(Unsplash/Zbynek Vurival)

In Loaded, her "disarming history of the Second Amendment," Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz makes an argument I found hard to dispute: "In America, the gun is God."

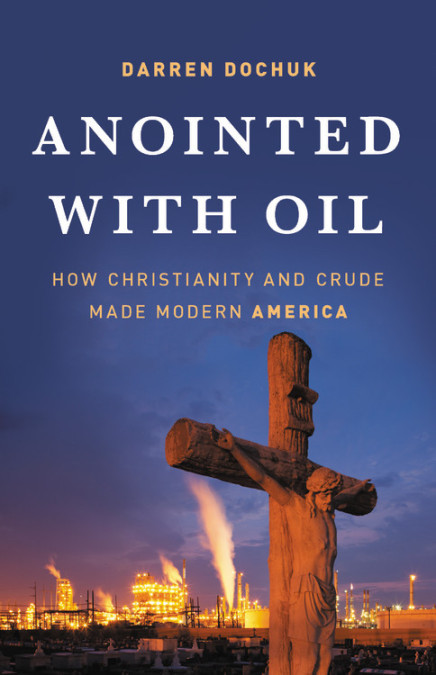

But after reading Darren Dochuk's Anointed with Oil, I had to reconsider my conclusion: Perhaps in America, it's oil that's God, or at the very least, it's oil that is the unambiguous blessing with which God has anointed America as the most "exceptional" sovereign power on Earth.

Dochuk traces the story of oil from its 1859 discovery in western Pennsylvania through further massive discoveries in Canada, southern California and Texas during and after the Civil War, and eventually, to the shift to Latin American and Middle Eastern oil in the 20th century and the fracked oil boom of the 21st century. Running through it all is the power struggle between the eastern "big oil" companies led by the Rockefellers of Standard Oil, and the smaller, more risk-taking independent oilers of the Southwest. And shaping that struggle, and virtually the entire history of U.S. oil, were two competing theological visions: East Coast liberal Protestantism and the evangelicalism of small-town Protestants in the Southwest.

Such an argument may seem like nothing more than another take on the classic division between liberal and conservative American Protestants. Dochuk's study is a good deal more than that, however, detailing as it does the profound connections between the economic and political history of the oil industry and what Dochuk calls "the civil religion of crude" practiced by liberal oilers like the Rockefellers and the "wildcat Christianity" of independent oilmen out West.

For the first group, the Rockefellers and others, their commitment to the social gospel of global uplift and the ultimate unity of the three monotheistic faiths underpinned their outreach to oil-rich Muslim countries and their support of government regulation of oil drilling. By contrast, independent oil drillers drew on their premillennialist faith in the end times to justify the massive and unregulated exploitation of oil reserves. The gushing wells that their efforts sometimes achieved proved the imminence of Jesus' return. And even when those efforts failed, since Jesus was coming very soon, what did it matter? But for both groups, oiling was a religious enterprise and the abundance of oil bestowed on them was divine justification for U.S. imperialism.

Advertisement

For decades, scholars have discerned a connection between Protestantism and capitalism, beginning with Max Weber's groundbreaking The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism in 1905. What distinguishes Dochuk's work from theirs is that, first of all, he establishes what some have called "new religious geographies," foregrounding "space and place" in ways that highlight distinctive regional variances in practice and theology. This geographical framing underpins the differences between the austere, disciplined Calvinist work ethic of Weber's Protestantism and the impractical, sometimes out-of-control approach of premillennial "wildcat" oilers. Another distinctive aspect of Anointed with Oil is a potentially Marxist one: some reviewers argue that the material dimension of oil is so important to Dochuk's argument that he almost makes oil an agent in his history.

A final extraordinary difference between Anointed with Oil and other studies of the history of oil or of American religion is that Dochuk is a master storyteller. This is so from his opening tale of the one-armed Pattillo Higgins rejoicing at the first gusher at Spindletop, near Beaumont, Texas, in 1901, through equally amazing stories of dozens more oil actors, including John D. Rockefeller, William Eddy, son of missionaries who facilitated the triumph of Standard Oil in the Middle East, and Sarah Palin shouting "Drill, baby, drill" in 2008. Also intriguing is Dochuk's argument that a majority of early donors to the 2016 Republican presidential campaign were "latter-day wildcatters" eager to reap profits from the deregulation of the burgeoning shale oil industry. The entire book, is, in fact a thoroughly engaging narrative.

Oil from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill surrounds marshland south of Venice, Louisiana, June 19, 2010. (CNS/Reuters/Lee Celano)

Some reviewers have criticized Dochuk for not including more women in Anointed with Oil. I myself was grateful to learn much that I had not known about anti-oil journalist Ida Tarbell as well as some of the wives of oilmen who played active roles in production. Dochuk also incorporates Catholicism into his basically Protestant narrative, telling stories of Catholics like "Father Ignacy" Lukasiewicz, who in the 1890s used his oil revenues in Northwest Spain to serve the Catholic community there, and William Mulligan and Tom Barger, who defended the Aramco Catholic communities in Saudi Arabia even as they fought anti-Arabist attitudes in the U.S. in the 1970s.

I was also fascinated to learn that the extremely conservative William F. Buckley Jr. inherited his commitment to individualism and hyper-traditional Catholicism from his father who was a renowned "wildcat" but also Catholic oilman. Dochuk likewise highlights the involvement of thousands of U.S. Catholics in an organization called the Catholic Petroleum Guild, a group that celebrated its huge "Petroleum Sunday" Mass at St. Alphonsus Liguori Church in lower Manhattan in 1950 and thereafter. The story of this annual celebration effectively introduces the book's nuanced examination of the relationships between organized labor and oil management in the years after World War II. But Anointed with Oil remains, in large part, the story of two extraordinary groups of American Protestants, wildcat independent evangelicals led by the Pew family and their corporation, Sun Oil, and liberal Protestants, led by the Rockefellers of Standard Oil.

Some may be deterred from reading Anointed with Oil because of its length: 560 pages, not counting the endnotes. But as I already indicated, Dochuk is a brilliant narrator; one reviewer claimed that the book is more like a Russian novel than a history. I myself could hardly put it down.

And even if you aren't particularly interested in oil, or in American Protestantism, please be aware that Dochuk manages to narrate virtually the entire history of the United States, from the Civil War to the election of President Donald Trump, through the lens of these two overlapping trajectories, oil and American religion. If you're anything like me, you'll be astounded by all that you learn from this splendid book.

[Marian Ronan is research professor of Catholic studies at New York Theological Seminary, a Black, Latinx and Asian theological school on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City.]