Youth from Shrine of the Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Baltimore, Maryland, remove trash from the Jones Falls stream, which runs right alongside the church property. Trash from the church's parking lot and numerous surrounding paved surfaces, roads, schools and shopping plazas empties into the stream. (Photo by Bonnie Sorak/Interfaith Partners for the Chesapeake)

On a chilly fall day several weeks ago, volunteers from five Maryland congregations came together in the Cherry Hill neighborhood of Baltimore to plant 90 trees.

The planting was unique for two reasons: It drew a team of Catholics, Baptists, Presbyterians and Conservative Jews. And in the space of three hours, they managed to get all the saplings into the ground and hold an interfaith service, too.

"It was a very effective and powerful experience," said McKay Jenkins, a member of Baltimore's Brown Memorial Park Avenue Presbyterian Church and one of the volunteers at the planting. "This is not something a couple of do-gooders at one church can do."

That multiplier effect is the idea behind Interfaith Partners for the Chesapeake, a 5-year-old nonprofit organization that brought together the five congregations to plant Cherry Hill's trees. Elsewhere in the vast Chesapeake Bay watershed, which extends from western New York State into central Virginia, the group has gathered volunteers, often across the religious spectrum, to work on restoration projects, ripping up pavement, installing water gardens and, yes, planting trees.

Its work recently landed Interfaith Partners a $1 million grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. The money is intended to educate an additional 100 congregations about stormwater management and help 36 of those worship communities install green infrastructure on their properties to lessen the flow of pollutants into the bay.

Interfaith Partners already works with Protestant and Catholic churches, Jewish synagogues and Buddhist temples, mostly in Maryland, but the group hopes to expand into Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, about 50 miles above the point where the Susquehanna River, freighted with runoff from farms and paved surfaces, spills into the Chesapeake Bay.

At a time when many congregations are divided between urban and rural, liberal and conservative, rich and poor, black and white, the nonprofit, based in Annapolis, Maryland, is finding it can bring people of faith together around a common core: a shared watershed.

"We want to ignore man-made boundaries and see the God-made boundaries that unite us, like a watershed," said Jodi Rose, executive director of Interfaith Partners for the Chesapeake. "We have a responsibility to take care of these shared resources."

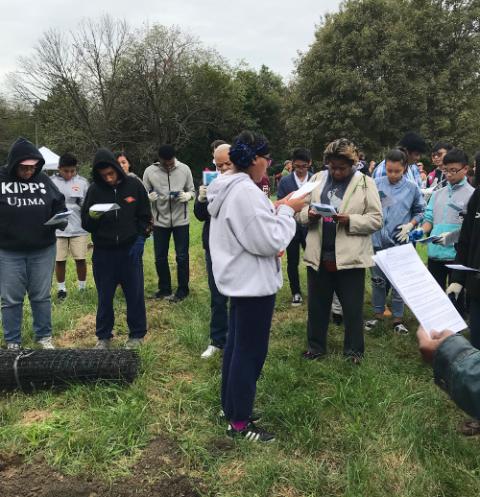

A youth leads a prayer at an Oct. 14 interfaith prayer service before youth groups from five congregations plant 90 trees in the Cherry Hill neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland. Participating congregations were Shrine of the Sacred Heart Catholic Church, St. Vincent de Paul Catholic Church, Mount Lebanon Baptist Church, Brown Memorial Park Avenue Presbyterian Church and Beth Am Synagogue. (Photo by Bonnie Sorak/Interfaith Partners for the Chesapeake)

The new grant will not actually award churches money for green projects. It will instead allow Interfaith Partners to reach more congregations and offer them more significant ways to clean up waterways. In some cases, it will also pay for technical assistance and design of those remediation projects from partner groups such as Blue Water Baltimore and Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay.

"We see our role as helping congregations graduate beyond changing lightbulbs and hosting recycling days and move into high-impact work that serves as a demonstration for the whole community," said Rose.

Memorial Episcopal Church in Baltimore, for example, expanded a tree-lined area on its property so that rainwater is now captured and filtered in tree pits rather than going into the municipal stormwater sewer system. With a $3,000 grant from Baltimore Gas and Electric, the church was able to rip up 1,200 square feet of sidewalk and enlarge the area around the trees by 36 percent.

Thirty children from area schools then completed the project by amending the soil around the trees with leaf compost, earthworms and mulch. In the process, they learned about trees and their role in a healthy ecosystem.

The church has since worked on numerous other projects, including building a pollinator microhabitat and outdoor classroom at a local public school.

"We consider ourselves a green church and we're proud of that," said Dick Williams, a church member and a consultant on sustainable building certification, who led the project. "We wish to do more."

Williams said Interfaith Partners helped educate church members on the dangers impervious surfaces pose for the health of waterways. It also identified potential grantors to fund the proposed work.

That kind of assistance is key, said Rosemary Flickinger, volunteer garden manager for the Kadampa Meditation Center of Maryland.

Advertisement

When the Kadampa Center moved into its new building in northern Baltimore, it had recurring flooding in its parking lot after heavy rainstorms. The temple's leadership asked Flickinger to look into possible grants to do some remediation work.

"I discovered the Chesapeake Bay Trust had a grant that was available," said Flickinger. "But I'd never written a grant before. Interfaith Partners said: 'Don't worry about it. We'll help you.' "

The temple was able to secure a $30,000 grant (with a matching $30,000 in labor) to install three rain gardens. It has since added a rooftop cistern.

Interfaith Partners is now expanding its work in rural areas, such as Wicomico County on the eastern shore of Maryland.

The region, which is heavily agricultural and vulnerable to sea rise, recently formed a core group of a dozen religious congregations, including a mosque and a Baha'i temple, to work together on environmental projects. The Wicomico Interfaith Partners for Creation Stewardship has not only planted trees and cleaned up streams, its members have built community and camaraderie.

"Folks here see the importance of taking care of the land," said Matthew Heim, a volunteer organizer for the group. "That brings a lot of people to the table."

A Baltimore Gas and Electric crewman works with elementary and middle school students from the Bolton Hill area on a community greening project around Memorial Episcopal Church on Oct. 6, 2017, in Baltimore. The project expanded tree pits and improved stormwater mitigation practices. (Photo courtesy of Dick Williams)

The challenge now is to get megachurches with huge facilities and massive parking lots on board. "We're going to continue trying," said Heim.

Interfaith Partners has also forged a good working relationship with the city of Baltimore.

"We're limited in what we can do on private property," said Mark Cameron, who works on watershed planning and partnerships in Baltimore's Department of Public Works. "That's where IPC comes in. They're helpful in expanding the reach of what we're able to do and helping people understand it's not just the city's role to have cleaner neighborhoods, cleaner waterways and a cleaner bay."

Jenkins, the church volunteer who helped plant the trees last month, is also a professor of environmental humanities at the University of Delaware. But he said he's especially proud of the way his Presbyterian church has stepped up its game on the environment, in part because of Interfaith Partners, where he now serves on the board.

"Environmental activity is part of our MO," said Jenkins. "It's not quirky or eccentric or on the periphery. It's central to what we do."