Firefighters in Detroit, Oregon, assess wildfire damage to a church Sept. 14, 2020, in the aftermath of the Beachie Creek Fire. (CNS/Reuters/Shannon Stapleton)

From national economies to personal lives, the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 placed much of the world on pause. But one thing didn't stop: climate change.

While global emissions declined an estimated 7% because of halts in activity that were related to COVID-19 restrictions, climate scientists project 2020 will rank among the two hottest years on record, and possibly top the list. Add to that a historic hurricane season in the Atlantic, Arctic sea ice hitting a near-record low and record-breaking wildfires in Australia, California and Siberia.

The 2020 pause delayed attention to climate at the start of a critical decade, during which global greenhouse gas emissions must be halved to keep pace toward net-zero emissions by 2050 in order to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

In many ways, 2021 will be about making up for lost ground.

Within the U.S., that means a new president — and new Democratic majority in Congress — making up for four years of environmental deregulation and deemphasis on addressing the growing climate crisis under President Donald Trump.

At the international level, it means making up for missed deadlines after COP 26, the United Nations climate summit now scheduled for November 2021, was delayed by the pandemic.

And within the Catholic Church, it means making up momentum to begin a wider, deeper implementation of Pope Francis' 2015 encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home."

Promise of a platform

For the Catholic Church, the first five months of 2021 will continue the Laudato Si' special anniversary year, which the Vatican declared in May 2020 as part of activities marking five years since the socio-environmental document's publication. That the Laudato Si' Year bridges two calendar years was itself a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The year is part of an effort to bring about the "ecological conversion" Francis says is necessary to address this decade's urgent challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss and the need to create a more just and sustainable post-COVID-19 world.

Pope Francis meets with a group of clergy and laypeople advising the French bishops' conference on ecological policies and on promoting the teaching in his encyclical Laudato Si' Sept. 3, 2020, in the library of the Apostolic Palace at the Vatican. (CNS/Vatican Media)

As part of the continuing Laudato Si' Year, the Vatican plans to hold its third roundtable at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. It has also explored a possible spring gathering of religious leaders. The special year is set to conclude in May with a conference, possibly an encyclical-inspired global musical performance and the first Laudato Si' awards.

The end of the Laudato Si' Year will also mark the beginning of the Laudato Si' Action Platform.

The platform, set to launch on May 24, is a project of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, which has invited Catholic institutions of all types and sizes to commit to a seven-year journey to become "totally sustainable in the spirit of the integral ecology of Laudato Si'."

The platform's seven sets of Laudato Si' goals include steps like achieving carbon neutrality, defending all life, using less plastic and eating less meat, and divesting from fossil fuels while reinvesting in renewable energy.

Since the action platform was announced last May, the dicastery has consulted a wide cross-section of the church on how best to build it. The work has focused on finalizing the seven types of church institutions that will participate and defining the benchmarks for each group of goals to be achieved at various points during the seven years.

A steering board working with the dicastery on the platform includes Caritas Internationalis, the International Union of Superiors General, CIDSE, Global Catholic Climate Movement and the Society of Jesus. Input also comes from Catholic organizations at more local levels, such as Living Laudato Si' Philippines and Mercy Health in Australia.

In the U.S., the Catholic Climate Covenant serves as the hub for the Laudato Si' Action Platform. As the Vatican works out the program's details, the Covenant has formed its own working group to prepare to implement the platform in the country.

"We are trying to build the architecture to make this happen," said Jose Aguto, Covenant associate director.

Aguto encouraged Catholics interested in participating in the action platform to contact the Covenant. Asked what kind of impact the action platform could make, he replied, "Transformational."

Catholic schools in the U.S., for example, could adapt the platform's global targets through existing programs of the National Catholic Educational Association and the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities. "When you have the Vatican blessing and NCEA's already got the plane on the ground, you got to just fill that up with passengers," Aguto told EarthBeat.

"It is the proverbial pebble on top of the mountain to get the big old snowball going."

From pledges to policy

As in the church, the sense of renewed momentum on climate change is also present in U.S. politics.

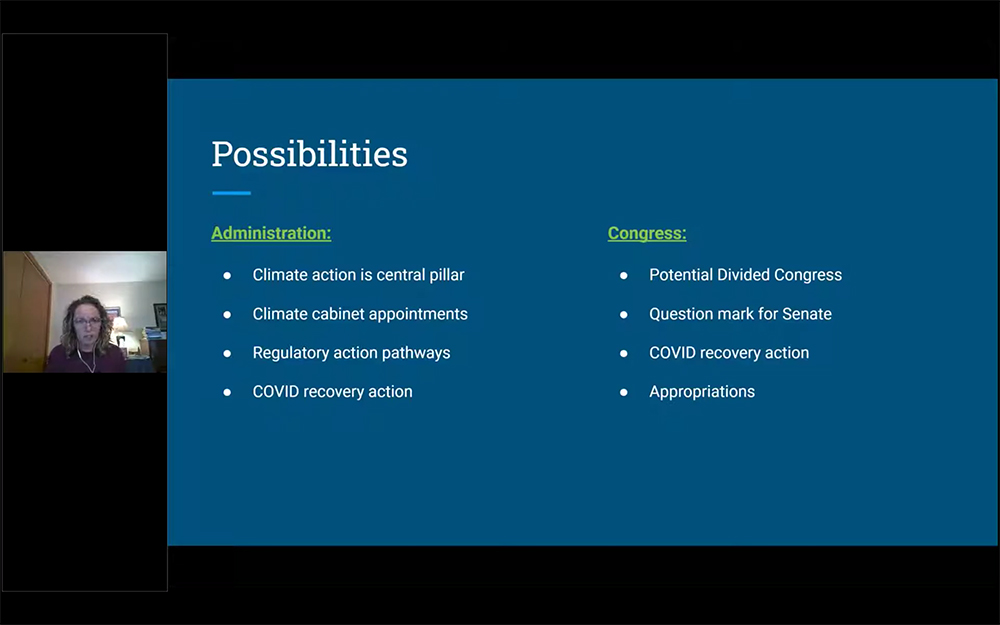

The election of Joe Biden as president is expected to bring an environmental about-face from the federal government after four years of regulatory rollbacks and promotion of oil, coal and gas under the Trump administration. How drastic the shift will be will partly depend on what can move through Congress — aided by the Democratic victories in the twin runoffs Jan. 5 for Georgia's two Senate seats.

Advertisement

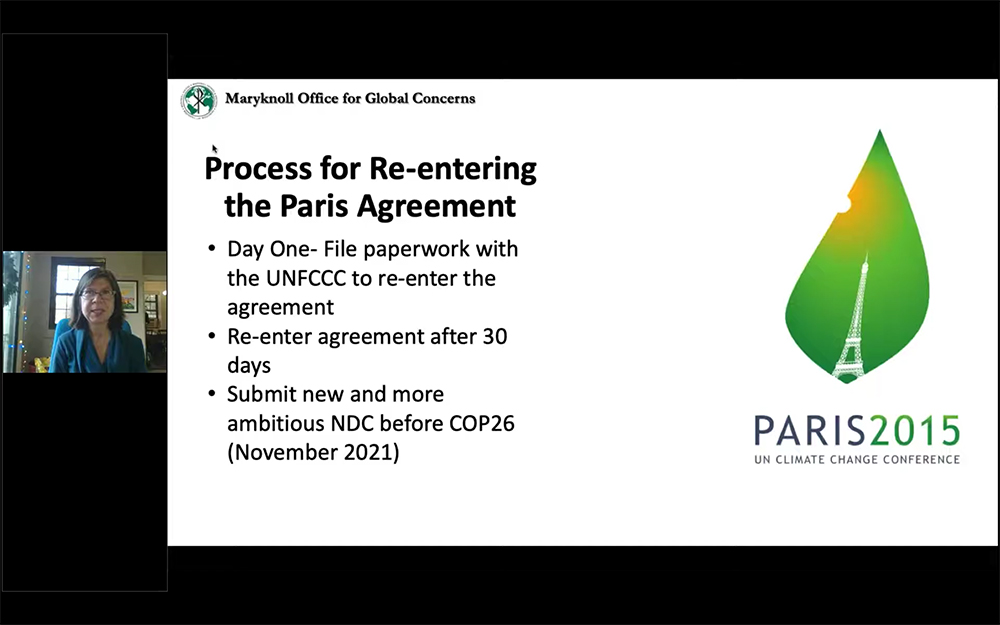

Biden has made the climate crisis one of four priorities once he enters the White House Jan. 20. On that day, he has said, he will advise the U.N. that the U.S. will return to the Paris Agreement on climate change, a decision that would take effect 30 days later.

That's the easy part, said Chloe Noël, project coordinator on faith, economy and ecology for the Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns.

"But then we need to do the hard work of putting together an ambitious pledge for reducing our greenhouse gas emissions" ahead of COP 26, set for November in Glasgow, Scotland, she said during a Dec. 10 webinar on climate policy in 2021, hosted by the Catholic Climate Covenant.

The basis of that pledge is likely to be Biden's climate plan — spending $2 trillion over four years to decarbonize the U.S. power sector by 2035 and shift the economy to 100% clean energy and net-zero emissions no later than 2050, creating tens of millions of jobs and revamping the nation's infrastructure along the way.

While Biden has made clear through Cabinet picks his intention for a full press on climate from the federal government, "legislation has to happen in Congress," said Rebecca Eastwood, advocacy program manager for the Columban Center for Advocacy and Outreach.

That effort to convert climate plans to policy got a boost this week from the Peach State.

The assault on the U.S. Capitol by Trump-supporting insurrectionists partly obscured the victories by the Rev. Rafael Warnock and Jon Ossoff, both Democrats, in the Georgia Senate runoffs. Their wins mean Democrats will hold slight majorities in both the Senate — now split 50-50, with Vice President Kamala Harris positioned as tiebreaker — and the U.S. House of Representatives.

Eastwood told EarthBeat on Jan. 7 that Democratic control of the Senate makes it more likely that Biden's nominees will be confirmed and that climate and environmental justice will play a central role in stimulus or infrastructure packages passed by Congress.

"Consensus will still be difficult, but the legislative window hasn’t been this open in a while," she said.

Rebecca Eastwood, advocacy program manager for the Columban Center for Advocacy and Outreach, speaks during a Dec. 10 webinar on climate policy in 2021, hosted by the Catholic Climate Covenant. (NCR screenshot/YouTube/Catholic Climate Covenant)

During the Covenant webinar, Meghan Goodwin, associate director of government relations for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, said the conference is "actively communicating" with the incoming Biden administration's transition team and appointees. She added that a virtual forum that the bishops' conference held with the co-chairs of the bipartisan Senate Climate Solutions Caucus "was a great success" and "laid the groundwork" for continued dialogue on climate solutions.

Goodwin outlined a long list of environmental priorities shared by the bishops and Biden. At the top was environmental justice, an issue she called "a top priority of the bishops" and one that the president-elect emphasized throughout his campaign.

Other common concerns include rejoining the Paris Agreement with bolder emissions-reduction goals, reversing Trump's environmental deregulation, addressing climate-related causes of migration, and greater integration of climate policy into infrastructure bills and foreign policy.

On the latter, Goodwin raised the possibility of reworking "debt-for-nature" swaps, a concept Biden backed as chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, in which a country is offered foreign debt relief in exchange for climate-related actions, such as conserving tropical forests.

"We expect the Biden administration to be receptive to these asks, and we look forward to working together with them toward these ends," she said.

With the possibility of divided government in Washington eliminated by the Georgia Senate races, bills with bipartisan support stand a greater chance of not only passing, but enduring, speakers at the webinar said.

Faith groups lobbying in D.C. see possibilities for attaching climate measures to legislation through the budget appropriations process and future COVID-19 recovery packages. That could advance legislation to support communities exposed to pollution, conserve public lands and oceans, protect indigenous communities and land defenders, and provide financing through accounts like the Green Climate Fund to help developing countries respond to climate change.

Those goals were among the environmental recommendations listed in a letter to the Biden administration and Congress issued by 26 religious organizations, among them Interfaith Power & Light, the Episcopal Church, the National Baptist Convention and a half-dozen Catholic groups. They lent support to specific legislation like the 100% Clean Economy Act in the House and the Environmental Justice for All Act and Environmental Justice Legacy Pollution Cleanup Act in both chambers

Chloe Noël, project coordinator on faith, economy and ecology for the Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns, speaks during the Dec. 10 webinar hosted by the Catholic Climate Covenant. (NCR screenshot/YouTube/Catholic Climate Covenant)

Noël called it a "hopeful" sign that Biden, who will become the nation's second Catholic president, has cited Laudato Si' when talking about international climate policy, and that he named John Kerry — a fellow Catholic who as secretary of state was involved in the Paris Agreement negotiations in 2015 — to a newly created position as special envoy on climate.

Noël expressed optimism that in reentering the Paris accord, the two Catholic leaders would apply principles not only from Laudato Si', but also from Francis' recent encyclical Fratelli Tutti, which calls for politics in service to the common good, committed to multilateralism and emphasizing long-term goals over short-term benefit.

"[They] have the opportunity to apply this new prophetic political model that Pope Francis offers us," she said.

COVID-19 recovery, climate commitments

The coronavirus pandemic afforded countries added time to prepare for the COP 26 U.N. climate summit. But in the meantime, the climate clock kept ticking.

Under the Paris Agreement, countries are expected to propose more ambitious emissions-cutting plans, referred to as nationally determined contributions, every five years. COP 26, originally set for November 2020, was the first checkpoint. Now that has been bumped to next November.

Some countries — including the European Union, the United Kingdom, China and India — presented their new pledges at a virtual summit Dec. 12, the fifth anniversary of the signing of the Paris accord. A number of the world's leading emitters have committed to net-zero emissions by midcentury, though specifics of how they will do so remain unclear. Vatican officials, including Cardinal Peter Turkson, have warned that nations have not done enough to combat climate change in the five years since the Paris Agreement was adopted.

An analysis of the early pledges, including Biden's proposals for the U.S., by the research group Climate Action Tracker indicated they would lead to an average global temperature increase of 2.1 C by the end of the century — an improvement over the 3 C of warming projected under the initial Paris pledges, but still short of the 1.5 C goal, which scientists say is critical to prevent disruption of millions of lives through rising sea levels, heat waves, disease, migration and more rampant poverty.

Global temperatures have risen 1.2 C since preindustrial times, according to the World Meterological Organization, and the increase already exceeds 1.5 C in some parts of the world.

Like climate-focused groups in the U.S., environmental activists around the globe see national COVID-19 recovery plans as critical not just for further emissions reductions, but also to fortify a global shift from fossil fuels to a clean-energy economy.

"We know that the investments that we're making now in economic stimulus priorities are going to lock us into those for the coming decades, and so we want those investments to be sustainable," said Eastwood with the Columbans, who work in 15 countries.

GreenFaith is among the groups pressing that message. The multifaith alliance is organizing a grassroots event on March 11 called "Sacred People, Sacred Earth," which it bills as the largest faith-based day of action on climate change.

In a position statement, organizers of the event say the pandemic "has revealed cruel injustices," with vulnerable and low-income communities suffering the most severe impacts. "We have seen it before. These same communities are disproportionately and catastrophically affected by the accelerating climate emergency."

"Sacred People, Sacred Earth" seeks to persuade governments to build post-pandemic economies and make climate commitments that meet the needs of all people and the planet and end "the era of conquest, extraction, and exploitation," the statement says.

Among the 10 demands organizers have outlined for governments and financial institutions are commitments and financing for 100% renewable energy for all people, including those lacking access to electricity; net-zero emissions from wealthy nations by 2030; an end of financing for fossil fuel exploration, industrial agriculture and deforestation; and respect for the legal rights of Indigenous communities.

"These actions must not perpetuate an outdated economic system that relies on fossil fuels and the destruction of the very forests, waters, oceans and soils that make life possible," a sign-on statement reads. "Instead they should accelerate renewable energy development; ensure universal access to clean water and air, affordable clean energy, and food grown with respect for the land; create jobs paying family-sustaining wages to workers in safe conditions."

One year into the 2020s, the path toward substantial emissions cuts remains long, while the time to achieve them has shortened.

Even so, Aguto of the Catholic Climate Covenant draws optimism from the sense of change within the church and governments and increasing pressure from youth and grassroots movements around the globe.

"We've got some serious momentum versus what we were experiencing previously," he said.