Pope Benedict XVI admires the scenery in Lorenzago di Cadore, Italy, while on vacation in the Alps July 23, 2007. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano via Reuters)

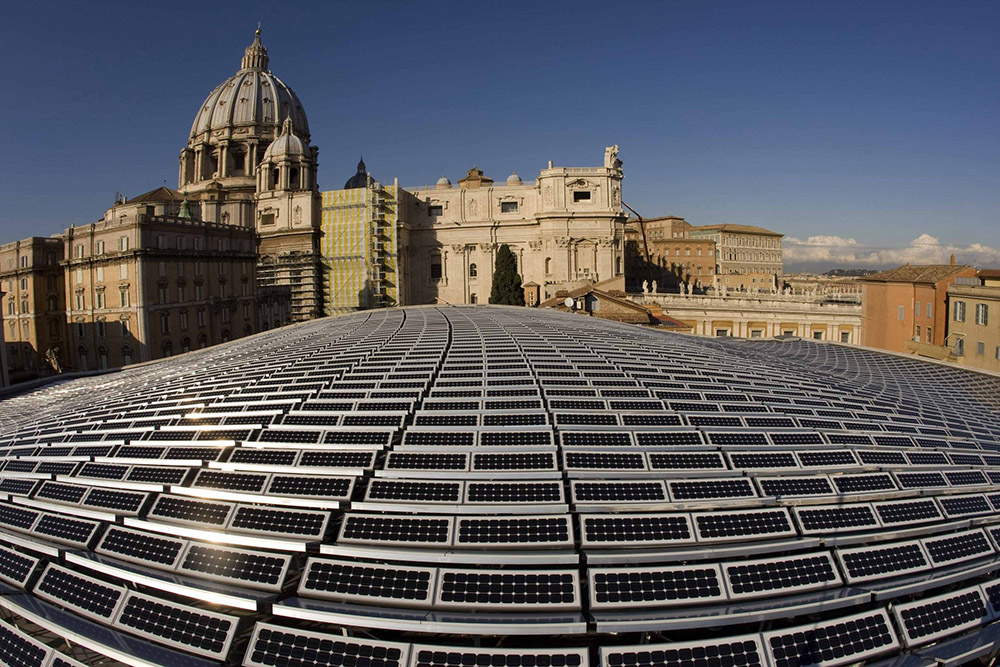

As nearly 200,000 people waited in lines outside St. Peter's Basilica this week to pay their final respects to Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, it's likely more than a few spotted the glimmer of sunlight reflecting off the roof of a nearby building.

The source, 2,400 solar panels atop the Paul VI Audience Hall, stands as a lasting symbol at the Vatican of the focus that Benedict, who died Dec. 31 at age 95, placed on environmental issues during his eight-year papacy, which ended in 2013, when he became the first pope to resign in 600 years.

The solar array and a hybrid popemobile were among visible actions taken by Benedict that led him to being dubbed "the green pope" as early as 2008, the year the panels were installed.

While important signs, theologians say an equal part of his legacy to the Catholic Church will be his writings and teachings on environmental concerns that stressed creation as a gift and how its responsible stewardship relates to other social issues and conflicts — all areas further developed by his successor, Pope Francis.

"With Benedict XVI, we had not only strong theology, very strong systematic theology, but we also had strong actions," said Jame Schaefer, professor emerita of systematic theology and ethics at Marquette University. "And I think that that paved the way for so much of what Francis has done."

Solar panels are seen from the roof of the Paul VI audience hall at the Vatican Nov. 26, 2008. (CNS/Reuters/Tony Gentile)

Vincent Miller, the Gudorf Chair in Catholic Theology and Culture at the University of Dayton, said Benedict made clear that the church had to respond to environmental threats, including climate change, that the world was witnessing at a time when global attention was ramping up.

"He saw that this was an unavoidable moral issue and he spoke about it, he taught about it and he acted on it," Miller said.

Emphasis on nature and human ecology

On April 24, 2005, in his first homily as pope, Benedict XVI laid down a marker that would help define his approach to ecological concerns.

"The external deserts in the world are growing, because the internal deserts have become so vast," he said. "Therefore, the earth's treasures no longer serve to build God's garden for all to live in, but they have been made to serve the powers of exploitation and destruction."

The connections between the ecology of nature and human ecology (a term first coined by his predecessor Pope John Paul II) would be a consistent theme for Benedict, including in his 2009 encyclical, Caritas in Veritate, where he wrote that "the deterioration of nature is closely connected to the culture which shapes human coexistence."

Both teachings were cited by Pope Francis in his encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," issued in June 2015 as the first papal teaching document devoted entirely to ecology and faith.

Benedict, known as a brilliant scholar, features prominently in Laudato Si', as Francis cites his writings nearly two dozen times.

In many ways, Benedict paved the way for ideas that Francis explored in his encyclical, Miller said, such as the idea of integral human development that Francis examines as integral ecology and that he made the name of a Vatican dicastery.

"There's just a great deal of continuity between the two, and Laudato Si' develops certain movements that Benedict makes and it develops them much more fully," Miller told EarthBeat.

Francis had ample source material from his predecessor to build from.

In his 2007 World Day of Peace message, Benedict raised the urgency around environmental destruction, warning that the race for energy resources risked destroying ecosystems, leaving people behind and "unleashing man's destructive capacities," including war and conflict.

Advertisement

Three years later, he devoted his entire peace day message to the role of the environment in avoiding conflicts, titling it "If You Want to Cultivate Peace, Protect Creation."

Among his encyclicals, Benedict spends the most attention on environmental matters in Caritas in Veritate. He frames the environment as neither above humanity nor something to recklessly exploit, but rather as "God's gift to everyone, and in our use of it we have a responsibility towards the poor, towards future generations and towards humanity as a whole."

The German pope added that "the Church has a responsibility towards creation and she must assert this responsibility in the public sphere," not only in defending earth, air and water for all but to "above all protect mankind from self-destruction."

A regular term he used was "the grammar of creation," referring to coherent patterns in nature that set out criteria for its responsible use.

Pope Benedict XVI poses for photos on a bench outside the Madonna della Salute chapel in Lorenzago di Cadore, a small town in northern Italy's mountain region July 23, 2007. Throughout the year, the pope and Vatican officials gave increased attention to environmental concerns. (CNS/Catholic Press Photo/Alessia Giuliani) (Dec. 13, 2007)

"It was [through] this grammar the world speaks to us and warns that we act in ways that are protective and caring and never abusive or degrading," said Schaefer, who in 2012 helped lead a consultation on Benedict's ecological vision with the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Catholic University of America and the Catholic Climate Covenant.

Benedict also touched on environmental themes in messages to the Vatican diplomatic corps and African ambassadors, and in a summer 2007 meeting with priests from northern Italy, whom he told, "Today, we all see that man can destroy the foundations of his existence, his earth, hence, that we can no longer simply do what we like or what seems useful and promising at the time with this earth of ours, with the reality entrusted to us.

"On the contrary, we must respect the inner laws of creation, of this earth, we must learn these laws and obey these laws if we wish to survive," Benedict said.

In November 2009, he addressed the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization in person at its Rome headquarters, where he called hunger "the most cruel and concrete sign of poverty" and stated there is a fundamental right to sufficient, healthy and nutritious food and water.

Pope Benedict XVI addresses the U.N. World Summit on Food Security Nov. 16, 2009, in Rome. (CNS/Reuters)

He added that food production methods must be considered alongside protecting the environment and with it, "the links between environmental security and the disturbing phenomenon of climate change need to be explored further," with special attention to its impacts on people most at risk.

Under his watch, the Vatican also hosted conferences on climate change, and Benedict issued regular messages to the U.N. climate conferences.

Connecting ecological issues to church tradition

Known as an excellent systematic theologian, Benedict turned to the church's tradition to speak to present-day environmental challenges, relying on his predecessor popes and heavily influenced by early church father St. Augustine and by St. Bonaventure, a 13th-century Franciscan and doctor of the church.

"There's a real sense in his work that he's not that far away from the doctrines of the church but also moving clearly into the social teaching aspect," said Franciscan Sr. Dawn Nothwehr, the Erica and Harry John Family Endowed Chair in Catholic Theological Ethics at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago and author of the forthcoming book Franciscan Writings: Hope Amid Ecological Sin and Climate Emergency.

"He's very Bonaventurian in that whole deep integration of the Trinitarian structure of all of the world and our understanding of our relationship with God and how does that fit with the human person and the Incarnation," she added.

Miller, the Dayton theologian, said that Benedict spoke about ecological concerns at greater length and on more occasions than previous popes, and did more to connect them to the depths of Catholic tradition. Frequently, Benedict tried to weave together magisterial teaching with church tradition, he added, "to show its roots, to strengthen it and to make it more robust."

Pope Benedict XVI greets the faithful as he leads his weekly general audience in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican April 11, 2007. (CNS/Reuters/Dario Pignatelli)

An example of that weaving comes in Caritas in Veritate, where Benedict writes, "The book of nature is one and indivisible: it takes in not only the environment but also life, sexuality, marriage, the family, social relations: in a word, integral human development. Our duties towards the environment are linked to our duties towards the human person, considered in himself and in relation to others."

That idea reflects how Bonaventure and Augustine spoke about creation, Miller said, and applies it to discussions about contemporary ecological concerns.

"He shows how this is deeply rooted in the tradition, that the tradition has resources to speak to this moment, and you don't have to go outside the tradition to find a way of responding to ecological concerns," Miller said.

Added Nothwehr, "He really did connect doctrinal theology with the social, ethical environmental pieces in ways that had not been done before."

Environmental actions grow church concern

Along with teaching, Benedict sought to put words to action. In his later years, he famously adopted use of a hybrid popemobile, and expressed a desire for a solar-powered model.

In 2007, a month after the Vatican announced the solar array for the Paul VI hall, news broke that the Holy See sought to become the first carbon-neutral country in Europe through an agreement to restore more than 600 acres of forest in Hungary's Bükk National Park to offset the city-state's carbon emissions.

Pope Benedict XVI waves to the crowd from inside his popemobile as he arrives for an evening prayer service at the Marian sanctuary of Etzelsbach in Germany Sept. 23, 2011, as part of a four-day visit to his homeland. (CNS/Reuters/Alex Domanski)

But the reforestation project never took root. Three years later, no trees had been planted, and the Vatican contemplated legal action against the U.S. and Hungarian companies that proposed the effort and donated the costs.

Pope Francis has since set a new goal for the Vatican to become carbon-neutral no later than 2050, with the Holy See locking in that commitment by formally joining the Paris Agreement on climate change in October 2022.

During Benedict's papacy, the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace (now the Dicastery for Integral Human Development) in 2008 issued 10 commandments of the environment, which included the international right to a safe and clean environment; the commandments were later published as a book under Benedict's name. That same year, Benedict included polluting the environment among seven new social sins. A second book, The Environment, was published in 2012.

The Pontifical Academy of Sciences during his papacy also issued a report on climate change recommending that world leaders cut carbon emissions and prepare for the impacts of a warming world.

"Benedict XVI was very clearly concerned about turning ideas about the giftedness of creation, the sacramentality of creation that speaks to us about God, into action," Schaefer said.

SolarWorld workers install solar panels on the roof of the Paul VI audience hall at the Vatican in October 2008. The solar power system was inaugurated at the Vatican Nov. 26 that year. (CNS/Catholic Press Photo/Emanuela De Meo)

Such actions helped earn Benedict the moniker of "the green pope," which was highlighted in news coverage from outlets like Newsweek and National Geographic.

Still, Benedict's focus on the environment was often overshadowed.

His pre-pope reputation as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, doctrinal watchdog for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, garnered much attention, as did investigations into women religious as pope. Benedict's academic writing style and quiet personality also were factors, as was less attention on environmental issues during his years as bishop of Rome compared to today.

"People sort of have their view and their vision of a general theme of a papacy. And I think many have forgotten that [for] Benedict XVI one of the key themes of his papacy was care for creation," said Dan Misleh, founder of Catholic Climate Covenant, which was formed during Benedict's papacy.

In November 2012, the Covenant, along with the U.S. bishops' conference and Catholic University of America sought to amplify Benedict's contributions to church teaching on environmental issues. A three-day consultation gathered several bishops and theologians. A volume of their essays and reflections was later compiled.

Schaefer, who edited the volume, said her doctoral students have been able to dive deeper into Benedict's environmental writings more so than her undergraduates, who have found easier access in the ecological messages from Francis.

Pope Francis chats with retired Pope Benedict XVI at the retired pope's home at the Mater Ecclesiae monastery at the Vatican June 30, 2015. Earlier that month, Francis had issued "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," his encyclical focused on ecology and faith. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano)

In presentations with parishes and other groups, Misleh makes a point to highlight teachings of Francis alongside Benedict XVI and John Paul II, as well as the long tradition that goes back to early church scholars and the Book of Genesis, "reminding people that this teaching has been around a long time, and if we took it seriously, we'd be in a lot better shape than we are now," he told EarthBeat.

Tomás Insua, executive director of the Laudato Si' Movement, said that both Benedict and Francis emphasize the moral act of caring for creation, limits of technology, and the responsibility the present world has to passing on a livable planet for future generations. Both also issued ecumenical statements with Patriarch Bartholomew of the Orthodox Church, aka the "green patriarch."

Still, differences are present. Where Benedict was explicit that nature was not more important than the human person, Francis has emphasized how humanity is part of creation, not separate from it.

Insua added that while Benedict suggested a sober use of energy and pursuit of alternative energy sources, Francis has been more direct in calling for countries to urgently transition from the use of fossil fuels.

Insua told EarthBeat that Catholics today can respond to Benedict's teachings "by ensuring they give full attention to caring for creation as citizens and as believers dedicated to promoting Catholic social teaching."

Rather than debate who is the "greener" pope, Schaefer said it's possible for multiple to exist. She added it's important to look beyond titles to ask why they were merited.

Added Miller, "[Francis is] taking the next step, but Benedict was starting down that path."