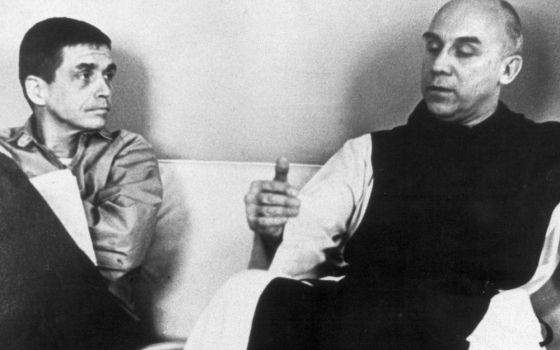

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan died April 30 at 94. He is pictured in a 2002 photo in New York. (CNS/Bob Roller)

He was priest, prophet, poet and prisoner. Anti-war crusader Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan died Saturday, April 30, of natural causes at Murray-Weigel Hall, a Jesuit health care facility in the Bronx, nine days shy of his 95th birthday.

One of the most controversial figures in the 20th century U.S. Church, Berrigan, along with his late brother, Philip, burned draft files and hammered on nuclear weapons components, in acts of resistance to U.S. militarism. The Berrigan brothers' felonious forms of nonviolent protest led a nation of Catholics, and millions of others, to both loathe and love the brothers, who together made the cover of Time magazine in 1971 for their work in opposition to the Vietnam War.

Berrigan's family 'experienced incredible grace' April 30

On the morning of April 30, Dan's sister-in-law and Philip's widow, Elizabeth McAlister, and her three children, Frida, Jerry and Kate, were at a planned family weekend outside Philadelphia when they received a call that Dan had taken a turn for the worse and may not survive the night.

"It was a kind of incredible movement of the spirit that brought us all together because it's unusual that I would be with Mom and Frida and Kate in Pennsylvania so close to New York," Jerry Berrigan said in a telephone interview with NCR April 30.

"Our plan was to be there for the weekend, and we got the report this morning that [Dan] possibly would not survive the night, and we looked at each other and said, 'Let's go.' And we were waiting to get on the George Washington Bridge when the news came that he has passed."

Jerry, who lives with his family in a Catholic Worker community in Kalamazoo, Mich., said the family "experienced incredible grace" while spending Saturday afternoon "sitting with Dan's body after he had died. And we had about five hours in his room with him there."

With other friends also present, McAlister and her three children gathered to remember Dan.

"We shared stories and cried and laughed and looked at photographs, and he was with us for this long time, this whole afternoon," Jerry said. "And I don't think I'll ever forget that. It seems to me that one of the things he stressed above all in his life and in his work was the dignity of the human person, and the absolute centrality of each human individual in any kind of political calculation or any kind of move. The human being comes first. And, in his last hours he was honored in that way by his community of friends, and then we were honored to reflect on the sacredness of his human life with him still there, and it was wonderful."

A statement released by the family, said in part: "[W]e are so aware of all he did and all he was and all he created in almost 95 years of life lived with enthusiasm, commitment, seriousness, and almost holy humor. We talked this afternoon of Dan Berrigan's uncanny sense of ceremony and ritual, his deep appreciation of the feminine, and his ability to be in the right place at the right time. He was not strategic, he was not opportunistic, but he understood solidarity — the power of showing up for people and struggles and communities.

"We reflect back on his long life and we are in awe of the depth and breadth of his commitment to peace and justice -- from the Palestinians' struggle for land and recognition and justice; to the gay community's fight for health care, equal rights and humanity; to the fractured and polluted earth that is crying out for nuclear disarmament; to a deep commitment to the imprisoned, the poor, the homeless, the ill and infirm.

"We are aware that no one person can pick up this heavy burden, but that there is enough work for each and every one of us. We can all move forward Dan Berrigan's work."

Turning swords into plowshares

Daniel J. Berrigan was born May 9, 1921, in Virginia, Minn., the fifth of six boys to Thomas and Frieda Berrigan. After his family moved to Syracuse, N.Y., where the sons attended Catholic schools, Berrigan entered the Jesuit novitiate at St. Andrew-on-the-Hudson, N.Y., in August 1939. He graduated in 1946 and entered the Jesuit's Woodstock College in Baltimore, graduating from there in 1952, the same year he was ordained.

After a year of studying and ministering in France, where he met some worker-priests who gave him, he wrote, "a practical vision of the church as she should be," he was assigned to teach theology and French at the Jesuits' Brooklyn Preparatory School.

In 1957, Berrigan was appointed professor of New Testament studies at Le Moyne College in Syracuse, and he won the Lamont Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets for his book of poems, Time Without Number. He would go on to publish more than 50 books of poetry, essays, journals and scripture commentaries.

However, it was his anti-war work for which Berrigan gained his most notoriety, spending approximately two years of his life in jail and prison.

He joined other prominent religious figures like Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, the Rev. Richard John Neuhaus, then a Lutheran pastor, and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to found Clergy and Laity Concerned About Vietnam.* In February 1968, he traveled with historian Howard Zinn to North Vietnam and returned with three American prisoners of war who were released as a goodwill gesture.

Rabbi Michael Lerner, met Berrigan when Lerner was the chair of Students for a Democratic Society at the University of California Berkeley. Lerner recalled that meeting in a statement issued May 1. "He told me," Lerner wrote, "that he had been inspired by the civil disobedience and militant demonstrations that were sweeping the country in 1966-68 … Over the course of the ensuing 48 years I was inspired by his activism."

"Heschel told me how very important Dan was for him -- particularly in the dark days after [President Richard] Nixon had been elected and escalated the bombings in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.

"Those of us who were activists were particularly heartened by [Berrigan's] willingness to publicly challenge the chicken-heartedness and moral obtuseness of religious leaders in the Catholic, Protestant and Jewish world who privately understood that the Vietnam war was immoral but who would not publicly condemn it and instead condemned the nonviolent activism of the anti-war movement."

Berrigan will forever be mentioned in the same breath as his late brother, Philip, who died of cancer Dec. 6, 2002. The brothers were constant companions in crime, arrested together at the Select Services System office in Catonsville, Md., May 17, 1968, for using homemade napalm to burn draft files. A dozen years later, Sept. 8, 1980, while spearheading the faith-based opposition to the nuclear arms race, the Berrigan brothers and six others, brazenly forced their way into a General Electric armaments factory in King of Prussia, Pa., and pounded on two Mark 12A nuclear missile nose cones with simple carpenters hammers to, as they described it, disarm the weapons. Inspired by a passage from the Isaiah, they symbolically sought to turn swords into plowshares.

Scores of activists, mostly Catholics, followed the Berrigans' lead, participating in similar draft board raids and Plowshares actions.

Addressing many issues, during a life of activism

Former U.S. Attorney General, Ramsey Clark, 88, who maintained a close association with the Berrigans and sometimes represented Philip in court, said he was fortunate to have known Dan for many years.

"I've not known a more wonderful human being, kind and pious and good," Clark said, "and he lived a long and peaceful life from what I saw, always instructive. He was an inspiration to those who knew him and always optimistic, so we need more Dan Berrigans, and we'll miss him greatly."

Clark said Dan Berrigan was "a very sensitive person" and that his anti-war protests were hard on him. "I remember his testimony at one of the trials, where he said -- as frightening as it was -- he could not not do it. He was an extraordinary gentle person who did not like conflict or confrontation, but yet found a need to stand up to war.

"He and Phil were loving brothers, but so different in many ways, but they had such enormous love and respect for each other. It inspired everybody who knew them both."

Frida Berrigan, who frequently visited her uncle, bringing along her two young children, said her father and uncle had a great bond. "Dad would talk about Dan as his best friend," Frida said. "They trusted each other completely, trusted each other with their lives."

The Catonsville caper led to a three-year federal prison sentence, which was preceded with Dan Berrigan going underground, all the while playing a game of cat and mouse with the FBI. With the help of anti-war friends, Berrigan stayed on the lam for four months, giving interviews and even speaking publicly against the Vietnam War.

"I knew I would be apprehended eventually, but I wanted to draw attention for as long as possible to the Vietnam War, and to Nixon's ordering military action in Cambodia," Berrigan told America magazine in a 2009 interview.

Berrigan's life of resistance was also influenced by his personal friendships with Catholic Worker founder, Dorothy Day, who Berrigan met in the 1940s while teaching at Jesuit schools in New York City, and with Trappist monk Thomas Merton, who Berrigan met in the 1960s.

As Berrigan's anti-war activities expanded and his visibility and that of his brother, increased, Jesuit superiors ordered Berrigan to be transferred to Latin America. Berrigan left, but his so-called forced exile brought heat on the Jesuits and Berrigan returned to the United States after just four months.

Throughout his activist life, Berrigan addressed issues as they came his way. He supported and visited young IRA prisoners on hunger strikes in the Northern Ireland. He defended the reputation of an American Quaker, Norman Morrison, who shocked the nation when on Nov. 2, 1965, he immolated himself on the grounds of the Pentagon in a protest against the Vietnam War. Berrigan also protested capital punishment and U.S. military intervention.

Berrigan received criticism from the political left for his pro-life views. He was a longtime endorser of the "consistent life ethic," and he served on the advisory board of Consistent Life, an organization that describes itself as "committed to the protection of life, which is threatened in today's world by war, abortion, poverty, racism, capital punishment and euthanasia."

"I have always made it clear," Berrigan said in the America interview, "that I am against everything from war to abortion to euthanasia. I have avoided being a single-issue person."

Berrigan was arrested in 1992 protesting outside a Planned Parenthood in Rochester, N.Y.

In the 1980s, he began ministering to patients with AIDS in New York City, work he stayed with through the 1990s. Berrigan was an advisor to the film 1986 "The Mission," about 18th century Spanish Jesuits in South America, and had a cameo appearance.

Berrigan also showed a sense of humor, when during a "60 Minutes" segment that aired in the 1980s, titled "The Brothers Berrigan," he commented that getting arrested, handcuffed and placed in the paddy wagon was like a receiving a "spiritual enema -- everything's all clear at that point."

Berrigan: 'Make your story fit into the story of Jesus'

Reflecting on her brother-in-law's contributions to her family's life, McAlister told a story of a ritual Dan spearheaded at family gatherings.

"We'd have an evening together and toward the end of the evening you could sense it coming; [Dan] would throw out a question, and say a little bit about it himself, then ask each in the circle to address that question.

"And of one that I remember vividly is, 'What's giving you hope these days?' And he wanted us to elaborate on that in terms of all of the things that appeared so hopeless and then just invite and encourage people in that circle to address that. And what came out was absolutely stunning.

"We began to look on that as the highlight of visits from Dan in our household, because it made such an impact on all of us and it led to such a depth of sharing from all of us."

A few years ago, with Berrigan already in declining health, Jesuit* Luke Hansen agreed to take Berrigan to Baltimore to spend Christmas with McAlister and her family at Jonah House, a resistance community founded by McAlister and her husband.

"Sitting in the living room I encouraged Dan to move in that direction, but he didn't feel up to it, so instead I raised something and it was like continuing and like opening again a tradition, a gift that Dan had given to us as a circle of family and friends. And it was so powerful.

"Luke Hansen was profoundly moved by this evening. He said, 'I go home for Christmas and we watch football. I've never been part of circle where this kind of a sharing is done in a family.' And I said, 'This is Dan's gift. This is what he has brought us to all of my life with him, and we're just trying to continue this thing that's one aspect of life with him that has been particularly precious.'"

McAlister continued: "You know you can talk about all of the public witness [that Berrigan did], but that public witness comes out of that kind of soul-searching in a circle of community and family, that strengthens people and clarifies things for people to be able to get up and get out and be public. And when I think of Dan, and when I think of all the gifts he has given us, this is perhaps the most precious to me."

Fr. John Dear,* a former Jesuit who lived with Berrigan and edited his writings, called Berrigan, "My greatest friend and teacher, one of the greatest peacemakers, a great saint and a prophet."

Dear said that Berrigan "changed the history of the Catholic church, not just in the United States, but in the whole world. He influenced millions, perhaps hundreds of millions of people. I consider Dan to be in the same league as Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Dorothy Day and his brother Phil."

Dear said he once asked Berrigan, " 'What's the point of all this, Dan?' and he said to me, 'All you have to do is to make your story fit into the story of Jesus.' And I thought that was the most profound answer; I still do. He could have said you do the work to end all war, but he told me to make sure I fit my life story into Jesus's story. Now I think that's what he did."

In a reflection about Berrigan, pacifist David McReynolds, a longtime staff person at the War Resister's League in New York City, wrote April 30: "There will be great sadness, but also joy at a life so well and truly lived, as an act of poetry in a world so bloody and violent."

Frida remembers that for her and her siblings, who did not have grandparents, Berrigan filled a void. Dan was "a kind uncle who is just so different," Frida said. "He lived in New York City. It was so great to continue to go to that same space where Dan lived on 98th Street, continuously seeing him and visiting him. Just being in his space was so meaningful.

"He would write on the wall, notes, sayings, poetry with magic marker. It was unlike any other place we would go. He aged, but he never did really change. Life is always in flux, things continually change, but he was a constant."

As a child, Frida said she remembers walking down the street with Berrigan on New York's Upper Westside -- "jaunty happy walks. He really observed things and people, interacted with a lot of people. Here is a guy who really enjoyed life, and enjoyed people and was celebrating God's love.

"To have his full attention as a kid was a real gift. I had an audience with him. He would give us his full attention. I got his full attention. It was just such a pleasurable experience for all of us. He appreciated it."

On April 29 as she was on her way to her family weekend, Frida stopped to see her uncle for what was the last time. Reflecting on that visit shortly afterward, Frida wrote on her last previous visit, Berrigan "laughed at the kids' antics and was almost jolly by comparison."

April 29 was different.

"I went into his room, happy -- for once -- that I did not have small energetic children in tow. He did not really register me being there at all," Frida wrote. "I tried to talk the whole time: reading from To Dwell in Peace, [Berrigan's autobiography] which was almost impudent in its Dan-ness, full of turns of phrase and unpronounceable words. …

"Sian, his aide, came in to check on him and try to gently rouse him, but he would not wake. I showed her and Sofina, the nurse, pictures of Dan at [ages] 7 and 10. … It was sweet but sad. Hard to watch his labored breathing -- hard to be there, harder to leave."

Frida planned to visit her uncle again on Sunday, May 1, after the family reunion. He died Saturday.

*An earlier version of this story included an incorrect name for Clergy and Laity Concerned About Vietnam, and referred to Jesuit Luke Hansen as Jesuit Fr.; John Dear's religious title has been added.

[Patrick O’Neill is a longtime NCR contributor.]