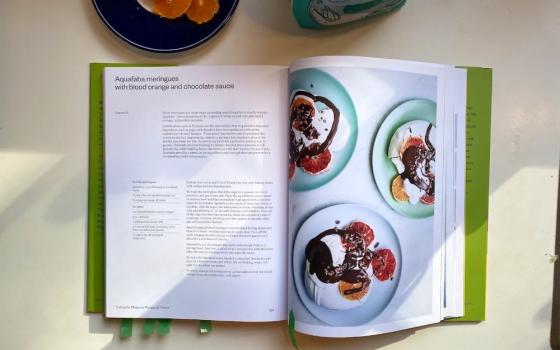

The Rev. Michael Malcom addresses the "Resilence for Congregations" conference at Lovers Lane United Methodist Church on July 15, 2023. (UM Insight/Cynthia B. Astle)

Editor's Note: This story originally appeared in United Methodist Insight and is part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.

The familiar adage that "everybody talks about the weather, but nobody does anything about it"* got a new interpretation recently for faith-based climate activists: It's time to turn our conversations about this summer's extreme weather into action to save ourselves and planet Earth from death.

That re-interpretation — and its urgency — came from two keynote speakers July 15-16 at a conference "Resilience for Congregations," held at Lovers Lane United Methodist Church and co-sponsored by Texas Interfaith Power & Light and the City of Dallas Office of Environmental Quality and Sustainability. The conference included five workshops on urban agriculture, environmental justice, water, climate migration and energy.

Texas Interfaith Power & Light is affiliated with Texas IMPACT, an interfaith public policy education and advocacy organization. Its membership includes all five United Methodist annual conferences in Texas, United Women in Faith and the Methodist Federation for Social Action.

Churches need to be advocating for a three-pronged approach to the climate crisis that has so intensified this summer's weather, said the Rev. Michael Malcom, executive director of both The People's Justice Council, a non-profit organization focused on theology and climate justice that he founded in 2017, and Alabama Interfaith Power & Light.

Advertisement

It was ironic that the conference took place while Texas and much of the Southwest were broiling in excessive heat, said Malcom, a United Church of Christ minister from Birmingham, Alabama.

Even though the conference's theme was "Resilience for Congregations," this summer's extreme weather events — from excessive rainfall and floods in the U.S. Northeast through scorching heat in the Mediterranean and southern Asia regions — are showing the world that the climate crisis has overtaken humanity, Malcom said.

"I'm sitting in a United Methodist church talking to church folks and I'm wondering why we aren’t talking about this heat?" he asked the gathering. "We know that these situations are happening. In essence we're just talking when we know we can do something about it."

Malcom zeroed in on different understandings of "resilience" between white, affluent communities and low-income communities, often neighborhoods of Black, Indigenous and other people of color.

"Here's the problem with resiliency: we oftentimes celebrate folks' resiliency as 'they weathered the storm,'" said Malcom. "Is it really right that we celebrate someone's resilience when we can do something about it?

"When we look at resilience, especially for the Gulf South, we have been taking it and taking it and taking it," he continued. "We don't need any more 'resilience,' because that means we'll continue to suffer disasters. Instead, we need to be advocating to stop burning the fossil fuels that are causing this heat."

In the call-and-response style typical of the Black church, Malcom recommended that those attending in person and online pursue a three-pronged strategy of ecological, economic and ecumenical restoration.

"God created the earth and everything in it, people and planet," he said. "Leave God's ecology alone and it will take care of itself. But that's our problem: we can't leave well enough alone. We have to cultivate nature and let it take its course."

Susan Alvarez, assistant director of the City of Dallas' Office of Environmental Quality and Sustainability, talks about the importance of citizen input to the city's climate plan at the "Resilience for Congregations" conference July 15 at Lovers Lane United Methodist Church. (UM Insight/Cynthia B. Astle)

Malcom cited biblical principles as the means toward economic restoration.

"There was a time when people had everything they needed," he said. "Did you know that Black folk have lost 90 percent of their land wealth? It's because the system was set up to take advantage of them. It has been bad because instead of leaving the edges of the fields to be gleaned by those who needed it as Boaz did (Ruth 2:7-23), we've warehoused wealth. We've got to get ourselves back to a system that ensures that none go without."

Malcom described "ecumenical restoration" as the need to "restore faith — not as society has dictated it, but the way our scriptures dictated."

"Look at the founding of the church: when fear rose, they gathered together, and Jesus came in (John 20:19-23)," he said. "Look at where we are; fear has arisen."

"How do we restore faith, not only in our churches but in each other?" Malcom asked. "We come together, those who believe, those who are called, those who understand, those who have a conscience for planet and people. We work together and use our voices to speak up against the ills that are happening in society. We use our voices to collectively speak up in prophetic utterance that this is not the way that God intended."

"We come together and fix those things that we celebrated as 'resilience,'" he said.

Susan Alvarez, a professional engineer who serves as assistant director of the Dallas Office of Environmental Quality and Sustainability, echoed Malcom's theme of faith-based advocacy's importance. She said that citizens' activism resulted in Dallas' environmental plan.

"Local governments do listen to you," Alvarez assured the gathering.

Dallas now has an Environmental Commission made up of 15 volunteers — one for each of its 14 City Council districts plus an at-large representative for the mayor — who regularly review public and private projects for compliance with Dallas' Comprehensive Environmental and Climate Action Plan (CECAP). The commission is aided by a non-voting group of professional experts in the plan's focus areas such as water, waste, transportation and air quality.

"With equity and inclusion as core values, the CECAP proposes solutions that will improve our natural environment, our educational and economic outcomes, the affordability of our housing stock, and our transportation systems," says the commission's website.

Alvarez said that Texas ranks first in billion-dollar climate disasters in the United States. Federal and state governments have allotted "lots of money for clean-up but zero for prevention." As an example, she noted that despite its most recent efforts, Dallas is facing Environmental Protection Agency fines for air quality non-attainment.

After surveying 100 ZIP codes in Dallas, Alvarez said, the city determined three primary factors in environmental sustainability:

- Access to transportation

- Affordable housing

- Food access

A surprising — and embarrassing — discovery was the effect of "batch plants" on Dallas' air quality, Alvarez said. "Batch plants" are temporary set-ups on construction sites to produce building materials such as concrete and asphalt. The survey showed that three of four batch plants surveyed for particulate pollution within a four-mile-square area belonged to City of Dallas sites, she said.

Now the environmental office consults monthly with all city departments regarding their progress on achieving CECAP's goals, Ms. Alvarez said. In addition, the environmental office works with regional governments and citizen partners such as the developers of the new municipal convention center, who have pledged the project will be "net-zero carbon emissions."

Malcom also stressed collaboration in saving "people and planet" from disaster.

"The only way we break down this system of corruption, these wages of sin, is through community and collaboration," he said. "The only way we'll get through this is together."

* The quote "everybody talks about the weather, but nobody does anything about it" is usually attributed to American author and humorist Mark Twain. In actuality, Quote Investigator traced the quote to Charles Dudley Warner, a friend of Twain's and editor of the Hartford Courant, who used the aphorism in several writings prior to its publication August 24, 1897, in the Hartford Courant, This Weather, Page 8, Hartford, Connecticut. (ProQuest Historical Newspapers)