Earlier this year, Fr. Aleksandr Bohomoz and Basilian Sr. Lucia Murashko prepare to enter a triage center in Velykomykhajlivka in southeastern Ukraine. (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Editor's note: Chris Herlinger, Global Sisters Report international correspondent, has reported multiple times from Ukraine since Russia's full-scale invasion of the country in 2022. A new book, Solidarity and Mercy: The Power of Christian Humanitarian Efforts in Ukraine (Morehouse Publishing), compiles his work for GSR and NCR with new additional reporting. In these excerpts adapted from the book, Herlinger profiles Father Aleksandr Bohomoz, a Catholic cleric who left Russia-occupied Ukraine in late 2022.

On a February evening in 2024, two years into a war that no Ukrainian sought or desired, late-afternoon darkness descended on the village of Velykomykhajlivka in southeastern Ukraine. All streetlights were blacked out — so as to prevent drone attacks — and the windows of a triage center for wounded soldiers near the front lines were boarded up.

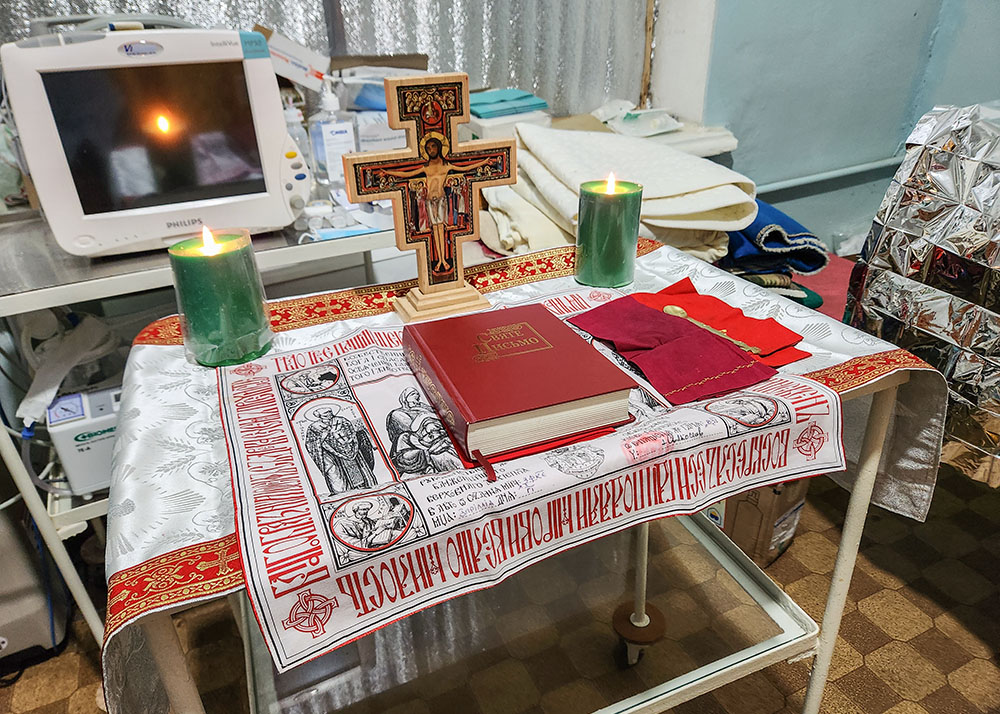

The village's unpaved streets were muddy, but Fr. Aleksandr Bohomoz and Basilian Sr. Lucia Murashko, having recited the rosary on the way to their destination, bounded out of a car with the sacred vessels needed for Mass, or, as the Ukrainians call it, the Divine Liturgy. They carried with them wine, hosts, a chalice, a small crucifix in the Byzantine style, two candles, two altar cloths and a prayer book.

Once inside, the two carefully placed everything on a medical table in a dimly lit public space. The triage center, a renovated clinic and hospital, was hushed and quiet. Father Aleksandr read a passage from Matthew 22:37-40 in which a lawyer asks Jesus what is the greatest commandment.

Jesus responds:

"You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind." This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: "You shall love your neighbor as yourself." On these two commandments hang all the Law and the prophets.

On this particular night, only one soldier, a young man named Sasha, attended the half-hour service — the numbers of weekly attendees have varied over the past two years, from only a few to more than a dozen. But neither Father Aleksandr nor Sister Lucia, both members of Ukraine's Greek Catholic Church, were put off by the small turnout.

At a triage center in Velykomykhajlivka in southeastern Ukraine, Fr. Aleksandr Bohomoz and Basilian Sr. Lucia Murashko placed the sacred vessels needed for Mass, or, as the Ukrainians call it, the Divine Liturgy, on a medical table. (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

What was important was being a witness and participant in the miracle that, for Catholics and other Christians, transcends immediate tragedies and lightens a community's burdens and cares — in this case, a medical team's worry about drones, a Russian attack, and the possible influx, at any moment, of the wounded or sick. Or the fear of war's irrational violence — a force well known to Ukrainians for two-plus years now, with hospitals, schools and theaters, churches, homes and apartment buildings all fallen to Russian bombardments and shelling.

For a few brief moments, the dimly lit workaday medical space was altered and transformed by tradition, the belief in miracle and resurrection, transcendence and an abiding sense of hope — for the future of Ukraine and its people, no matter what their religious affiliation.

The ride back to the city of Zaporizhzhia through a darkened, unwelcoming and barren landscape took just over an hour — the front line may have become more distant but was never fully out of mind or thought. Father Aleksandr and Sister Lucia spoke little — they were quiet and reflective.

I later asked Sister Lucia if it bothered her that only one soldier had participated in the service.

No, she said, the act of witnessing on a dark, quiet Sunday evening in a war zone was more than enough. "Now it is so," she told me. "It can be just one. I think we do what we have to do. We pray in that place for all those people. Our prayers are protection for all of these locations. God hears our prayers there even when medical staff or soldiers do not always understand the value of the prayers."

Basilian Sr. Lucia Murashko during early morning hours at the convent run by the Sisters of the Order of St. Basil the Great in Zaporizhzia, southeastern Ukraine (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

A few days later, I was invited to meet Father Aleksandr at the Zaporizhzhia convent where Sister Lucia is the prioress and listened to him recount experiences that were, as I discovered, almost cinematic in scale.

Father Aleksandr, 35, had previously worked in Melitopol, which has been under Russian control since March 2022. A native of the Kherson region, Father Aleksandr was part of a group of Ukrainian Catholic clergy who found a welcome in the east and saw the number of churches increase before the full-scale invasion.

Whereas there was only one Ukrainian Catholic priest in the region in 2010, there were five or six by 2022, and each took care of three to four parishes. In all, there were six priests who remained in the occupied areas: two were eventually imprisoned, two escaped and two were forcibly deported, Father Aleksandr being one of them.

Father Aleksandr spoke of his experiences calmly, in a somewhat matter-of-fact tone. Over a meal of cheese pizza that the sisters had ordered in, he told me that he had spoken of his experiences to Ukrainian journalists, and so the narrative came easily to him.

His body language did not betray much emotion at first. But as he spoke of what was a remarkable experience, his pace of speaking picked up some.

Father Aleksandr told me that though Russian tanks rolled into Melitopol on Feb. 25, 2022, he was able to stay nine months before being deported — an experience he said that could have been far worse. Unlike another priest, for example, he was not beaten. But still, the experience was unnerving.

Fr. Aleksandr Bohomoz after celebrating Mass at the convent run by the Sisters of the Order of St. Basil the Great in Zaporizhzia, southeastern Ukraine (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

In all, he was interrogated seven times over the course of nine months, and each time he resisted what he was told was the "proper way" to practice his faith. What resulted in the final expulsion was his refusal to divulge confessions, and ultimately his interrogators took personal items and documents and seized his car. During this time, someone armed with a machine gun watched after him. As a founder of a local Knights of Columbus chapter, Father Aleksandr and the Knights were accused of being American spies.

Yet, he was still spared being imprisoned or beaten.

"There's no explanation for it," he said, repeating what Ivan, a teenager I had met at the convent who had related his experiences about life in occupied territory, said of a teacher whose car was shot at. It's not rational. "I'm lucky to be alive. ... It's a miracle."

But it is a miracle also given his final experiences in the occupied areas: On Dec. 1, 2022, on a cold, cloudless day, Father Aleksandr was dropped off at the so-called gray zone and told he had to walk 9 miles to the Ukrainian side — all while shelling erupted.

He walked along a highway, with rockets soaring over his head, and ran into a group of Russian soldiers who asked what he was doing. Wearing his clerical garb, he said he was headed toward Zaporizhzhia, garnering laughs from the Russians.

"I didn't explain that I was deported," he said, figuring that telling the story would complicate things. Father Aleksandr knew the area a bit and knew of a small bridge he might cross. However, he found that that bridge had been blown up.

Along the way, he met an elderly woman who warned him about land mines ahead. "She said, 'Don't go there.' " He recalled, "If I hadn't been told that, I might have died. That was another miracle I experienced."

Advertisement

Father Aleksandr recited the rosary throughout the ordeal and knew there were people who were praying for him. "I believe faith and constant prayer guided me," he said. So did a sense of urgency — he walked quickly, almost running, and though it was cold, took off his jacket due to the rapid pace, adrenaline rush and anxiety he felt. "I almost flew there," he recounted.

He later experienced another miracle. At the border, "someone screamed my name." It was a young soldier who had been a member of one of his parishes. He did not recognize the young man at first, Father Aleksandr admitted. "I was confused."

The front line is as long as 600 miles, so the chances of seeing this young man were minimal at best. "He ran to me with a bulletproof vest — I hugged him so hard," he said, recalling tearing up.

This all happened in one day, he marveled. He was arrested at nine thirty in the morning and arrived in a safe zone by five in the afternoon. The sun was just setting — and it was cold.

What came next?

"I wasn't sure where I'd spend the night," but the young soldier took Father Aleksandr to his commander, and he was able to get a lift to a nearby police station, where he recounted his story to authorities, told them he was fine, and eventually arrived in Zaporizhzhia.

"The way things came together, I was blessed." Still, Father Aleksandr's initial feelings focused on fears that he had let his parishioners down. "I felt I left my people there and felt lost, a bit of guilt," he said.

At a triage center in Velykomykhajlivka in southeastern Ukraine, Fr. Aleksandr Bohomoz prepares the sacred vessels needed for Mass. (NCR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Father Aleksandr has made his peace, though, serving in Zaporizhzhia, but is still eager to return to Melitopol. He said Zaporizhzhia "has become dear to me" and praises Sister Lucia and the sisters for welcoming him. He now works in four parishes in the Zaporizhzhia area, but he feels it is a temporary dwelling.

His two real homes, he said, are in heaven and in Melitopol.

Father Aleksandr shared that he has forgiven "the guys who pursued me, the Russians," but added that he feels sorry for the Russian people.

Given the horrors he experienced, he believes, using biblical imagery, that they are possessed by demons and "led by the devil."

"I pray for them every day and pray for their conversion," he told me. "I try not to think about it, though I do feel a lot of pain and grievance. I do think about close friends of mine who have died. I have lots of pain, but no, I don't feel hatred for them."

That sense of hard-earned benevolence comes through in his work as a cleric. In addition to seeing Father Aleksandr work with Sister Lucia during our visit to the military triage center in Velykomykhajlivka, I had also seen him preside at Mass at the convent. He was centered, assured and even happy.

Father Aleksandr had escaped from a kind of hell — but being fortunate to have touched the light, had affirmed the promise of his faith.