Sedgwick Hall at Rockhurst University, in Kansas City, Missouri, underwent a $23.5 million renovation to transform the Jesuit campus' oldest building into the new home of the St. Luke's College of Nursing and Health Sciences. The multiyear project incorporated numerous sustainability measures, making the century-old structure the most energy efficient building on campus. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

The oldest building at Rockhurst University is now the greenest on campus.

When the doors of Sedgwick Hall first opened in 1914, the four-story, stone-block structure along Troost Avenue housed the college, the high school and residence for the Society of Jesus at the Jesuit institution here in Kansas City. Essentially, it was Rockhurst.

Beginning with the fall 2022 semester, Sedgwick Hall has become home to the new St. Luke's College of Nursing and Health Sciences. Rather than tear down the century-old center of academia, university officials opted instead to undergo a multiyear $23.5 million renovation, a project not only to preserve the campus landmark as a bridge between the school's past and future, but also to repurpose the building in a sustainable way.

"It is a building that should remind us of how we are to live," said Jesuit Fr. Thomas Curran at a June dedication ceremony in one of his final acts as Rockhurst president, in front of the new Sedgwick's all-glass façade that now connects to its enduring limestone. "In sync and in harmony with the almighty, with one another and with nature."

Across the country, other Catholic institutions are finding similarly creative solutions to repair and repurpose aging infrastructure, rather than demolish and rebuild anew.

In many cases, they have grounded those plans in values espoused in Catholic teaching, including Pope Francis' 2015 encyclical, "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," which has spurred church institutions to more closely consider how their operations and facilities might better sustain ecosystems and combat climate change.

The strategies and approaches differ, but what is often a constant is a desire to preserve age-old structures that carry sentimental importance for their communities, save costs and ultimately make the best use of resources in ways that respect local environments and conserve the created world.

Jesuit Fr. Thomas Curran, center, then-president at Rockhurst University, cuts a ribbon at a ceremony dedicating the renovated Sedgwick Hall on June 3, 2022, in Kansas City, Missouri. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

Rockhurst University

The renovation of Sedgwick Hall began in 2020, or 110 years after the first stones of its foundation were laid.

At its peak, Sedgwick was the center of nearly half the education happening at Rockhurst, a small-sized Jesuit school in Kansas City. At various times, it housed a theater, a radio station and the student newspaper. But as new buildings were constructed, including Arrupe Hall in 2015 that relocated many of the College of Arts & Sciences classes from Sedgwick, the original academic hall emptied.

In 2020, the university moved to repurpose Sedgwick Hall for health sciences to meet a growing need in the region and to bring nursing students back to campus; for years, they had completed much of their studies through partnerships with nearby health systems and hospitals.

To do that, university officials considered three options: tear down and build new, keep a portion and tear down the rest, or renovate the existing structure.

The last option would go against past recommendations from engineering firms that said efforts to save the building would not be worth the costs. The western side of the building had sunk seven inches and previous efforts to shore it up had failed, said Jason Riordan, head of facilities from 2019–2022.

Advertisement

A new investigation revealed the source of sinking: nearby tree roots had grown underneath the building's footings. Nearly 100 piers were drilled deep in the bedrock to stabilize Sedgwick's west side, and an irrigation system was installed to feed the tree's roots, redirect them and prevent future damage. As Riordan put it, "The trees can grow as big as they want and the building can remain stable."

Curran, who stepped down in June after leading Rockhurst for 16 years, told EarthBeat that the building appeared to be inviting the campus to read the signs of the times: in terms of academics, a growing need in the region for health professions, and ecologically, a growing sentiment that humanity was not respecting the environment.

"Sedgwick was a great opportunity for us to meet a social need in public health and while doing that to be very, very environmentally sensitive and in harmony [with nature]," he said.

Beyond the roots beneath it, the revitalized Sedgwick has benefits for the air above, too. By forgoing demolition, the university prevented the release of an estimated 3 million pounds of carbon emissions embedded in the building's concrete.

In addition, Sedgwick's original 2-foot-thick walls combined with a new variable HVAC system make it the most energy efficient building on campus, cutting its electricity use in half. New windows and insulation prevent further energy waste. The interior uses recycled materials where possible, such as the acoustic fins (noise-shielding wall panels) in the lobby made from recycled plastic bottles, while exposed stone beams remind students and visitors of its long-lasting bones.

The interior lobby of Sedgwick Hall displays its past and present. Exposed limestone beams have stood for more than 100 years old, while new "acoustic fin" noise-shielding wall panels are made from recycled plastic bottles. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

"We were really able to pair sustainability with the history," he said.

Riordan told EarthBeat that the goal is for the 55,000 square-foot Sedgwick to be a new starting point for sustainability at Rockhurst. Already, some of the original limestone removed from the hall has been repurposed in a new Marian grotto on campus, and wood from a removed pin oak tree has been salvaged into benches, a conference table and a statue of the school mascot, Rock E. Hawk. There's also consideration of adding solar panels to Sedgwick's roof.

"This building's been here for 108 years, and the goal was to have it be here for 108 more," Riordan said.

Curran added the renovation of Sedgwick Hall invited the campus to reexamine what being a good steward means from a Catholic and Jesuit perspective.

"And we better start responding to the invitation, to what nature is saying: 'Work with us or there's consequences.' "

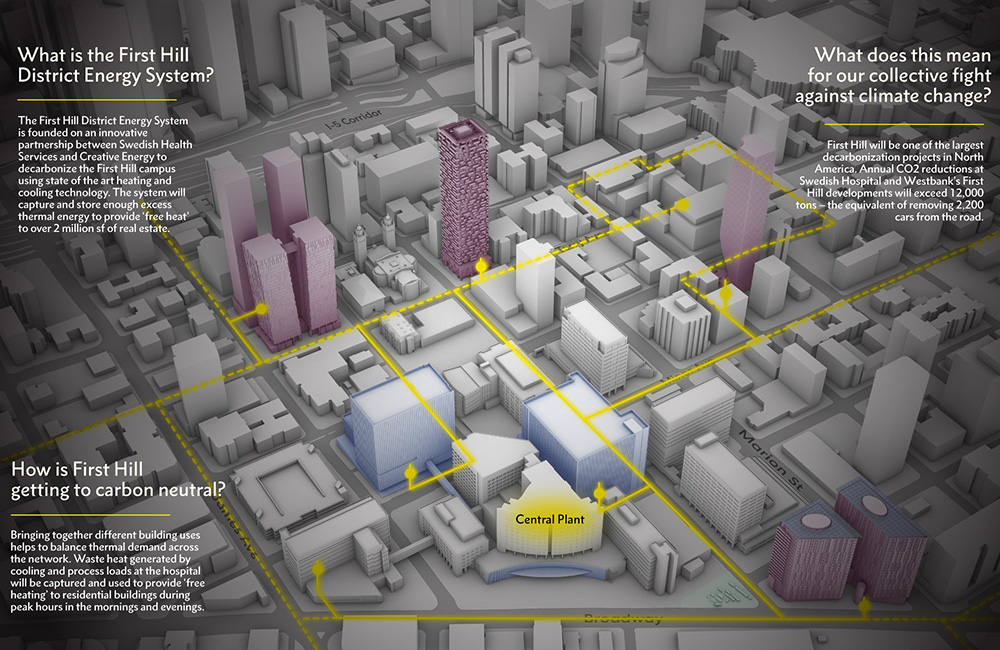

This illustration shows the district energy system proposal for Seattle's First Hill neighborhood announced March 29, 2022. (CNS illustration/First Hill Seattle, courtesy of Northwest Catholic)

Seattle Archdiocese

A new energy is forming around St. James Cathedral in Seattle's First Hill district.

Specifically, energy free of greenhouse gas emissions that are heating the planet.

In March, the Seattle Archdiocese announced plans to sell four properties it owned to Westbank, a Vancouver-based developer that is working to create a carbon-neutral energy system in the Emerald City neighborhood.

The futuristic-sounding project will provide clean energy to buildings across the First District, including the cathedral and O'Dea High School, by capturing and redirecting excess thermal energy produced by Swedish Health Services, which in March merged with Providence Health founded by the Sisters of Providence. The project, being developed with Creative Energy, aims to provide free heating to the health system, along with nearby residential buildings and the wider neighborhood, including Seattle University.

Once completed, it would make First Hill one of the largest decarbonized communities in North America, eliminating upwards of 12,000 tons of carbon emissions annually (the equivalent of taking 2,200 cars off the road), according to Westbank, which has established a similar carbon-free energy community in Vancouver.

How the Seattle Archdiocese became involved was part location, part logistics and part Laudato Si'.

The cathedral has long been a focal point in First Hill, one of the city's oldest neighborhoods. About 125 archdiocesan staff work within four nearby buildings, all of which are being sold to Westbank as part of the development deal.

"Redeveloping our real estate in a very efficient and sustainable way not only reflects our Catholic value of caring for our common home, but also provides us with resources to carry out our greater mission of bringing Christ to others," Seattle Archbishop Paul Etienne said in a March statement.

Etienne called minimizing humanity's impact on the earth "our responsibility as Catholics" and said the Westbank-led sustainability project "will ensure that the redevelopment uses green building techniques, processes and materials, while alleviating future environmental impacts with the district energy plan."

The St. James Cathedral Pastoral Outreach Center and the Paul Pigott Building, seen in the background, are among four properties the Archdiocese of Seattle and St. James Cathedral are selling to Westbank. The Vancouver, British Columbia, developer plans to create a carbon-neutral residential community in Seattle's First Hill neighborhood. Seattle Archbishop Paul Etienne announced the property sale and development plans March 29, 2022. (CNS/Northwest Catholic/Jean Parietti)

The partnership with Westbank was orchestrated by the Catholic Real Estate Initiative, a newly formed archdiocesan entity to evaluate church-owned properties, identify underutilized ones and redevelop them for new purposes. Past projects focused on providing housing for low-income families, a growing priority in Seattle where real estate prices have skyrocketed. The First Hill redevelopment plan is projected to generate $25 million toward the city's mandatory housing affordability fund, which organizations like Catholic Housing Service can tap into.

The sale of the archdiocesan properties is not yet finalized, and Westbank's plans for them remain in development, too — whether they'll be repurposed or fully redeveloped. At least one building, the 100-year-old Connolly House, will be preserved.

The new First Hill district energy system is expected to be completed by 2028.

Connolly House is among four properties the Seattle Archdiocese and St. James Cathedral announced March 29, 2022, that they are selling to Westbank, a Vancouver developer planning to create a carbon-neutral residential community on Seattle's First Hill neighborhood. (CNS/Northwest Catholic/Jean Parietti)

As the First Hill project moves forward, the Seattle Archdiocese is looking at ways to enhance sustainability within parishes, too. A new environment and risk manager is meeting with parishes and schools to "help them identify ways to incorporate Laudato Si' into their structure," said Joe Schick, the archdiocese's chief financial officer who retired in October, whether through energy-saving windows and heating systems or other steps to reduce each church's carbon footprint.

"[It's] getting the message out that the environment is important and we want to start thinking about how any renovations or remodels in parishes and schools should factor in care for creation and try to create our buildings as environmentally responsible as possible," Schick said.

Those assessments, along with the First Hill energy district, are part of the start of a larger, future Laudato Si' initiative, he added, one that is likely to include the archdiocese's participation in the Vatican's Laudato Si' Action Platform.

"We definitely are very focused on what we need to do here and what we want to do long-term. And so the environment and care for creation and sustainability are at the core of that as well," Schick said.

Fr. Jim O'Shea, provincial for the Passionists, welcomes guests to the Thomas Berry Place for the grand opening ceremony on Earth Day 2022. (Courtesy of Milton Javier Bravo)

Thomas Berry Place

There was a time when the religious superiors of Passionist Fr. Thomas Berry attempted to marginalize the 20th-century monk-scholar and his ideas about the intrinsic value of nature, humanity's destruction of the Earth, and the 14-billion-year story of the universe.

Now, they have named a retreat house in Queens after him, revamping it in ways that reflect his prophetic and outspoken calls for humans to make amends with creation.

The Thomas Berry Place held its grand opening on April 20, 2022 — Earth Day — in Jamaica, New York.

The retreat house, formerly named after Brooklyn Archbishop Thomas Malloy, underwent renovations beginning in 2021. The $6 million project has expanded the retreat center to now accommodate 50 bedrooms. A new solar panel canopy sits atop carports at the monastery and provides nearly 100% of electricity for the Immaculate Conception Monastery. The solar project was designed and completed through the Catholic Climate Covenant's Catholic Energies program.

Other new additions include an indoor hydroponics garden that will produce a variety of berries along with other fruits and vegetables to be used in meals for retreatants. The Passionists are also considering converting some of the land from manicured lawns back to natural meadows.

Together, the renovations reenvision the center, the Passionists say, as a "place of sacred hospitality" where the community can contemplate and respond to the cries of the earth and the cries of the poor — a phrase used by Berry and liberation theologians that Francis elevated in Laudato Si'.

Fr. Jim O'Shea, provincial for the Passionists, told EarthBeat that their goal was "to create a place that people understand, by just being there, what we call our charism," which is tied to the crucifixion of Christ and what Berry connected to destruction of the environment.

"Hopefully, the Place itself preaches something that is engaging to people who begin to see that things can be different or we can create different places," he said.

Thomas Berry Place in Queens serves as headquarters for Reconnect, which provides job opportunities for local young men. The young men manage Reconnect's monastery farm, which is pictured here. (Courtesy of Milton Javier Bravo)

Added Anthony Mullin, founding executive director of Thomas Berry Place, "This isn't just a remodeling of a building. It's the start of a completely new initiative, a discerning from the Passionist charism."

In addition to serving as a retreat house, Thomas Berry Place is serving as a home to women religious working on justice issues at the United Nations and provides space for meetings and conferences. The space also serves as headquarters for Hour Children, which houses formerly incarcerated women and helps them reenter society, and the Reconnect program that provides job opportunities for local young men facing difficult situations.

"The young men actually manage the urban farm, or big garden, that they have built and planted here," Mullin said.

By offering a space for prayer and reflection, social justice and second chances, the Thomas Berry Place is embodying its namesake's vision of integral human ecology and the mission Francis outlined for the church in Laudato Si' for greater care of the earth, Mullin added.

"What are the resources that we have to put at the disposition of that mission?" he asked. Responding, "In this case, one of them was this building as a resource."

Parishioners of Holy Family-St. Lawrence Parish in Essex Junction, Vermont, gather in the parish hall for Serve Your Neighbor Day in October 2018. (Stephanie Clary)

Holy Family-St. Lawrence Parish

When lightning struck the hall at Holy Family-St. Lawrence Parish, in Essex Junction, Vermont, renovating or restoring was not an option. The 19th-century timber structure burned to the ground.

"It instantly ignited with fire," parishioner Michael Dowling recalled.

That was in July 2011.

The building had served as a hub for parish activities, from meetings of the local Knights of Columbus and Catholic Daughters, to bingo and other social events. As the decision to rebuild was made, maintaining the parish center as a locus of the community was an important goal. So too was doing it in a sustainable manner.

Sustainability, along with longevity, were guiding principles, said Dowling, who serves as hall coordinator.

The new hall, which opened in 2014, features a post-and-beam frame using natural wood, simultaneously maintaining the timber aesthetic of the old building while avoiding the carbon emissions associated with producing steel. It faces south to take advantage of natural lighting during the day, while an east-facing wall offers a scenic view of Mount Mansfield. A new HVAC system and ceiling fans provide more efficient use of energy.

"We're trying to be eco-minded," Dowling said.

That's often the norm in Vermont, he added, where environmental consciousness is front of mind for many residents.

"We have to be thinking about that longevity here and protecting our Earth. But I think there's certainly a strong movement here in Vermont toward that," he told EarthBeat.

The new building now serves the Holy Family-St. Lawrence parish communities along with a third merged parish, St. Pius X. In addition, local Cub Scout troops and community organizations like Essex Eats Out, Alcoholics Anonymous and nonprofits also utilize the space. Dowling estimated that most groups renting the space are from outside the church as the number of parish activities have declined over the past several decades.

An art installation, Whale Dance, is seen overlooking Randolph, Vermont, and the Green Mountains June 16, 2021. (CNS/Vermont Catholic/Cori Fugere Urban)

But an eye toward sustainable practices didn't end with construction. In spring 2017, an intergenerational group of women initiated "green kitchen guidelines" for the hall's industrial kitchen. Groups using the hall space are now required to use the kitchen's reusable plateware and utensils, or provide their own disposable, but compostable products. Plastic-foam cups, paper plates and other non-compostable or recyclable products are barred. Separate bins for composting, recycling and trash are positioned throughout the hall.

The green kitchen initiative stemmed from a parish study of Laudato Si'.

"I felt the way the encyclical was written was a call to action," Audrey Dawson, one of the originators of the green kitchen committee, told Vermont Catholic, the diocesan publication, at the time of its start. Her experiences at World Youth Day in Brazil in 2013, the first for Pope Francis, opened her eyes to the impacts of pollution on economically challenged people.

"Seeing how interconnected environmental and economic issues were for these people piqued my interest to do something in my own church community," she told Vermont Catholic.

Perhaps the sustainable feature of the new hall of greatest interest to the parish is its proximity, now located farther from Holy Family Church, itself constructed in 1893.

As Dowling put it, "So that should [the hall] catch on fire again — if lightning does in fact strike twice — then it hopefully won't take the church with it."

[Milton Javier Bravo contributed to this story.]