Hazel Johnson (1935-2011) is considered by many to be the mother of environmental justice. For more than 30 years, she pressed local officials and corporations to clean up toxic waste and pollution in her southeast Chicago community of Altgeld Gardens. (Courtesy of People for Community Recovery)

She was a community activist.

She was an ambassador of Altgeld Gardens.

She was an early mentor to Barack Obama.

She was a "thorn in the side" of the Chicago waste industry.

She was a wife and mother of seven children.

She is the mother of the environmental justice movement.

For more than 30 years, Hazel Johnson worked to clean up her corner of Chicago's southeast side. Her relentless advocacy made her a fixture in local news, and her story has been told in profiles and books and kept alive among her peers in the struggle for environmental justice. But one aspect of her life that's been less explored is her faith.

Hazel Johnson was also Catholic.

"It was her faith that got her to the place where she is today," said her daughter Cheryl Johnson.

Ten years after her death in January 2011, at age 75 from congestive heart failure, Johnson's contributions to environmental justice continue to resonate — at a time when the movement has reached new heights around the country and in the White House.

Hazel Johnson outside the office of People for Community Recovery, which she started in 1979 so residents of Altgeld Gardens could advocate for repairs in their community. (Courtesy of People for Community Recovery)

Altgeld Gardens: the 'toxic doughnut'

Tracing the birth of the environmental justice movement traditionally leads you to Warren County, North Carolina, where in 1982 civil rights activists and environmentalists staged a sit-in to protest toxic waste dumping in a predominantly African-American community.

Three years earlier, Johnson began People for Community Recovery, a grassroots nonprofit to push for cleaner, healthier conditions in Chicago's Altgeld Gardens housing project just off the southern tip of Lake Michigan and near the Indiana border. Around the same time, Robert Bullard, known as the father of environmental justice, was studying landfills in Houston, which his team of researchers discovered were located primarily in Black neighborhoods.

"It's like we were on parallel tracks," he told EarthBeat recently.

To know Johnson first means knowing Altgeld Gardens.

The neighborhood where she lived for five decades opened in 1945 as a public housing project for African American veterans returning from World War II and factory workers, and as a response to housing shortages as thousands of Black families moved from the South to the North during the Second Great Migration. The 190-acre neighborhood now has roughly 1,500 housing units.

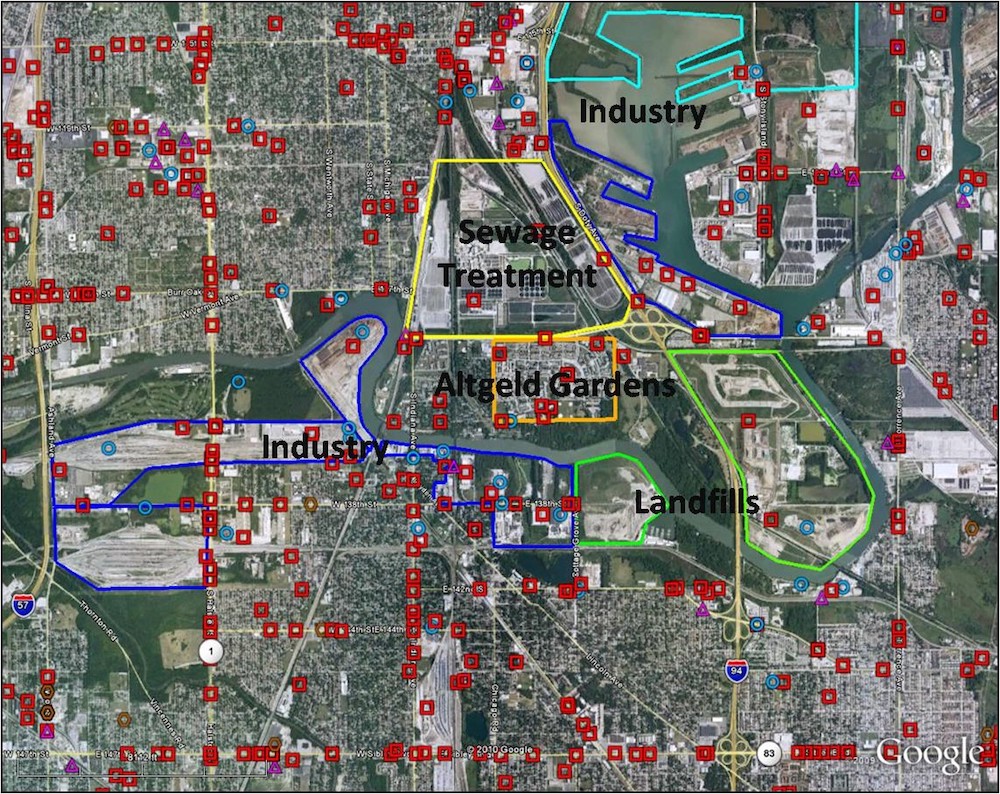

Altgeld Gardens is situated in the Calumet industrial area, with the Bishop Ford Freeway to the east, a sewage treatment center to the north and the Little Calumet River to the south. It is surrounded by abandoned industrial plants, hazardous waste sites and landfills. The housing project, initially touted as the "Garden Spot of America," was built on a former toxic dump site of the Pullman Rail Co.

It was, in Johnson's words, "a toxic doughnut."

"We're sitting in the center of it, and we are surrounded by all types of pollution," Hazel Johnson said in a 2009 interview with ChicagoTalks.org.

Altgeld Gardens, on the southeast end of Chicago, opened in 1945 as a public housing project for African American veterans returning from World War II and factory workers. It is ringed by industrial and landfill sites. (People for Community Recovery/Google Maps)

The groundbreaking 1987 United Church of Christ study on toxic sites and race identified 103 toxic waste sites in Chicago. The report concluded that nationwide, three out of five Black and Hispanic Americans lived in communities with abandoned toxic waste sites, and that race was the most significant determining factor for living near commercial hazardous waste facilities.

Johnson and her husband John did not know what lay in the land when they arrived in Chicago in the mid-1950s and moved to Altgeld Gardens in 1962. They came from New Orleans, where they met and where she grew up in the corridor of oil refineries and chemical companies known as "Cancer Alley."

Once in Chicago, the Johnson family grew, adding seven children. Cheryl Johnson remembers her mother as always being "a community-driven person." She planned summer activities for her children and other youth in the neighborhood, whether block parties, skating parties or regular trips to the Adventureland amusement park. Everyone called her "Mama Johnson" or "Mama Hazel."

In 1969, John Johnson died of lung cancer at age 41. Although he had been a light smoker, his early death shocked his wife, then 36. She also noticed her children had skin and respiratory ailments, and she heard from neighbors about other cancer cases in her community.

Ten years later, she began People for Community Recovery (PCR). Initially an avenue for residents to advocate for repairs in their community, the nonprofit soon shifted focus after Johnson heard of the deaths of four young girls from cancer and a TV news report that southeast Chicago had the highest cancer rate in the city and one of the highest in the nation.

Johnson became driven to find out what was happening.

At a local meeting with Environmental Protection Agency officials, her demands for answers were met with a health questionnaire to distribute. She proceeded to make 1,000 copies and circulate them around Altgeld. The responses reported back a range of cancer diagnoses and respiratory illnesses.

PCR, which incorporated in 1982, would partner with universities and hospitals to conduct more independent health surveys. One 1992-93 survey, conducted by the University of Illinois School of Public Health, found a high incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases like emphysema and chronic bronchitis, with a quarter of respondents reporting asthma. It also found that half of pregnancies resulted in either miscarriage, stillborn births or babies born prematurely or with birth defects.

PCR's research ultimately identified 50 landfills in the area, along with 250 leaking underground storage tanks and more than 350 hazardous waste sites.

"Her South Side community was like a postcard for environmental justice and racial justice," said Bullard, the distinguished professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University. "There was no separation."

Johnson and PCR took those findings to city leaders and health officials to press them to close down and clean up pollution sources affecting Altgeld Gardens. She attended community meetings and government hearings.

One protest in 1987 blocked CID Waste Management dump trucks from entering a landfill, while other actions tried to convince government officials to cancel permits for landfills and contaminated lagoons. They challenged the Chicago Housing Authority for its own pollution, use of asbestos and toxic dumping.

Altgeld Gardens housing units pictured Oct 11, 2008 (Flickr/Eric Allix Rogers)

Among the first big victories was in Maryland Manor, a nearby rural neighborhood where PCR got the city to install water and sewer lines. Residents had been paying for those services for 25 years, even though the lines did not exist.

"You could see the well water was visibly contaminated. And she just thought that it was inhumane for people to be living in this kind of condition and didn't have fresh water," said Cheryl Johnson, who worked alongside her mother at PCR and succeeded her as executive director in the early 2000s.

Other wins included the removal of asbestos and lead paint from housing complexes, securing training for local residents in lead abatement, and joining a coalition that successfully pushed for a moratorium on new or expanded landfills in the city of Chicago. In 2004, PCR helped reach a $10 million settlement with the Chicago Housing Authority over residents' exposure to PCBs and industrial pollutants; the money was credited to residents' rent. But Johnson "didn't look at [those] as victories or accomplishments," her daughter said. "She just felt like these are the things that make things right."

In many cases, Johnson was addressing issues before they had been named, whether food deserts, brownfields, spatial mismatch or climate change.

Johnson faced adversity at nearly every turn. She was called racist and derogatory names. Within her community, some saw her as seeking the spotlight, while others, struggling to get by, didn't have time to get involved. Politicians and other officials accused her of fabricating studies and statistics, questioned her education and called her a radical.

"They felt like a woman from public housing with seven kids should be worrying about her kids instead of talking about pollution in our area," said Cheryl Johnson.

In meetings, the elder Johnson was known for her "towering presence." A 1993 profile of her by the Los Angeles Times called her "a thorn in the side of the hazardous waste industry." Not one to raise her voice, she also didn't mince words.

David Pellow, who worked with PCR in the 1990s, recalled a meeting with state and federal EPA officials that was not going well. Community members sensed the government officials were there begrudgingly. Then Hazel Johnson spoke up and "very passionately and very powerfully" told the agencies they weren't doing enough and they needed to see the people as equal partners in the work.

"That was Hazel Johnson's way of saying, 'We may be from the southeast side of Chicago, we may be an under-resourced community and a marginalized population, but we are going to speak truth to power, we're going to speak plainly, and we're not going away,' " Pellow said.

![Cheryl Johnson, left, said it was her mother Hazel's "faith in God and her Catholic religion [that] kept our organization open" over its 40-plus years, and which kept her going through times of adversity. (Courtesy of People for Community Recovery) Cheryl Johnson, left, said it was her mother Hazel's "faith in God and her Catholic religion [that] kept our organization open" over its 40-plus years, and which kept her going through times of adversity. (Courtesy of People for Community Recovery)](/files/Image%20%2811%29%20Cheryl%20and%20Hazel%20Johnson%20c.jpg)

Cheryl Johnson, left, said it was her mother Hazel's "faith in God and her Catholic religion [that] kept our organization open" over its 40-plus years, and which kept her going through times of adversity. (Courtesy of People for Community Recovery)

Catholic faith 'kept her centered'

Throughout her life, Johnson's Catholic faith played an important role in her work.

"That was clearly something that motivated her and kept her centered and grounded," said Pellow, now chair of the environmental studies program at the University of California-Santa Barbara and director of its Global Environmental Justice Project.

In 1995, Hazel Johnson told the Chicago Tribune, "I definitely think I've been chosen by a higher power to do this work. Every day, I complain, protest and object, but it takes such vigilance and activism to keep legislators on their toes and government accountable to the people on environmental issues. I've been thrown in jail twice for getting in the way of big business, but I don't regret anything I've ever done, and I don't think I'll ever stop as long as I'm breathing."

The oldest of four siblings and the only one to live past their first birthday, she was raised Catholic, and at age 11, sent to a Catholic orphanage school after her mother became ill with tuberculosis, of which she died a year later. Her father, a truck driver, was often on the road and unable to take care of her.

Several years later, she left New Orleans with her aunt for California, where she attended Thomas Jefferson High School, in Los Angeles, through her sophomore year. It would be the highest level of education she completed. She returned to New Orleans and lived with her grandmother as she worked in a produce factory, where she met her husband.

When the couple moved to Chicago, she became a parishioner of Our Lady of the Garden Church, in Altgeld Gardens. She was active in the parish as a volunteer. As she supported its work, it supported hers, as the church was an early sponsor of PCR. After Our Lady of the Garden closed in 1993, she moved around to other parishes. Her funeral was held at St. Ailbe Catholic Church, several miles north of Altgeld.

Advertisement

Cheryl Johnson said it was her mother's "faith in God and her Catholic religion [that] kept our organization open" over its 40-plus years, and which kept her going through times of adversity. But while Catholicism was an important part of the elder Johnson's life, the feeling that she had been forced into the faith led her not to do the same with her own children, and she allowed them to make their own choices about religion.

The Catholic Church would provide an important point of connections throughout her life. For one, it helped introduce her to Obama, in his early 20s and a community organizer in Chicago working for Developing Communities Project, an extension of the Calumet Community Religious Conference, which consisted of predominantly Catholic churches.

It was at DePaul University's local Earth Summit where Pellow, then a student at Northwestern University, connected with PCR. A couple of years later, the organization led an environmental justice bus tour for DePaul students enrolled in environmental studies courses taught by Sylvia Hood Washington.

During that trip, Washington, who is Catholic, told Johnson about a film on environmental justice that she was producing for the Knights of Peter Claver and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Johnson offered her support and was later featured in the project.

Washington, an environmental epidemiologist and historian, went on to include the story of Johnson and PCR in the epilogue of her 2004 book Packing Them In: An Archeology of Environmental Racism in Chicago, 1865-1954.

To Washington, Johnson's Catholic faith was on display as she spoke against the degradation of human life in her community in a way that reflected a broader understanding of the pro-life concept.

"She had a very, in my opinion, an extremely pro-life stance, because she was not looking at just conception, because that was being violated there, but actually the degradation of the fetus if it survived conception," Washington said.

Friends and family described Johnson as a spiritual person whose faith helped form her sense of justice. Twenty years before Pope Francis released his encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," Johnson was using similar language to describe the environmental challenges facing the world.

"We have abused the planet mercilessly for years, and now we are paying the price," she told the Chicago Tribune in the 1995 interview. "If we want a safe environment for our children and grandchildren, we must clean up our act, no matter how hard a task it might be."

Hazel Johnson pictured outside of the White House in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy of People for Community Recovery)

Brushes with politics and presidents

As word of PCR's work spread, Johnson's gained a national profile both in the burgeoning environmental justice movement and in political circles.

In October 1991, she joined fellow frontline activists and community groups in Washington, D.C., for the first National People of Color Environmental Leadership summit. It was there they adopted 17 environmental justice principles, among them "the need for urban and rural ecological policies to clean up and rebuild our cities and rural areas in balance with nature, honoring the cultural integrity of all our communities, and providing fair access for all to the full range of resources."

It was also at the summit that Johnson first received the title of mother of the environmental justice movement. At the second People of Color summit, in 2002, Johnson was honored alongside 11 other women of color for their contributions to the movement. The accolades were a point of pride for Johnson, friends say, but she viewed them mostly as a way to leverage positive change for Altgeld Gardens and other environmentally impacted communities.

In June 1992, Johnson and Bullard joined an environmental justice delegation to the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro and participated in a panel, with Johnson representing the grassroots and Bullard the academic side. Even through translators, Johnson had a way of telling her story so people connected with it.

"Housing, issues around health, the issues around land use, issues around transportation, around jobs and employment, education — all of that. She could lay all of it out, and so that people could really understand it," said Bullard, who called her "an expert on her community."

Robert Bullard, the father of environmental justice, and Hazel Johnson, the mother of environmental justice, at the 2002 National People of Color Environmental Leadership summit in Washington, D.C. (Courtesy of Robert Bullard)

The two environmental justice trailblazers traveled together often, attending the World Congress against Racism, Rio+20 and U.N. climate summits. Along with Bullard, Johnson worked with former NAACP president Benjamin Chavis and other environmental justice leaders like Dana Austin and Beverly Wright. She made more trips to Washington to testify at congressional hearings and visit the White House.

In 1992, President George H.W. Bush presented Johnson with the EPA's Environment and Conservation Challenge Award, saying leaders like her "realize that the greening of America is truly a grassroots operation." As Cheryl Johnson tells it, after the ceremony the president whispered to her mother that he should have placed her in his Cabinet.

Two years later, Johnson was back at the White House with a group of environmental justice leaders to witness President Bill Clinton sign Executive Order 12898, which directed the EPA and federal government to identify at-risk communities and develop an environmental justice strategy.

Clinton invited Johnson back to the White House in 1996 for a ceremony honoring the country's top-100 environmental groups, with People for Community Recovery the lone grassroots Black organization among them. She'd later work on Al Gore's climate and environmental platform when the former vice president ran for president.

But the first U.S. president that Johnson met was not even a president yet.

When Obama was executive director of the Developing Communities Project, he worked with Johnson and other leaders in Altgeld Gardens to address the problems they faced. Cheryl Johnson remembers seeing Obama strategizing with her mother at the family's kitchen table numerous times, and her excitement when he told he had been accepted to Harvard Law School.

Obama's time as an organizer in Altgeld became a focal point of media coverage as his political career rose and he launched his presidential campaign in 2007. In his memoir, Dreams from My Father, the future president described how the Altgeld experience shaped him. But his decision to not name others, including Johnson, involved in a campaign to remove asbestos left some in the community feeling slighted.

That episode, along with Johnson's support for Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primary, led to a rift, Cheryl Johnson said. She told EarthBeat that her mother's support for Clinton was driven in part by the murder of Black leaders she had witnessed in the South, and that she feared for Obama, whom she saw like a son and for whom she voted in the general election. The pain from the ordeal stayed with her mother until her death, she added.

"She had not nothing but love for that man," Cheryl Johnson said.

Hazel Johnson, fifth from right, joins other environmental activists Feb. 16, 1994, in the Oval Office of the White House as President Bill Clinton signs Executive Order 12898, which directed the EPA and federal government to identify at-risk communities and develop an environmental justice strategy. (Courtesy of People for Community Recovery)

Local roots lead to national legacy

Ask what Johnson's impact on the environmental justice movement was, and you'll get numerous answers.

Some point to the way she linked eliminating pollution with the opportunity for economic development for people in her community. When PCR used a grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to train and certify people in lead abatement and hazardous waste removal, hundreds lined up to receive the training even though there was no promise of a job.

Some say it was her stamina to stay with the work even as solutions took time and new problems piled up. Others describe her ability to connect, rather than compartmentalize, issues like health, housing, energy, education and jobs and see them as related to environmental justice.

"I think that message is now is catching up with the work that she was doing 30 years ago," Bullard said.

To Washington, what makes Johnson stand out among the early pioneers of environmental justice was that she lived most of her life in the toxic environment she sought to clean up. "She was focused on equity and the right to be able to live in her community without being poisoned," she said.

That rooted experience is what led Johnson and other grassroots leaders to help define environmental justice and change the way the public defines the environment, added Pellow.

"It has to center [on] human beings."

Hazel Johnson's her name lives on in Altgeld Gardens. Along with the continuing work of PCR, a stretch of 130th Street is now called "Hazel Johnson EJ Way," and the Chicago Audubon Society named a piping plover chick after her last year.

Cheryl Johnson, center, and Hazel M. Johnson, right, are seen with Lisa P. Jackson, the first African American to serve as administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2009-2013). (Courtesy of People for Community Recovery)

Earlier in February, U.S. Rep. Bobby Rush, a longtime ally of Johnson's whose district includes Chicago's South Side, reintroduced legislation to recognize her contributions to environmental justice that would award her the Congressional Gold Medal, commission a commemorative stamp and designate April as the Hazel M. Johnson Environmental Justice Month.

Inside the White House today, President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris have made environmental justice a federal government priority, with a White House interagency council on environmental justice, along with new offices in the Justice Department and Department of Health and Human Services, as well as the one at the EPA. Biden has also directed government agencies to invest in disadvantaged areas that have been most impacted by pollution.

"It's not a footnote now. It's a headline," Bullard said. "Environmental justice has reached all the way up to the level where it's part of national policy across the board."

"[Hazel Johnson] would think it's about damn time, even though she wouldn't use 'damn,' " he added. "She would be the first to say, 'It's about time. You're very smart people, why are you just now getting to this?' This is what she had been saying for decades."

Pellow, the environmental justice project director at UC-Santa Barbara, added the Biden-Harris administration's embrace of an environmental and climate justice agenda exceeds what was achieved in the 1990s. And that is a sign that Johnson's legacy is living on.

At People for Community Recover, Cheryl Johnson and her staff see it as their mission to carry on her mother's work. They continue to lead toxic tours, though COVID-19 has suspended them for now. They are resisting a potential relocation of a General Iron scrap metal plant from Lincoln Park to the southeast side, which is now the focus of an EPA investigation. They are working with the Chicago Housing Authority to build a solar farm in their community. And they continue to wait for the government to complete cleanup of the former toxic waste dumps, as well as the nearby lagoons and Little Calumet River.

For Cheryl Johnson, seeing her mother receive a congressional medal and for it to be displayed in the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., would put environmental justice in its proper place. Ten years after her death, the life of Hazel Johnson remains an important story to tell, she said.

Added Washington, "For Catholics who have an interest in the environment and environmental justice, I think it's important for them to know that the mother of the environmental justice movement was Catholic."