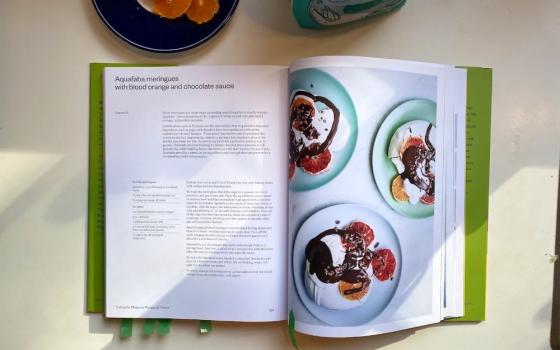

A boy looks at his mother as she picks coffee beans on a farm in Alotenango, a rural community in Guatemala hit by the coffee rust disease La Roya in 2013. (Newscom/EFE/Saul Martinez)

Editor's note: This story is part of NCR's partnership with Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story.

Many Central Americans arriving at the U.S. southern border are escaping a toxic mix of gang violence, poverty and corruption. But for record numbers of Guatemalans deciding to emigrate more recently, the root cause appears to be climate change and the devastating effect it has had on that country's coffee crop.

The Guatemalan coffee industry is the country's largest rural employer. Farmers and agricultural laborers, once employed in the sector, now find themselves largely out of work. They are abandoning their plantations and joining the exodus north.

Experts say climate change, caused for the most part by pollution from the developed North, is disrupting formerly predictable rain cycles. Complicating attempts to revitalize the industry were a recent drop in global coffee prices and a pervasive disease, exacerbated by shifting climate patterns, that killed off coffee plants. Guatemala is consistently listed among the top 10 countries most vulnerable to climate change.

Data from U.S. Customs and Border Patrol shows that apprehensions along the United States' southern border peaked at 144,255 in May. Among those coming to the United States from the Northern Triangle, Guatemala tops the list, with unaccompanied minors and family units being apprehended in large numbers. Most of the migrants belong to the country's coffee-growing regions, based on deportation data.

Amancio del Valle Carrillo tried to migrate to the United States a couple of years ago. He hails from Huehuetenango — Guatemala's major coffee-growing region in the Western Highlands.

"I made the attempt [to migrate] but I was deported. With the current prices in the coffee industry, it is no longer possible, we are only surviving," he said via email.

Today, large swaths of the world's famous coffee region have been devastated by the deadly coffee rust disease — also called La Roya in Spanish. Coffee rust is a fungus that develops on the underside of the leaves. According to experts, sporadic rains and high temperatures have only helped the disease spread across the region.

A mural in the Guatemalan town of San Pedro la Laguna shows the coffee culture of the region. (Dreamstime/Markjonathank)

"La Roya affects old plants. In the past decade, we have had excess rainfall. It's the ensuing humidity that helped spread the fungus," explained Edwin Castellanos, director of the Center for the Study of Environment and Biodiversity at the University of the Valley of Guatemala.

"That's the biggest challenge with coffee right now," said Dylan Corbett, director of Hope Border Institute, a community organization working in the El Paso-Cuidad Juárez-Las Cruces region. "Coffee is important to poor countries like Guatemala, where the majority of growers are small farmers. So, it [La Roya] hits them really hard."

The spread in La Roya has also coincided with the depression in coffee prices. Earlier, small farmers would take on off-farm activity to supplement their income. Due to the drop in coffee prices, bigger farms are less likely to take on additional labor. The cost of labor in Guatemala is reportedly the highest in the region.

But the problem is not restricted to coffee alone. Drought hasn't spared staple food crops such as corn or beans. This has pushed rural communities to the edge of poverty. According to a United Nations report, those living in the Northern Triangle's "dry corridor" say that lack of food is a primary reason people leave.

Central America's dry corridor comprises parts of Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua. This region is most prone to famine, and is home to around 3.5 million people. Extreme weather phenomena like El Niño and La Niña have wreaked havoc on the livelihoods of those living there.

A Mayan family works their dry farmland in Huehuetenango Department, Guatemala, in 2016. (Dreamstime/Fotografie Sjors)

"Food insecurity is getting worse. There are more people in Guatemala going hungry and struggling for nutrients. Incidents of malnutrition are high with 50% children suffering from malnutrition. The situation affects them their entire life," said Castellanos. "The first five years are crucial for a child's development. Even if they eat well later in life, it affects their [physical] size and mental capacity."

Experts noted that the six-month rainy period in Guatemala, from May to October, has been highly disrupted. Castellanos says that the distribution of rainfall is not normal — during a single week, Guatemala experiences intense rainfall, and in the next two to three weeks, no rainfall at all.

Farmers used to plant crops based on their knowledge of seasonal weather. But the erratic weather conditions and lack of information have posed new challenges.

"There's an information gap, a lack of proper channel where someone gives out weather recommendations. Farmers are completely confused. They are walking in the dark about important questions on when to plant," said Daniel McQuillan, technical adviser for agriculture at Catholic Relief Services. If farmers miss the window of planting a crop, their food supply dwindles. And for years now, they've watched as their stocks deplete.

Burden of debt

Guatemalan farmers also find themselves saddled with debt. Many take out small loans to remove diseased coffee plants, plant new ones and harvest them. In the four years that it takes the coffee plants to produce to full capacity, low global prices hit the industry.

"The price of coffee from Guatemala peaked in 2011, and since then it has been going down. There is a high cost in the input to keep the coffee plant healthy," explained Stephanie Leutert, director of the Mexico Security Initiative at the Robert Strauss Center for International Security and Law.

Advertisement

With booming production in countries like Brazil, where the process of picking is highly mechanized, the crisis in Guatemala's coffee industry has only deepened. Guatemalan coffee is grown in the mountains and hillsides, making mechanization of the process impossible, said Leutert.

McQuillan noted, "The variety of coffee [in Guatemala] is different — it's grown in the shade and handpicked very carefully. Mechanizing the process would strip the plant and the bean."

Small farmers can no longer profit from growing coffee. "The coffee sector right now is not reliable," said Corbett. "The government of Guatemala is working to provide loans to the farmers, they are trying to address the issue, but the fact is the income from coffee hasn't changed. There is an international market problem."

The cost of production for a farmer is around $1.50 to $2 pound. But the product is sold at $1. "In 2017, a coffee farmer's net income was $2,000 a hectare, but in 2018, it dropped to $1,000," explained McQuillan. "It cut their income in half, and it's really difficult for a farmer to look after this family on this amount."

Del Valle Carrillo spent $98.70 to produce a 100-pound bag of parchment coffee. But he said, "The sale price is very similar, we are not making a profit. We are only holding the crop."

Co-operatives like Anacafé, the national association of coffee growers in Guatemala, is trying to address the issue, but the volatility of the market is a challenge difficult to overcome. Between 2013 and 2015, the organization managed price recovery after the initial spread of coffee rust. However, due to the international reference price, the income for producers decreased. Although Anacafé keeps no official data, field technicians reported farmers "abandoning some productive units because people have decided to go in search of new opportunities to cities or abroad."

Based on conversations with members of coffee co-operatives in the region, McQuillan reported 5% to 10% "members leaving for the U.S. every month."

"And these are farmers who are able to make a better deal for themselves, through direct trade relationships. If they are losing members at this rate, it's very troubling, because they are not able to be profitable anymore," he said.

Ground zero

Experts say that the prolonged drought and erratic weather in Guatemala is a direct result of climate change in the region.

"We are feeling the strongest impact of climate change," said Castellanos. "We are at the mercy of larger countries that produce climate change. They feel very less responsibility. They need to reduce greenhouse gas. And this is just the beginning, it could get worse."

Corbett said, "What we are seeing right now in the intersection of the unwillingness of the international community to address climate change and the inability of poor countries to do anything about it."

A farmworker walks through a coffee plantation in October 2017 in San Miguel Duenas, near Antigua, Guatemala. (Dreamstime/Lucy Brown)

The condition in Guatemala has also worsened since the Trump administration suspended aid to the country for not doing enough to curb migration to the U.S. This move has affected rural communities the most, and with no work and no food, people are now forced to make the journey north.

"This aid went towards helping a lot of people in rural areas," said Castellanos. "When you cut down or shut down the aid, it tends to have an opposite effect. With climate change causing food insecurity, cutting down on aid put additional pressure on the poor."

Despite the Trump administration's "zero tolerance policy" to prosecute all who enter the U.S. illegally and recent actions to limit asylum, the numbers continue to rise.

"What it tells me is that despite the obstacles, the condition is Guatemala is so bad that people think it's worth taking the risk," said Corbett.

Since his deportation, del Valle Carrillo is back to working in his coffee plantation. That's his only source of employment. He has learned how to control coffee rust, but finds it difficult to continue due to the high costs involved.

"One of my daughters, currently in the U.S., who is single, is the one who helps us from there with a little money," he said.

[Sarah Salvadore is an NCR Bertelsen intern. Her email address is ssalvadore@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter at @sarahsalvadore.]