A farmer harvests an improved variety of cassava in Les Anglais, Haiti, in 2010. Pope Francis and other Catholic leaders have called for international policymakers to pay particular attention to small farmers and farm families. (CNS/Barbara J. Fraser)

When Sr. Anne Falola was a girl in Ibadan, Nigeria, the city was home to half a million people. Many were farm families who worked in fields on the outskirts of the city when rains were falling, then devoted themselves to household tasks and cultural activities during the dry season.

Since then, metropolitan Ibadan's population has swelled to some 6 million, and urban sprawl has swallowed up many of the family farms. Needs have also changed, and over the years Falola, 55, who is now on the governing board of the Missionary Sisters of Our Lady of the Apostles, has watched as farmers have turned to cash crops suitable for export, using chemical fertilizers and pesticides to increase yields.

Those changes make farmers less able to withstand weather-related disasters like drought or flooding, which have displaced millions of people in Africa in recent years. And scientists predict that a warming climate is likely to increase the frequency of severe storms — like the back-to-back hurricanes that ruined crops in Central America in late 2020, forcing people to migrate from rural to urban areas and then northward toward the United States.

In a vicious circle, farmers suffer from a warming climate, but the way humans produce and distribute food also contributes to climate change, with agriculture and forestry accounting for as much as 40% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

The "green revolution" of the 1960s led to the rise of chemical-intensive, industrial scale agriculture. (Unsplash)

The combination of climate change and the upheaval caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has put millions of people around the world at greater risk of going hungry. The United Nations World Food Program estimates that the number of people suffering from acute hunger doubled during the pandemic, from 130 million in 2019 to 265 million by the end of 2020.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) plans to hold a summit in late September focusing on creating "healthier, more sustainable and equitable food systems." The concept of food systems refers to everything involved in getting food from the field to the table — not just farming, but also food processing and distribution. A pre-summit conference July 26-28, held both in Rome and virtually, was organized around five themes: universal access to safe and nutritious food, sustainable consumption, "nature-positive" production, equitable livelihoods, and resilience.

Ahead of the meeting, Pope Francis issued a message urging the participants to pay particular attention to small farmers and farm families, as well as to traditional knowledge about environmentally sound food production.

Paulo da Silva Bezerra, 56, checks a tree on his small farm in the village of Alive, outside Santarem, Brazil. Da Silva complains that chemicals sprayed on industrial-scale soy fields encroaching on his land have damaged fruit trees and other crops on his farm. (CNS/Paul Jeffrey)

The Vatican's Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development participated in the pre-summit conference. In remarks at a session on July 27, Cardinal Peter Turkson, who heads the dicastery, stressed the importance of drawing on the knowledge of Indigenous and traditional peoples, a topic he also emphasized at a virtual conference in June. He called the industrial-scale use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers "ecocidal practices."

Grassroots protest food summit

But a number of Indigenous and civil society groups were sharply critical of the event, saying the organizers were favoring corporate interests and sidelining small farmer organizations, Indigenous communities and other traditional peoples.

More than 150 civil society groups wrote to U.N. Secretary General António Guterres in February, protesting the appointment of former Rwandan Agriculture Minister Agnes Kalibata as his special envoy to the FAO summit. Kalibata also headed the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, which has emphasized industrial-scale, market-driven agriculture over family farms and traditional farming techniques. Earlier this year, a faith-based environmental institute in Africa called on the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to stop funding "green revolution" technology and policies in Africa.

Because of the pandemic, planning sessions for the summit and parts of the pre-summit conference itself were held virtually. The combination of a lack of reliable Internet service, living in distant time zones and not speaking English (the dominant language in meetings) put small farmers in the Global South at a disadvantage, said Michael Fakhri, U.N. special rapporteur on the right to food and a law professor at the University of Oregon.

'Whenever there's famine, hunger, malnutrition, it's not because of lack of food — it's always because of political failure.'

—Michael Fakhir, U.N. special rapporteur on the right to food

Giving corporations a greater role in the process tipped the balance even further, he said.

"If you don't have a system with clear rules of who can participate and how they can participate, and you just open the door, what happens is those who have the most power can shape the process and benefit from the process the most," Fakhri told EarthBeat.

For Vincent Dauby, agroecology and food sovereignty officer at CIDSE, a Catholic consortium of mainly European humanitarian and development agencies, giving corporations a large role undermined what should have been a participatory, democratic process.

In a world where millions go hungry despite the expansion of high-tech food production, "it's that [corporate] approach to agriculture that has gotten us to where we are right now," Dauby said.

CIDSE was among the groups that protested the pre-summit conference and sponsored a parallel event, the "People's Counter-Mobilization to Transform Corporate Food Systems," which featured a virtual rally and a series of roundtables and dialogues.

Corporate monopoly on food

Before the global "green revolution" of the 1960s, most food was produced on family farms. But the past half-century has seen a huge shift toward industrial-scale food production and distribution — and anyone who eats food should be aware of that, said Norman Wirzba, a theology professor at Duke University who has written extensively on food ethics, including Food and Faith: A Theology of Eating.

Over the past half-century, global food production, processing and distribution have become concentrated in the hands of relatively few corporate conglomerates. (Pixabay/Soydul Uddin)

The number of items on shelves in grocery stores gives the impression that "there's a tremendous amount of diversity in our food system," he told EarthBeat. "But the reality is that all of that diversity of products in a grocery store is basically controlled by four to six companies."

Large corporations dominate global food markets, selling seeds and agricultural chemicals to farmers and also controlling the processing and marketing of food.

"These conglomerates have a monopoly on what gets made, what gets grown. They set the terms for how it's grown, how much farmers get paid. They run the distribution networks, they do all the marketing, and they have a powerful lobbying presence in the halls of government," Wirzba said. "I think people need to be aware of this, because when you've got a food system that is dominated by a few companies and also controlled by these companies, you have to appreciate that their main interest is not the nutrition of eaters, it's not the health of eaters — their main interest is profit margin."

That "has really squeezed farmers, who already are working with very small profit margins, if there's a profit margin at all," he added. "The commodification of our agricultural system [and] our food has meant that everything is being driven by the logic of profitability. And that is not good for the land. It's not good for farmers. It's definitely not good for animals. And it's not been good for eaters."

Advertisement

What's missing from the FAO conversations, both Fakhri and Dauby said, is a focus on the right to sufficient, nutritious food.

"We still see people suffering from hunger or malnutrition, while at the same time, in the Global North, we have so much food and we waste it," Dauby said. "The system is rigged — it has to change. The objective is not the market. The objective is that people can live without hunger."

Climate change drives food conflict

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, climate change was threatening food supplies not only because of weather extremes but because of conflict, said Emily Wei, director of policy for Catholic Relief Services, the U.S. bishops' humanitarian and development agency.

"Climate is definitely a driver and an exacerbating factor of food insecurity. And then it compounds with conflict, it compounds with extremist violence, it compounds with livelihood, and it drives some secondary effects, like migration [and] displacement," Wei said.

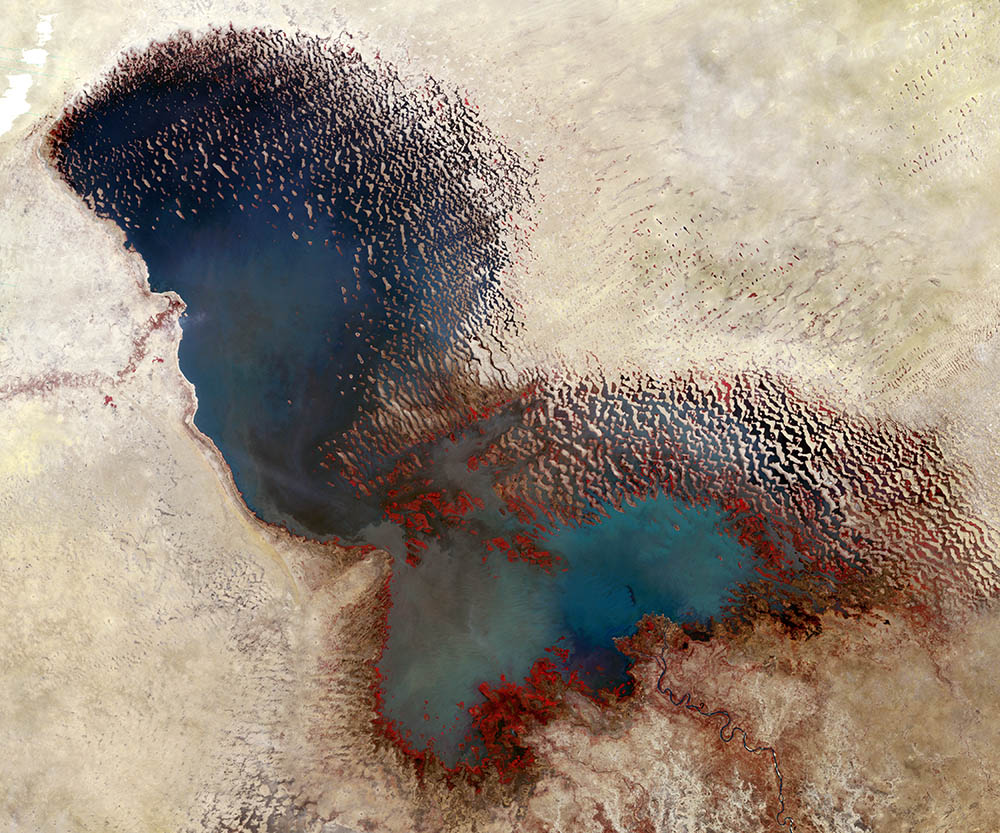

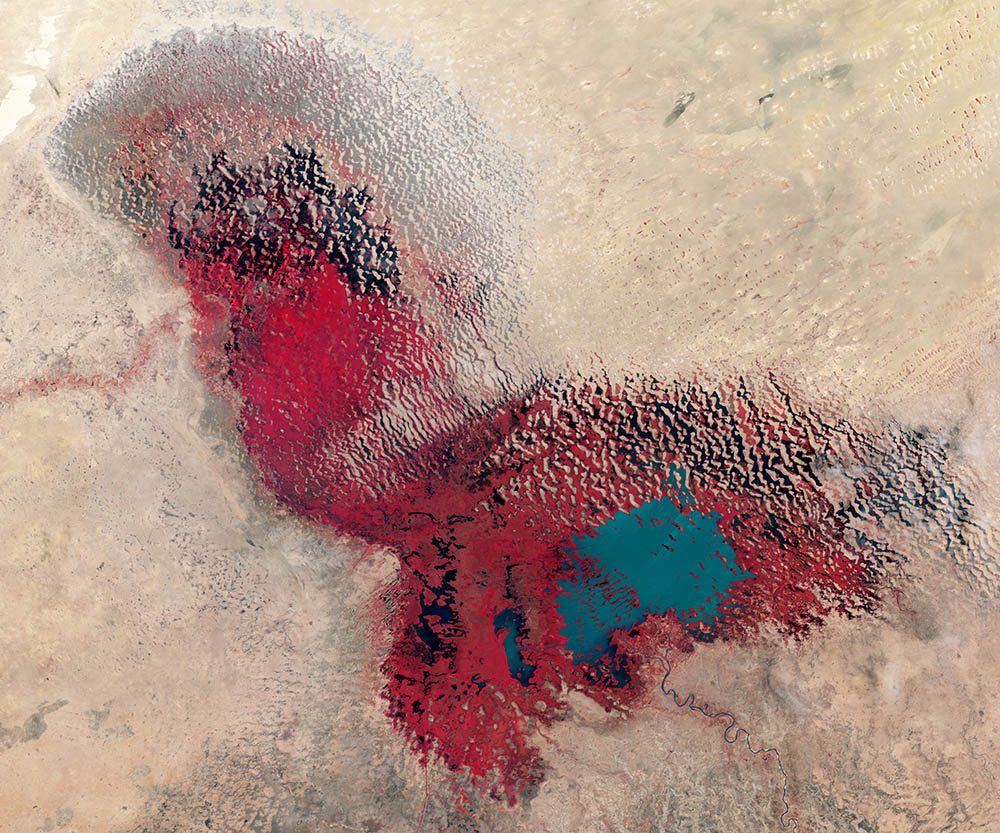

Falola has seen that play out in her homeland, where the once-enormous Lake Chad — a crucial source of water for farming and fishing for people in Chad, Cameroon and Nigeria — has shrunk by 90% since the 1960s.

"What that has produced is conflict," Falola said, as Boko Haram insurgents found new recruits among farmers and fishers who lost their livelihoods because of drought.

The lake's disappearance also meant the loss of dried fish that had been a key source of protein for people throughout the region. And it has pushed nomadic herders farther south in search of land for grazing.

But there they come into conflict with farmers in an area where farms are expanding, Falola said. Traditionally, farmers and herders shared the same area. Herders would tend their animals in fallow fields, where the manure provided natural fertilizer. The following year, farmers would sow crops in those areas and leave the previous year's land fallow for the nomads' herds.

As cities swallow farmland and farmers expand into new areas, the land available for grazing has shrunk, Falola said. The conflicts between herders and farmers have grown so violent that farmers are afraid to tend their fields when nomadic groups arrive, creating hardship for farm families and increasing the cost of food in surrounding areas.

"I see the root of that problem in climate change," Falola added. "And also I see the root of that problem in leadership, in governance."

Small farmers in northern Nigeria practice techniques aimed at helping them withstand the threats posed by a warming climate. (Courtesy of Missionary Sisters of Our Lady of the Apostles)

When power was in the hands of traditional leaders, they oversaw rules about land sharing, she said. Now, however, national governments often override traditional leadership, but politicians in distant capitals do not understand and cannot manage such conflicts.

A paradigm shift for food

The COVID-19 pandemic has further revealed the complexities of modern systems for growing, processing and distributing food — and the shortcomings of political leadership.

During the worst of the pandemic, in countries like the U.S., low-paid farm and food service workers were among those at greatest risk of exposure to COVID-19, in places like meat packinghouses or restaurants, and of losing their income, as many restaurants closed or cut back staff. In countries where most workers live from day to day, lockdowns that cut off their income quickly led to hunger.

Migrant workers wearing masks trim red cabbage at a Canadian farm in April 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Workers on farms, in packing plants and in the food service industry have been at high risk during the pandemic. (CNS/Reuters/Shannon VanRaes)

"Whenever there's famine, hunger, malnutrition, it's not because of lack of food — it's always because of political failure," Fakhri said. "To tell governments, 'You must transform your food system,' what you're telling them is you have failed, and you have to transform how you govern. It's not a matter of finding a clever idea or a technical fix or the right technology. It really requires political transformation."

The U.N. rapporteur sees the greatest hope at the grassroots, in events like the counter-mobilization against the food summit, where farmers, fishers, Indigenous people and others who all need access to the same resources and same spaces come together to seek solutions.

"They're using the right to food as a common language to overcome their differences and pressure their governments to change," he said. "People are exhausted, people are sick or dying, but they're also mobilizing, they're also coming together. So the task is how to keep that social and political organizing energy going."

Faith groups can play a role, said Catholic Relief Services' Wei, who advocates "local solutions for local problems." She encourages people to engage in grassroots advocacy with governments "to look at the systems and structures that can support local food systems."

Wirzba, the Duke theologian, sees the matter of food deeply entwined in all faith traditions.

"God in Scripture is continually involved in the feeding of people. If you read the Gospels, Jesus is feeding people all the time," he said. "Because when you prepare a meal for somebody else, you're declaring your love for them. So food is not a commodity. Food is a declaration of one's love for another."

Faith communities, he said, "need to be very clear in saying that food is not just a commodity, and that the eating of it is not just a way for these companies to maximize their profit share. We need to respect land. We need to respect agricultural workers. We need to respect eaters."

That, Wirzba added, "puts in motion an effort to try to promote a different kind of agriculture. It means that we try to advocate for food systems in which life is honored rather than degraded, in which land is honored rather than degraded."

Ultimately, said Dauby of CIDSE, "If we are waiting for policymakers to make the change, there will never be a change. We need a paradigm shift, but the paradigm shift has to be in every person."