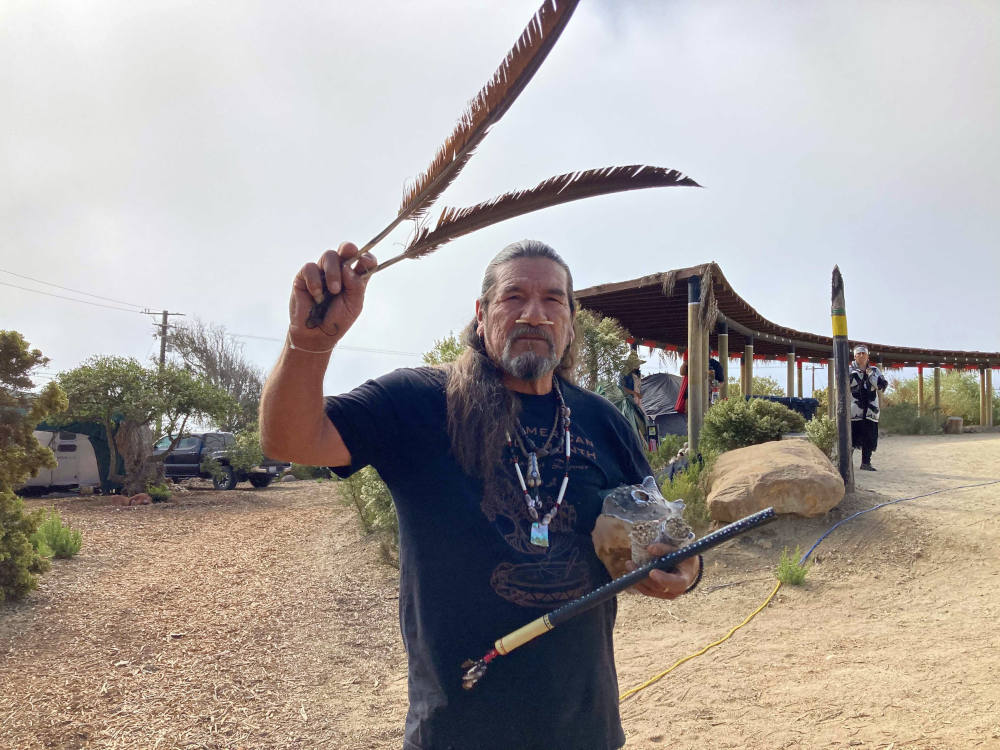

Apache Stronghold, a coalition of Apaches, other Native peoples and non-Native supporters seeking to preserve Oak Flat, arrives at Wishtoyo Chumash Village to begin a ceremonial circle, Sunday, Oct. 17, 2021, in Malibu, California. (RNS photo/Alejandra Molina)

To Apache Stronghold founder Wendsler Nosie, Sr., it's going to take just about a miracle to win their case to preserve the Apache sacred site in Arizona known as Oak Flat, given how "deceitful" he said it was for Congress to authorize the transfer of the land to Resolution Copper, a company owned by the British-Australian mining giant Rio Tinto.

"When I say that we're going to need a miracle, it means that the judges are going to sit there and have to make a moral decision — what they really mean when it comes to the Constitution, when they say freedom of religion, freedom of speech," Nosie told Religion News Service on Sunday (Oct. 17).

Nosie along with his family and members of Apache Stronghold — a coalition of Apaches, other Native peoples and non-Native supporters seeking to preserve Oak Flat — gathered Sunday at the Wishtoyo Chumash Village in Malibu in Los Angeles County. Leaders, elders and representatives from the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation, the Gabrielino Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians, the Costanoan Rumsen Carmel Tribe and others offered prayers and blessings for protection of Oak Flat and for the Apache Stronghold.

The gathering was one stop on a spiritual convoy to San Francisco, where a court on Oct. 22 will hear an appeal the group has filed to keep the land from being transferred.

The group began its trek in Arizona, meeting with Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, Arizona, and members of the Native American club at Brophy College Preparatory, a Jesuit high school in Phoenix that participated in a protest run earlier this year in support of Oak Flat. The group also met with the Salt River Pima–Maricopa Indian Community near Phoenix.

Next, they'll gather for a vigil at the U.S. Federal Building and at the Civic Center Plaza in San Francisco, offering prayers and songs for a positive outcome in the case that Nosie, his family and supporters often refer to as a "spiritual" and "holy war."

"Growing up we were taught that spirituality is first. Everything we've ever done as a people is prayer first ... We were told it wasn't going to be easy because the oldest fight is our religion," said Nosie's daughter, Vanessa.

"The only way we're going to win is through spirituality," she said.

Leaders stressed unity among the different tribes and communities represented on Sunday, with Mati Waiya, founder and executive director of the Wishtoyo Chumash Foundation, leading a ceremony, saying, "We have to stop this nonsense of separating ourselves.

"It's an honor to receive our brothers and sisters and to be able to help them on their journey to the ninth circuit so that we can be heard," Waiya said.

Oak Flat, known in Apache as Chi'chil Biłdagoteel, is a 6.7-square-mile stretch of land east of Phoenix that falls within Tonto National Forest.

The Apache people hold a number of important ceremonies at Oak Flat that, according to their court filings, can take place only on the site, which would be destroyed by mining. The Apache believe Oak Flat is a "blessed place" where Ga'an — guardians or messengers between the people and Usen, the creator — dwell.

Congress approved the transfer of the land to Resolution Copper in 2014 as part of the National Defense Authorization Act in exchange for 6,000 acres elsewhere.

In a statement, a Resolution Copper spokesperson said it "continues to consult and partner with local communities and Native American Tribes to guide further shaping of the Resolution Copper project and the significant benefits it will deliver."

"Resolution Copper is an important part of the region's economic future and the entire country's clean energy transition," the spokesperson said.

Apache Stronghold, which is receiving legal help from the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, filed a federal lawsuit to stop the land swap, arguing that destruction of Oak Flat would violate the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

Nosie, former chairman of the San Carlos Apache Tribe, has spoken about the importance of different Native groups banding and praying together to combat evil, which in this case, he said, is the capitalism embodied by Resolution Copper.

On a bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean, participants on Sunday gathered in a ceremonial circle, leaving offerings and sharing with Nosie and his family why they felt connected to Oak Flat.

A woman offered an Islamic prayer, and Carla Munoz, tribal councilwoman of the Costanoan Rumsen Carmel Tribe, sang a song in the Rumsen Ohlone language about the nourishment and gathering of acorns. Luis J. Rodríguez, author of "Always Running," shared about his mother's Tarahumura ties and about reconnecting with Indigenous practices.

Shannon Rivers, a member of the Akimel O'otham, offered an apology to the Nosie family during the ceremony for the colonization that he said "has pitted tribes against one another."

"Generations ago, we were asked to fight against the Apaches and control that area," he said. "As an O'otham person who follows tradition, it is important that we stand near them for the fight against ongoing colonization, ongoing violence against Mother Earth," he said.

Advertisement

Mariza S. Sullivan, tribal chair for the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation, said she was there Sunday because "I have a shared history."

"We consider the land sacred. We can also have that same commonality with other religions and how they choose to worship and how that might be taken away from them. It can happen to anybody," Sullivan said.

"To be able to worship what and where and to not actually witness the destruction of it, is common for all of us," she added.

To Josh Andujo, tribal member of Gabrielino Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians, "what's going on in Oak Flat is going to be an awakening for other Natives to challenge the government over religious freedom."

"I think for religious people, they're used to going to buildings to worship their religion. I don't think they understand our ways of life, but it's good to show that we didn't have buildings to worship. We were out here. This is our church," said Andujo, who is also Apache from his father's side.