"Drill, Baby, Spill," Michael D'Antuono, oil on canvas (Courtesy of the Ceres Gallery)

"Apis, the Honey Bee," Angela Manno, 2019, egg tempera and gold leaf on wood (Courtesy of the artist)

On the endangered Earth we inhabit, the resources for our survival include scientific research, political commitment, education of the public — and the artistic imagining of our plight. Data alone can never supplant the living imagination of Earth's inhabitants. All the more welcome then is a tightly focused, modest but exemplary exhibition at the Ceres Gallery in Manhattan that opened on Dec. 10 and runs through Dec. 14.

Curated by Marcia Annenberg and Ann Shapiro, the work of the 10 artists shown includes quietly beautiful images of imperiled nature, dramatic scenes of environmental degradation, and engrossing conceptual work that commands your reflection on the extinction of species and the depletion of the world's water supply.

The largest piece by far is Shapiro's "Raging Climate," a 65-by-95-inch digital print in 25 panels that shows a landscape devastated beneath a lurid sky of red, yellow, viridian and black (like El Greco on heroin). If it seems far-fetched, check out, elsewhere in the show, Joanna First's "Unsuspecting," whose gorgeous colors nevertheless suggest how easily we are fooled by appearances.

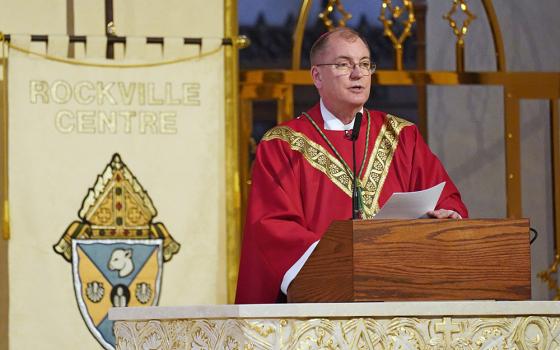

Michael D'Antuono's "Fossil Fool" presents just such a mistaken mortal, a skeletal figure in a parched desert desperately clutching American currency as oil rigs drill away in the background. (It's Ivan Albright in an ecological key.) His larger "Drill, Baby, Spill" would be an advertisement for a Caribbean beach vacation if the oil rigs on the horizon didn't tell you what the accouterments of the indolent young woman in her beach chair in the foreground already hadn't.

To remind us of our fundamental responsibility for choosing between such abuse of the natural world or peacefully allowing it to rest, Noreen Dean Dresser returns in her print series "The Root Amidst Good and Evil" to the Garden Scene in Genesis 3 and the serpent's temptation of Adam and Eve.

"Carbon is the marker for the age of life," she notes, "and carbon in our atmosphere may well reveal our collective folly. How will we manage the garden without acknowledging the garden's right to rest?"

Conceptual art is represented with subversive vigor by Joan Arbeiter. Known for her "Portrait of the Artist as a Young Girl" series as well as for a series of portraits of other women artists, Arbeiter has also done stirring work on environmental issues, chiefly in her "The Vanishing Vista" paintings from the late 1980s. Over warm and lovely landscapes, much in the style of Grant Wood, she prints reflections on our failed responsibility for the Earth — legibly, but requiring care to make out the text. (The medium is the message.)

"Hush My Kush," Marcia Annenberg, 2019, mixed media (Courtesy of the Ceres Gallery)

Annenberg has paid special attention to the suppression of climate news, coining the term "inverse propaganda" for news that isn't reported. At Ceres, she has a smack-in-your-face piece, "Hush My Kush," that compares the reporting of the Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment by The New York Times with its complete absence in seven other leading national papers — even though the water supply of more than a billion people in Asia is affected. It hangs from a curtain rod with a sheer white curtain and a red, white and blue rosette over the upper corner. Sweet domesticity over urgent news.

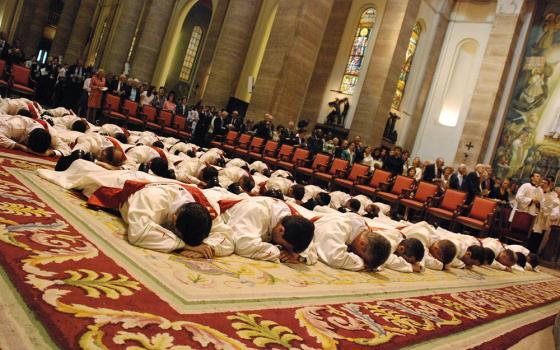

And then, hung quietly opposite each other, are two of my favorite artists in the show, Nigella Hillgarth, with seven examples from her "Disappearing Bird Series," and Angela Manno, with 10 sweetly mysterious icons.

Hillgarth, formerly the director of the New England Aquarium, offers an Audubon-like catalog of birds, though in photographs, with far more brilliant colors and a more engaged purpose. Scientists, she reports, estimate that in the last half century the continental United States has lost 29% of its total avian population, a loss of nearly 3 billion birds. The decline is due to construction, habitat loss and pollution — and, increasingly, climate change. Brooke Bateman, senior climate scientist for the National Audubon Society says pointedly: "Birds are important indicator species, because if an ecosystem is broken for birds, it is or soon will be for people too." The birds Hillgarth shows us are ravishingly beautiful. And threatened with extinction.

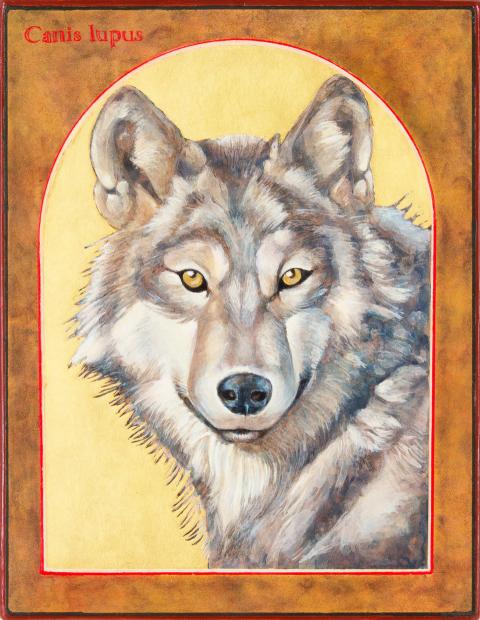

"Canis Lupus, the Grey Wolf," Angela Manno, 2019, egg tempera and gold leaf on wood (Courtesy of the artist)

In gold leaf, egg tempera and ground stone pigments, Manno's icons present not Madonnas or saints — her practice for 20 years before this show, after having trained with master Russian iconographer Vladislav Andreyev. Now they are remarkably lifelike animals, amphibians and insects. Importantly, their traditional religious form keeps her sympathy for her subjects from being sentimental. The 10 in the show, each 7 by 9 inches, include a gray wolf (whose gaze is hard to turn from), an Andean Flamingo (in magnificent pink), and a honey bee (whose hexagonally stenciled golden background is a work of art in itself).

A careful reader of biologist E.O. Wilson, Manno quotes his estimate that if current trends continue, half of earth's animal and plant species will be extinct by the end of this century. "The rate of extinction of species is nothing less than a holocaust of nature," she says. And so she is indeed consciously seeking "to transition from an anthropocentric worldview to a biocentric norm of reference." Her favorite quote comes from St. Thomas Aquinas:

Because the divine could not image itself forth in any one being, it created the great diversity of things so that what was lacking in one would be supplied by the others and the whole universe together would participate in and manifest the divine more than any single being.

See the show if you can. And learn from it that being informed about climate change, in order to be engaged about it, is surpassingly enriched when you learn to imagine it.

[Jesuit Fr. Leo O'Donovan is president emeritus of Georgetown University in Washington and a frequent commentator on the arts for NCR.]

Advertisement