A vehicle navigates a flooded road Sept. 14, 2018, during Hurricane Florence in North Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. The next year, the coastal city of Charleston experienced 89 days of flooding, nearly one every five days. Charleston's previous record, 58 times, was set in 2015. (CNS/Reuters/Randall Hill)

Flooding is a prevailing problem in Charleston, South Carolina.

In 2019, the Atlantic coastal city experienced 89 days of flooding, or nearly one of every five days that year. That blew past the previous record of 58 times, set in 2015, and represented a dramatic shift from more than a half-century earlier, when in 1950 flooding events occurred roughly twice a year, according to a recent study by the coastal ocean science center of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

In some ways, it's no surprise that Charleston regularly floods — it sits only a few feet above sea level, is next to an ocean and is surrounded rivers and tributaries. That makes it especially prone to storm surge from heavy rains and coastal storms, though flooding can also occur on sunny days, too. The hazards are exacerbated by climate change, which is causing more intense storms and is also causing sea levels to rise,

But that only partly explains the rise in flood events in Charleston, people involved in justice ministries said at a virtual workshop on Pope Francis' encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home." They point to development that has replaced critical marshlands with waterfront properties in one of the country's fastest-growing cities.

"If you build on that salt marsh, you're taking away that buffer from sea level rise, the buffer from floods, from storms as well as just a buffer in general," said Lee Ann Clements, a marine scientist and chair of the committee on integral ecology for the Diocese of St. Augustine, Florida.

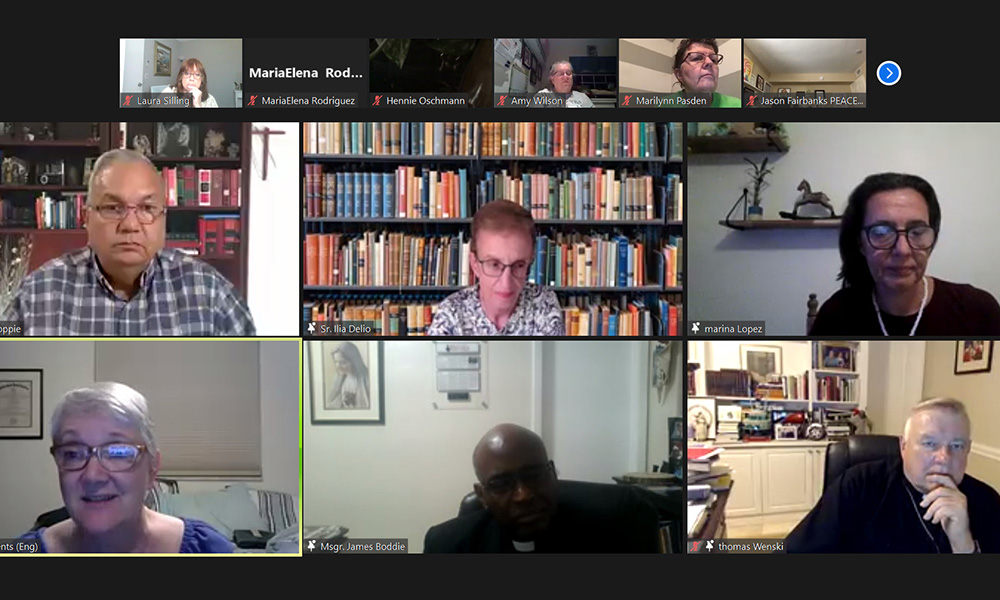

Lee Ann Clements, bottom left, marine scientist and chair of the committee on integral ecology for the Diocese of St. Augustine, Florida, speaks during the virtual Laudato Si' workshop Aug. 17. The workshop featured Franciscan Sr. Ilia Delio and Miami Archbishop Thomas Wenski, each of whom reflected on the pope's encyclical and how Catholics and others can respond to its message. (NCR screenshot)

"It's very easy for people to see that coastal environment, that waterfront property, as the thing they want, as desirable. But to the detriment of the whole environment and to the detriment of the community," she said.

The flooding has also intensified the southern city's racial and economic gaps. Black and poor communities are located in areas most prone to flooding, but they are least likely to receive assistance, said Marina Lopez, a member of Charleston Area Justice Ministry who has worked with Latino communities in the Lowcountry.

"We never have enough money for the poor neighborhoods and the things that need to be done in those places. But we are discussing without any concern the money that we are going to spend to save the more affluent neighborhoods," she said.

Advertisement

The situation in Charleston was one of several environmental challenges identified during the Laudato Si' workshop Aug. 17. The event was organized by the Direct Action and Research Training Center, or DART Center, and co-sponsored by five Catholic dioceses, Allegany Franciscan Ministries and the Catholic Campaign for Human Development (CCHD) of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. The workshop featured Franciscan Sr. Ilia Delio and Miami Archbishop Thomas Wenski, each of whom reflected on the pope's encyclical and how Catholics and others can respond to its message.

In July 2020, the Catholic Campaign for Human Development awarded a $500,000 grant to the DART Center, which is made up of 28 multifaith justice ministry organizations in the Southeast and Midwest, to put the principles of Laudato Si' into action in Southeast communities facing hazards from climate change. Seventeen DART-affiliated groups are building care for creation teams as part of the initiative, with the goal of identifying climate impacts in each community and mobilizing faith organizations to lobby for local policies to address them fairly and equitably.

The Laudato Si' workshop was the kickstart of a series of listening sessions planned for the coming months that seek to engage as many as 1,000 people in each of the 17 locations to continue discussing local impacts of climate change and solutions that benefit all people, particularly those who are poor and historically disadvantaged.

Josette Josue, a parishioner of St. James Catholic Church in North Miami, described how property values and rents are soaring in the Little Haiti neighborhood — located near the center of the city and therefore farther from the coast and rising sea levels — and forcing people to abandon a neighborhood where they've lived for decades.

"Haitian residents are moving out while wealthy communities are moving in," she said.

Wenski said that for Floridians concerned about rising seas, "the news was not good" in the recent report on the state of the global climate from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The archbishop said that a core message from Francis in Laudato Si' is that addressing the environmental challenges facing the planet begins with restoring broken relationships with God, with neighbor and with the Earth itself.

"We are all interconnected, and if we're going to solve the problems that beset us we have to recognize that," Wenski said.

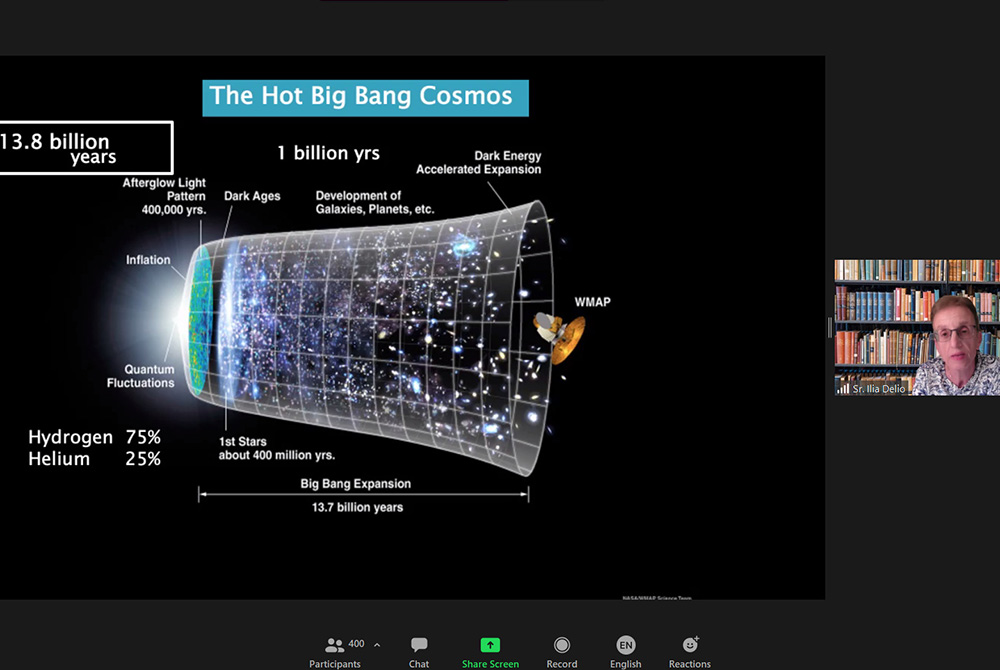

Delio, the Josephine C. Connelly Endowed Chair in Theology at Villanova University, said part of the problem is that humanity has become disconnected from the earth.

"We have built a very complex world for ourselves at a very rapid pace. And so we did not learn how to really live in this world adequately," she said.

Franciscan Sr. Ilia Delio speaks during the virtual Laudato Si' workshop Aug. 17. "We have built a very complex world for ourselves at a very rapid pace. And so we did not learn how to really live in this world adequately," she said. (NCR screenshot)

That has led to a selfish mentality, particularly evident during the coronavirus pandemic, of "take for me first, let me take care of myself first, and if I have anything left over, maybe I can help you," she added. "And that's a deep problem for us. We have no real sense that we really belong to one another and we belong to one another on this Earth."

Delio said that solving the problems of climate change and environmental degradation begins with changing ourselves, and that communities seeking to live in the spirit of Laudato Si' must reflect a sense of mutual caring and mutual sharing that sees the Earth as part of that community and not simply a repository of resources.

"The ultimate concern of the human must be the integrity of the universe upon which the human depends in such an absolute matter," she said. "Care for the Earth sounds like we're in charge, but the fact is the Earth cares for us. And if we destroy ourselves, it's likely that simple biological life will continue on."