, and the devil doesn’t arrive at my house because God is here,” Cuellar said. “I’m not an expert in Christian music, but I’m an obedient person who tries to listen to the voice of God in the silence.”

“I’ve made music my whole life,” Cuellar said. “I’ve never reached the number of people that I’ve been able to reach with this marvelous work from the maestro Paul Simon. It’s a miracle from God."

Rubalcava said that Philadelphia Archbishop Nelson Pérez has taught that Catholics should not sing the version for a few reasons. First, the words to the Our Father should not be changed, especially in the liturgy. Secondly, “The Sound of Silence” forms part of the soundtrack for “The Graduate,” a 1967 movie where an extramarital affair is a major storyline.

Ireri E. Chávez-Bárcenas, an assistant professor of music at Bowdoin College and a musicologist who studies sacred song in the Hispanic world, said that the debate around the Our Father with the melody of “The Sound of Silence” draws on centuries-old controversy.

Setting a liturgical or devotional text to a known secular melody has been a “common technique used by the Catholic Church since before the Middle Ages,” Chávez-Bárcenas told Religion News Service in an email, explaining that the technique is called contrafactum.

However, Chávez-Bárcenas said the technique has always been controversial, with the best known policies against it coming during the Counter-Reformation. “In Latin America, Franciscans and Jesuits always advocated for the adaptation of liturgical texts in the local languages, songs, and musical styles,” Chávez-Bárcenas wrote.

Advertisement

“The Sound of Silence” is just one instance of Latino Catholics’ use of pop song melodies for devotional and liturgical music, Rubalcava said, citing an offertory song called “Saber que Vendrás” that uses Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” as its tune, various liturgical adaptations of “Jesus Christ Superstar” melodies and a Marian devotional song “Mi Virgen Bella” that uses the melody of Juan Gabriel’s “Amor Eterno.”

“It’s illegal because you’re plagiarizing, and probably without permission,” said Rubalcava, saying copyright law is another issue with “The Sound of Silence” version of the Our Father.

Rubalcava said that these sacred versions of popular songs are passed from one church musician to another informally without official approval from broader church structures. After the Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago was found guilty in 1984 of illegally photocopying the music of a religious composer, the U.S. Catholic bishops have been very serious about respecting copyright permissions, Rubalcava said.

There’s an attitude, Rubalcava said, that exists everywhere but particularly in Latin America “that anything for God should be free.” Rubalcava said, “People don’t think there’s a good reason for paying for composers, artists that are trying to make a living or trying to raise money to record some music.”

Rubalcava said that liturgical, musical and theological formation is needed so that Catholics respect that “the laborer gets their due.”

E. Michael Harrington, a professor in music copyright and intellectual property matters at Berklee Online, said that what was going on was “a problem,” but “not a really serious one.”

“Technically, they’re making a derivative work,” Harrington explained. “If you take someone else’s copyrighted material, something they authored and they own the copyright in, if you take that and change it, you’re violating their rights.”

To add new words to “The Sound of Silence” melody, musicians need to get permission from the publisher, Harrington said.

But, Harrington explained, the publisher likely will not sue “because it’s an organic thing that was unplanned and people are doing it, but they’re not profiting.”

Harrington said church leaders were taking the right steps by not endorsing the use of the melody, but he also said that they could seek a license from the publisher if they were interested in using it.

Reading the comments on his video, Cuellar sees his involvement with the Our Father as serving God. “It’s a song that touches the heart,” he said. The comments say things like, “This song gives me peace. This song gives me hope. It gives me strength.”