A man carries his belongings through a flooded road in Marcovia, Honduras, Nov. 18, after the passing of Hurricane Iota. (CNS/Reuters/Jorge Cabrera)

Unrelenting rain from hurricanes Eta and Iota soaked and softened the mud bricks of the house where José Reyes lives with his wife, five of his eight children and a grandson in this remote village in southwestern Honduras.

"My house is made of adobe, and the wall cracked," the farmer told EarthBeat. "The house was damaged because of the water — so much water, so much water. I couldn't cover it."

He hopes to repair the house but doesn't know when that will be possible. Between the rain from two hurricanes in less than three weeks, and a series of rainy cold fronts expected to last until February, the ground is too waterlogged to make the bricks he needs to rebuild the wall destroyed by the storms.

Reyes' crops of corn, beans and coffee were also damaged by the two tropical storms, which swept through Honduras in rapid succession between Oct. 31 and Nov. 18. Floodwaters from a stream near Reyes' home swept away trees suitable for timber and part of his coffee field, which was on a hillside. His corn crop was ruined before he could harvest it.

"There's no way of fixing that. Aid hasn't arrived; it seems like it's just on paper," he said, adding that his village of El Trapiche needs assistance to make roads passable again.

According to civic and business groups, at least 100 people have died, damages top $10 billion and some 1 million Hondurans have lost their jobs or their source of income in the informal economy. Experts say the damage, which comes amid the economic and health crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic could set the country back more than 20 years.

The areas hardest hit by the storms are Valle de Sula, which is the economic motor of Honduras, and the department of Gracias a Dios, the country's most remote area, where crops and homes were destroyed, and people and livestock died. Honduras had not been so devastated by storms since Hurricane Mitch in 1998.

Government officials have not completed a damage assessment, but so far, large-, medium- and small-scale farmers in the country's northern and western regions have lost nearly 80,000 acres of plantains, bananas, coffee, beans, rice and corn. Flooding also threatens more than 400,000 acres of sugarcane and oil palm plantations.

People wade through floodwaters in La Lima, Honduras, Nov. 5 in the rain-heavy remains of Hurricane Eta. (CNS/Reuters/Jorge Cabrera)

Advertisement

Drought, storms disastrous for farmers

"Honduras has always been one of the countries most vulnerable and most exposed to the effects of climate change, because of its geographic location, geography and productive structure," Conor Walsh, Catholic Relief Services country representative in Honduras, told EarthBeat. "It doesn't take much more study to trace a direct line between what people are experiencing and the effects of climate change."

Before Eta and Iota, forecasters hoped that this year's rainy season would bring enough precipitation to produce a better harvest than in the past few years, but the abnormal rains have been disastrous for agriculture in Central America, resulting in a grim outlook for the entire region, he said.

In an area of high temperatures and low rainfall known as the dry corridor, which stretches across Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, a multi-year drought has reduced the income and the food supply of at least 3.5 million people, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization. Honduras' dry corridor includes 132 of the country's 298 municipalities, mainly in the southern, western and central regions of the country.

In this area, which has the least access to irrigation water for crops, farmers lost between 50% and 90% of the fields where they produced pineapple, corn, beans, coffee and other export crops. The problem with beans, a dietary staple, was mold caused by the extreme dampness, which destroyed the harvest for farmers like Reyes.

The most recent storm left many people without homes, an income, farmland capable of producing crops or a safe place to return to, Walsh said. Many people have already taken refuge in cities, and the hurricanes are likely to result in a huge flow of migrants seeking better living conditions in other countries, including the United States.

People walk through debris in a road in Toyos, Honduras, Nov. 4, following Hurricane Eta. (CNS/Reuters/Jorge Cabrera)

Because this is the first disaster of this type in the country since 1998, the Honduran government has requested temporary protection status for those who seek to migrate to the United States, in an effort to start from scratch and improve their lives and those of their families.

It is understandable that migrating is the most attractive option for those who were hardest hit by the storms, Walsh said, because so far the government has announced no plan for rebuilding what the rains swept away.

The storms worsened the already-precarious state of food security in the country, he added. "It sounds awful, but this has been the last nail in the coffin."

As of October, it was estimated that between 550,000 and 990,000 people in Honduras would not have access to food in 2021, according to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network. That figure is likely to increase, Walsh said, because three years of drought and two devastating tropical storms have battered Central America's economy, which depends heavily on the export of basic food crops, sugar and fruit.

Visible effects of climate change

Both the prolonged drought and this year's atypically severe hurricane season are among the effects of climate change, Walsh said.

The hot, dry weather early in the year fueled an increase in the number and extent of forest fires between March and May, making the fire season "one of the worst in the past decade. Undoubtedly, that contributed to the vulnerability of the soil, leaving it hardened and without plant cover that would allow rainwater to filter into it," he said.

"Climate change means that the rain, when it comes, is more intense and comes in the form of storms and flooding," he added. "This is what experts and scientists predicted, and now we are living it in the flesh."

Deforestation also worsened the disaster by contributing to landslides in various parts of the country.

To some extent, rain and flooding are beneficial to ecosystems in Honduras, as they carry fresh sediments and nutrients from the mountains to the agricultural valleys, biologist Walther Monge told EarthBeat. Heavy flooding, however, washes away soil and nutrients, leaving behind mud that will not support the bananas, corn, coffee and beans that are the country's staple crops.

Officials have reported 77 deaths from Hurricane Eta and 22 so far from Iota, although experts say the figures could increase, because it has been impossible to reach the most remote areas of the country. Floodwaters remain high, and there are daily police reports of bodies found in rivers and streams.

Storm damage to infrastructure affected at least 1 million people in 16 of the country's 18 departments, cutting off transportation for nearly a quarter of a million people in villages and cities in northern and western Honduras. As of Nov. 30, the Comisión Permanente de Contingencias, the government's disaster agency, had tallied 27 bridges destroyed and 25 others damaged, as well as 748 stretches of road affected and one airport closed because of flooding.

One building that suffered heavy damage in the central part of the country was the chapel of the General Cemetery in Tegucigalpa. The chapel, built in 1954, had deteriorated over time, but heavy rains from the two hurricanes soaked the building's walls and roof and caused a side wall to collapse. Workers were trying to keep the entire chapel from crumbling.

Paint peels from rain-soaked wall of chapel at General Cemetery in Tegucigalpa. (Fernanda Aguilar)

Disaster worsens health crisis

Government officials and other experts fear that the storms will worsen the health crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

Honduras' health system, which was already weak, has collapsed under the strain of COVID-19. There are not enough hospital beds, intensive care units or ventilators; protective equipment for health workers is scarce; and the country lacks the funds for adequate testing. Doctors and nurses in both public hospitals and private clinics have fallen ill with COVID-19, and some have died.

As of Dec. 6, the government Health Secretariat had recorded more than 111,000 cases of COVID-19 and 2,946 deaths.

Doctors and scientists in Honduras worry that the flooding and mud, as well as conditions in overcrowded shelters and unsanitary food and water conditions, could lead to a spike in COVID-19 cases, as well as mosquito-borne diseases, and more respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses.

These cases could be further complicated by preexisting conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes. Experts also worry about mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety. With health centers overwhelmed since March, there is little ability to handle more patients, they say.

Hugo Fiallos, an intensive care specialist at the Honduran Social Security Institute, said decision makers have ignored the advice of experts in risk management, health and economics.

"When we warned that something like this could happen, they didn't pay attention to us, and now we're paying the price," he said, referring to protests in 2018 to demand improvements in Honduras' health network.

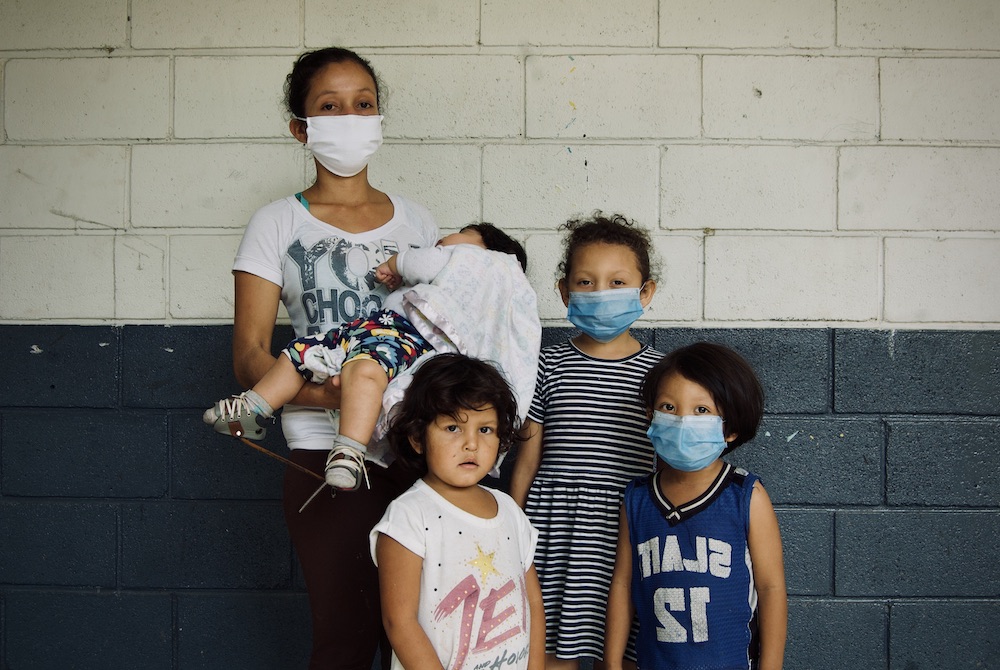

Jessy Nohemí Rosa Durón, 24, stands with her three children and another girl in a shelter in Comayagüela, Honduras, for people displaced by the hurricanes. Her youngest child needs orthopedic shoes that cost more than $300, but the single mother has been able to save only $100 so far. (Fernanda Aguilar)

An estimated 19,000 families — more than 95,700 people — have taken refuge in more than 1,000 shelters in the country. There have been few media reports about health conditions in the shelters, but people in several refuges in the central district of the country said they had not been tested for COVID-19 or received basic medication, such as analgesics.

After reports of efforts to evict families from shelters in the cities of San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa, the capital, Cardinal Óscar Andrés Rodríguez Maradiaga called for Hondurans, especially government employees, to attend to the needs of those displaced by the storms.

"Yesterday we heard how some people who are in shelters have been told to leave," he said in his homily on Nov. 15. "Why? They don't have a home or anywhere to go. Are they going to get a new house by magic?"

The cardinal urged his listeners to learn a lesson from the disaster.

"Let's not waste the gift of our life," he said, "and let's not live a superficial life, unaware, looking outside for pleasure, power and money."

The poor and those who suffer cannot wait, he said, urging the faithful not to become infected by "the virus of indifference."

[Lizz Mejía Raudales is a Honduran journalist based in Tegucigalpa. She currently works with the independent digital publication Contracorriente.]