Protestors marching in New York City on the fifth anniversary of Hurricane Sandy (Erik McGregor)

Editor's note: This story, originally published by the Nexus Media News, is republished here as part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration committed to strengthening coverage of the climate story.

President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden are in a dead heat in Texas, a state that has swung Republican in every presidential election since 1976. If Biden pulls off the unthinkable and defeats Trump in Texas, it will be by mobilizing Latino voters.

This fact could play into the ongoing debate in Democratic circles over the party's position on climate change, which is a leading issue for Latinos. Biden's climate advisory council, led by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and former secretary of state John Kerry, has put forward an ambitious climate plan that bans fracking and oil exports — policies that could turn out Latinos in states like Texas and Arizona. This stands in contrast to Biden's current, relatively modest climate plan, which permits fracking, a concession to gas-rich states like Pennsylvania and Ohio. Sources told Reuters that the more modest plan is likely to win out. This could come at the cost of Latino votes.

"Given what we know about Latinos and their interest in voting for candidates who are pro-climate, we think they are a really important group that could be mobilized," said Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. "They could potentially make a really big difference in states like Texas and Colorado and Arizona."

Latinos are really worried about climate change, but Democrats and climate advocacy groups aren't capitalizing on this fact.

Latinos consistently vote in smaller numbers than other groups. The reasons are varied. Latinos often face structural barriers, like onerous voter ID laws or long lines at polling places. Many are immigrants or the children of immigrants and have never voted nor seen their parents vote. The biggest factor, however, may be that politicians are failing to reach Latinos or failing to speak to issues Latinos care about, said Victoria DeFrancesco Soto, assistant dean for civic engagement at the University of Texas.

"There is a need to attack apathy," she said. "While structural barriers do have an impact, the problem is apathy and figuring out what policies connect most to people." Consistently, Latinos say they want policies that address climate change.

"Many people assume that the only people who really care about climate change are white, well-educated, upper-middle-income, latte-sipping liberals, and it's just not true," Leiserowitz said. "Actually, the racial and ethnic group that cares more about climate change than any other is Latinos."

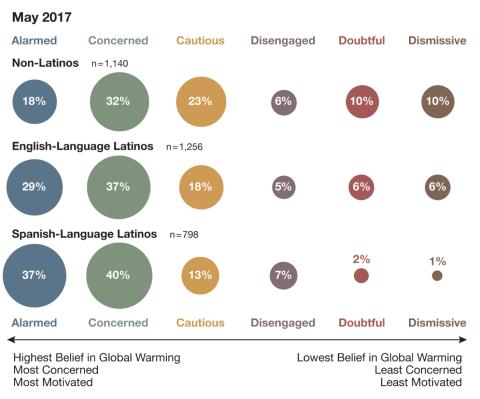

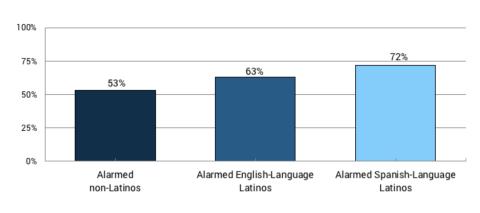

Compared to other groups, Latinos are more worried about the crisis, more willing to take action, and more likely to say they will vote for a candidate because of her stance on climate change. Leiserowitz and his colleagues have sorted Americans into six groups according to their views on climate change, ranging from the "Alarmed," who are most exercised about the problem, to the "Dismissive," who think it's a hoax. Latinos — Spanish speakers in particular — are far more likely to count among the "Alarmed."

Leiserowitz said that, broadly speaking, Latinos are worried about climate change because they are more likely to hold an egalitarian worldview. Latinos fear climate change will worsen inequality, a concern that is often born out of personal experience. After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico, for instance, the federal government left the island to languish, allowing many survivors to slip into poverty.

While climate change remains a top-tier issue for Latinos, the political class has yet to act accordingly. "Alarmed" Latinos are less likely than other "Alarmed" Americans to say they have been contacted by an organization working on climate change, a shocking failure of public outreach.

"That is the whole point of an advocacy organization — they recruit people," said Leiserowitz. "I think there are plenty of reasons to be engaging this community and really investing in this community."

Democrats can't rely on anti-Trump sentiment to mobilize Latinos.

In one sense, Trump is already doing everything he can to spur Latinos to the polls, not just through his mistreatment of Latin American immigrants, but also by failing to address climate change. Hurricane Maria, a storm made more severe by rising temperatures, spurred many Puerto Ricans to move to the mainland, where they are able to vote in the upcoming presidential election.

But Democrats can't count on Trump to mobilize Latinos, DeFrancesco Soto said. And their outreach to Latinos must speak to more than just concerns about immigration.

"I think that there needs to be more attention paid to economic needs and structural inequities that Latinos face. Immigration needs to be a pillar of the platform of reaching out to Latinos, but not the main one," she said. "They have to feel that the system takes into account their voice."

Democrats can make their case by pushing for ambitious climate policy that also tackles economic issues, said Ramón Cruz, the current president of the Sierra Club, the first Latino to hold the position. The Green New Deal aims to curb pollution from highways, factories and power plants in communities of color and to create jobs in those same communities.

"Construction, manufacturing, agriculture — all of those could benefit greatly from the Green New Deal," Cruz said. "It is boosting the sectors of the economy that are very important for the Latino population." He added that economic stimulus will be especially critical for wooing Latinos, who have been hit especially hard by the recession.

Cruz said the Sierra Club is working to mobilize Latinos, and that his election as the club's president is, in part, a recognition of the central role that Latinos play in the climate movement. He said the Sierra Club is publishing materials in Spanish and reaching out to groups in key states like Arizona and Florida.

"Clearly, there are a lot of people who would like to see him gone, but the challenge is how to mobilize those people," Cruz said. "We need to activate our base, and we need to ensure that the message is consistent with a clean economy."

[Nexus Media News is an editorially independent climate change news service affiliated with Climate Nexus, a nonprofit working to improve public understanding of climate change.]

Advertisement