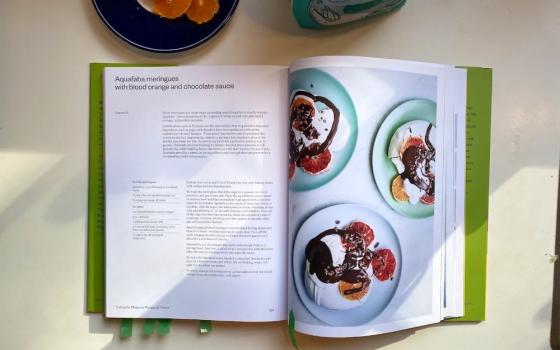

In India's Thar Desert, small patches of forested landscape, known as orans, are considered sacred by local communities. Plans for solar development in the area threaten the orans, which have stood for hundreds of years. (Wikimedia Commons/Khalid Majeed Afridi)

Editor's note: This story originally appeared on AGU's Eos Magazine. It is republished here as part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalistic collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.

India has an ambitious target to generate 175 gigawatts of renewable energy by 2022. Lands chosen to generate the solar component of this energy goal include the Thar Desert, a huge ecosystem in northwest India mostly located in the state of Rajasthan.

Like many deserts, the Thar is often inaccurately described as "barren" or a "wasteland" instead of a productive ecosystem with thriving niches. Among other habitats, the Thar is dotted by orans, small patches of forested landscape.

For generations, local communities have considered orans sacred groves. Orans usually host temples with local deities and are also used as grazing lands, especially during the dry months between April and June and October and December.

Earlier this summer, demolition and construction equipment was brought in to cut down trees and make way for high-tension power transmission lines in a 9,634-hectare (23,806 acres) oran in a village called Sanwtha.

There are about eight villages around the oran, each with about 50–60 people, most of whom are herders. Locals have honored the oran as sacred for at least 600 years, and during this time, they have never cut any trees or tilled the land, only allowing their herds to graze. Today, an estimated 5,000 camels and more than 200,000 goats and sheep depend on the oran for grazing.

The power lines will connect to a 700-megawatt grid service station (GSS) located just a few meters outside the oran. The station already supports windmills installed in the area, explained Parth Jagani of the Ecology, Rural Development and Sustainability (ERDS) Foundation, a Rajasthan-based conservation organization.

The GSS will also support a large solar park. Although the park will be installed outside the oran, many residents worry it is still a threat.

"Even today they are cutting down trees and plants to install power lines in a few areas inside the oran," explained Sumer Singh, a herder from Sanwtha.

Singh noted that many such power lines crisscross the landscape and, in addition to destroying grazing grounds, there have been numerous instances when wildlife, birds in particular, have come in contact with the lines and have either died or been injured. "Just 15 days ago, a tawny eagle was electrocuted and injured," he said.

In addition to tawny eagles, the Sanwtha oran is host to a variety of wildlife, including the critically endangered great Indian bustard, of which there are only about 250 mature adults left in the world. Numerous migratory birds, including Siberian species that fly over during winter, are frequent visitors. The habitat is also home to the chinkara (Indian gazelle), desert fox, and nilgai (huge Asian antelope also known as blue bulls), among dozens of species endemic to the Thar.

When asked about the ill effects of high-power transmission lines on local wildlife, Tulasa Ram, a tehsildar (administrative official) of the Fategarh area that comprises Sanwtha, dismissed such concerns. He said "[power] lines have to be placed if electricity has to be produced … accidents happen on roads too … animals die but we cannot stop developmental work because of this."

Advertisement

Power Struggle

Currently, Bhadla Solar Park near Jodhpur, Rajasthan, is India's largest solar facility, with an installed capacity of 2.25 gigawatts. "What will come up near [the Sanwtha oran] is very likely bigger than [Bhadla]," explained Sumit Dookia, a wildlife biologist at Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University in New Delhi and scientific adviser to the ERDS Foundation.

The dilemma faced by Indian villages over solar power echoes a similar conflict over wind power. Dookia noted that when the state government started building wind energy parks back in 2001, villagers started demanding that their lands be saved.

Jagani agreed. "In 2004, about 23,000 bighas [3,690 hectares, or 9,118 acres] of the land were recorded as orans in governmental records," he said. When the government designated land as an oran, it was recognized as a sacred space in the form of village commons.

In response to queries about how the government has the authority to indulge in work on land that belongs to the community, Ram denied claims that the community holds rights over these lands. "All of the land belongs to the government," he said.

The dilemma faced by Indian villages over solar power echoes a similar conflict over wind power.

But that statement is false. Governmental records show almost 3,700 hectares (23,000 bighas, or 9,142 acres) have, in fact, been recorded in the name of the local deity. Such an ownership is unique in the sense that "deities cannot sell the land and the local community has grazing rights and the right to respect the land," Dookia explained.

In 2018, the Supreme Court of India ordered that sacred groves of Rajasthan are to be treated as "deemed forests." Deemed forests, which account for about 1% of land in India, are tracts of land (which may include deserts and grasslands) that have not been officially recognized as federally or municipally protected forests in historic records. Designating the orans as deemed forests "is like the second layer of protection to the land," Dookia noted.

Nevertheless, power lines still cut through the orans. Additionally, nearby orans still held by the government "are being allotted to energy companies which are felling age-old trees, engaging in construction work, and damaging local ecology," Dookia said.

Villagers around the Sanwtha oran fear a similar outcome. "We want the land to be given back to us," Singh said.