Two Bishop O'Dowd High School students enjoy the Oakland, California, campus' Living Lab. (Courtesy of Bishop O'Dowd High School)

Note: The majority of this reporting was finished before schools across the country closed in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

In February, Michael Downs met with a group of student leaders at a Catholic high school to discuss their experience with environmental education. The students told Downs that when they go to college, they plan on using fewer plastic water bottles.

He wasn't thrilled about what he heard at the school (not the school where he has worked for the past four years). "Heavy hearted," he said, better described his reaction. After four years, that was their big takeaway?

It's not that reducing plastic waste is a bad goal. "That's great," Downs thought, but it's certainly not enough.

"How do we cultivate students who are like, 'I want to stop driving,' 'I want to pound on doors of politicians,' 'I want to change our relationship to stuff?' " Downs told NCR's EarthBeat.

In other words: How can schools provide students with an education the climate crisis truly requires?

Pope Francis detailed the stakes of this "great cultural, spiritual and educational challenge" in his encyclical "Laudato Si': on Care for Our Common Home." He wrote that it "will demand that we set out on a long path of renewal."

As the director of justice and kinship at Bishop O'Dowd High School in Oakland, California, it's Downs' job to think about how to meet this challenge.

"What the climate crisis is demanding," he said, "is a kind of radical action" or "radical mindset shifting." Fortunately, Downs and other Catholic school educators belong to a tradition that he said prioritizes mission.

Michael Downs, director of justice and kinship at Bishop O'Dowd High School, Oakland, California (Courtesy of Bishop O'Dowd High School)

Downs' workplace is one steeped in a long history of environmental education and action. "Kinship with creation" is built into O'Dowd's mission statement. Rumor on campus has it that it was the very first high school in the country to offer an environmental studies class back in 1968.

That legacy has evolved into a vibrant, multi-faceted culture of sustainability thriving at O'Dowd today. That culture begins freshman year, when all students are required to take an Earth science course as well as complete 10 hours of community service on a sustainability-related project. The campus itself includes a "Living Lab" — a 4-acre outdoor classroom and sustainable garden — that is maintained by a group of seniors called "EcoLeaders."

Last school-year, O'Dowd offered a new spiritual ecology elective course using Laudato Si' as a textbook. Downs developed the class with an Advanced Placement environmental science teacher. This year, enrollment doubled.

Did we mention the school has a sustainability coordinator on staff? Well, there you go.

Downs credits O'Dowd's culture to the school's successful leverage of Laudato Si'. The document has allowed the administration and staff to make care for creation "a real mandate," he said.

In his time at O'Dowd, Downs has met a number of alumni who, inspired by their high school education, have gone on to successful careers in sustainability. Environmental lawyers, sustainable business developers and biology graduate students regularly visit their alma mater. They represent the results of an O'Dowd education and serve as role models to current students for what is possible.

But those are single individuals, and Downs acknowledged that ecology and sustainability don't resonate equally with all students. Moreover, O'Dowd is only a single institution, and addressing the climate crisis will require widespread conversion.

"How do we have what the pope says about changes of heart and not just changes of habit?" Downs wonders.

The creation care team at Bishop O'Dowd High School, Oakland, Califorina (Courtesy of Bishop O'Dowd High School)

For the past half-decade, Salpointe Catholic High School in Tucson, Arizona, has dedicated itself fully to answering this question. Following the release of Laudato Si' in 2015, Salpointe (a Carmelite school) began collaborating with the Carmelite NGO — the advocacy organization attached to the Carmelite religious order. Together, the two organizations developed an entire curriculum based on the encyclical's content.

In 2016, Salpointe became the first school in the country to implement Carmelite NGO's "Curriculum on Laudato Si' " — a set of lesson plans that incorporate concepts from the encyclical in classes across all disciplines. The curriculum builds on existing learning standards, connecting the encyclical to material that is already being taught.

There are lessons on topics like energy and resource management, the works of mercy and environmental protection laws.

"We want our kids to appreciate that they can be change makers," said Kate McGarey-Vasey, a theology and humanities teacher at Salpointe who was on the original committee that developed the curriculum.

"We need to make our kids understand that it is absolutely in their power to make a strategic difference now and in the future," she said.

The message seems to be landing. McGarey-Vasey recently surveyed a group of 60 juniors on their opinions about climate change. She found that 55 of the 60 indicated they were aware and concerned about climate change, and they were taking that into account for future planning. These numbers are in line with a broader trend in the longtime Republican state. A 2019 poll by OH Predictive Insights, a Phoenix-based research firm, found that a majority of Arizona voters, regardless of political party, acknowledge and are "extremely concerned" about climate change.

In its first five years, McGarey-Vasey said the curriculum's greatest strength has been the freedom it provides teachers. Rather than mandating which specific components from Laudato Si' are emphasized, teachers are given the flexibility to pull out the messages of love that most resonate with them.

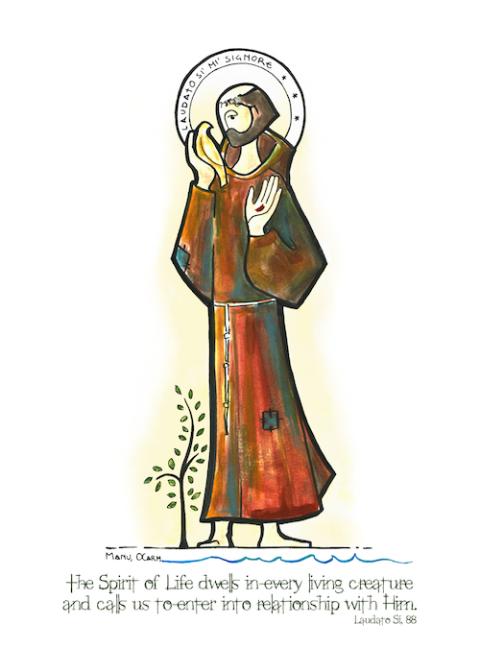

This image, designed by Salpointe Catholic High School's chaplain, a Carmelite priest, hangs in the school president's office, Tucson, Arizona. (Courtesy of Salpointe Catholic High School)

"There's just been a richness and an invitation to creativity," McGarey-Vasey said.

Salpointe has been extending that invitation far beyond its own campus as well, presenting the curriculum in Rome in 2017 to all Carmelite schools worldwide, in Chicago in 2018 to American Carmelite schools, and at Creighton University in 2019 at a Catholic climate conference. Most recently, during the first week of February, 12 teachers from across the country visited campus to actually see the curriculum in action as part of a "Laudato Si' Showcase."

Still, Salpointe's administration told EarthBeat they did not know how many schools, if any, have adopted the Laudato Si' curriculum.

"Looking at challenges for tomorrow, will there be a core organization to bring Catholic schools together to talk about this? Who will that be? Who will fund it? Who will bring it to life?" said Kay Sullivan, Salpointe's president.

Along those lines, the National Catholic Educational Association has developed an interdisciplinary method for teaching science called STREAM (which stands for Science, Technology, Religion, Engineering, Arts and Math). Since 2013, the association has hosted multiple nationwide conferences for teachers promoting STREAM — now using Laudato Si' as a foundational text.

"If there's going to be a resolution [to the climate crisis], it's going to come from [students'] knowledge, care and stewardship," said Heather Gossart, director of coaching and mentoring at the association. "But it has to be an educated stewardship."

Like Salpointe, the association also lacks data on the number of schools implementing STREAM.

Timothy Uhl, superintendent of Montana Catholic Schools and host of the podcast "Catholic School Matters," told EarthBeat that climate change is not taught very much at schools in his state.

But that's not because people in Montana are climate change-deniers, Uhl said. He personally has never once "met a farmer or rancher who doesn't say the climate is different." Instead, Uhl thinks politicization and polarization can make people in predominantly red states like his "a little leery" of embracing climate education. When you start talking about climate change, people worry they might "be accused of being a liberal."

Advertisement

There's also a systematic question involved. What is taught in a Catholic schools' classroom, Uhl said, depends largely on various education standards and priorities laid out by bishops.

"In my position, I want to make sure I'm moving with the support of the bishops. Principals would want to know they're moving with support of the superintendent. Teachers want to make sure they're moving with the support of the principals," he said, also noting that to his knowledge Laudato Si' has not made it into any Catholic high school textbooks.

Currently, despite the pope's assertive language on the topic, climate change has not risen to the top of the concerns listed by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. At their November 2019 meeting in Baltimore, conference president Cardinal Daniel DiNardo told reporters climate change is an important issue, but not yet "urgent." The bishops listed abortion, on the other hand, as their "preeminent" priority. (And because of the coronavirus, their June assembly in Detroit was canceled.)

A similar attitude is reflected in certain diocesan curriculum standards, even in historically more liberal areas. In the Chicago Archdiocese, for example, the phrase "climate change" does not appear anywhere in its high school science standards. Even though the reality of climate change is now recognized by scientific consensus, Chicago's high school standards include language like "possible global warming."

Downs, the high school administrator from Oakland, said he believes that if more bishops and state bishops' conferences explicitly outlined regional responses to Laudato Si' it would give "Catholic institutions the power and permission to sink our teeth into it." He said the California bishops' 2019 pastoral statement, "God Calls Us All to Care for Our Common Home," helped justify and elevate the sustainable culture at Bishop O'Dowd High School.

There is a section in the California pastoral statement dedicated to youth and young adults that outlines five action statements. The fifth calls on students to "actively participate in the political process to advocate for environmental justice."

On September 20, 2019, 400 students from Bishop O'Dowd did just that, joining about four million other activists around the world in a global climate strike.

In the lead up to the protest, Downs reflected on his students' leadership and his role as an educator in a Small Earth Story for EarthBeat. He wrote:

"Walking to targets in government, finance, and energy, they will let key stakeholders know where they stand. And where will my colleagues and I be? Standing behind them, with them."

[Jesse Remedios is a staff writer with National Catholic Reporter's EarthBeat and former NCR Bertelsen intern. His email address is jremedios@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter: @JCRemedios]