Fire damage caused by the Glass Fire is seen Sept. 28 at Foothills Adventist Elementary school in Deer Park, California. (CNS/Fred Greaves, Reuters)

Climate change made a surprise appearance at the presidential debate on Tuesday night — for the first time since 2008 — even though it was not on the list of questions initially planned by moderator Chris Wallace of Fox News.

A poll by partners in the Covering Climate Now media consortium found that 72% of respondents wanted a climate question included in the presidential debates. And even before the debate, Joseph Winters at Grist argued that the other questions — including those related to the Supreme Court, the coronavirus pandemic and the economy — were also about climate.

"I was certainly glad it was asked, because I do think it's a very important to be addressed, not just for this election, but going forward," Dan Misleh, executive director of Catholic Climate Covenant, said of the question. "Scientists are telling us we need to get a handle on climate change or the planet is going to be in serious trouble, which obviously impacts people."

Nevertheless, he added, "The responses, if you could discern them through all the shouting back and forth, were fairly predictable."

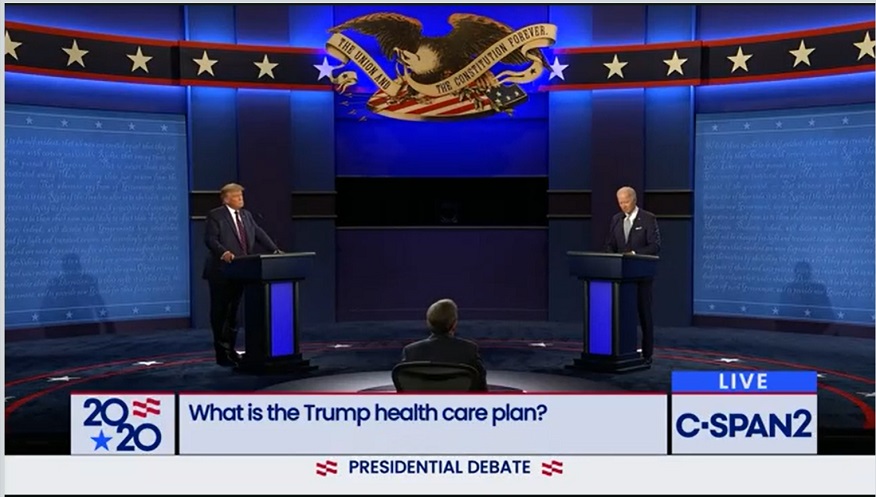

President Donald Trump, former Vice President Joe Biden and moderator Chris Wallace of Fox News are depicted during the Sept. 29 presidential debate. (NCR screenshot/C-SPAN)

The 10-minute segment, which came toward the end of the frequently acrimonious exchange between the candidates, gave Democrat Joe Biden a chance to list some of the proposals that are part of his campaign platform. It also elicited an admission from Republican President Donald Trump, who has said repeatedly that he doesn't know if climate change is "man-made," that human activities contribute to global warming "to an extent."

Following up on Trump's remark that he wanted "crystal clean water and air," another statement he has made repeatedly, Wallace asked the president about his record of pulling the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement on climate change — a decision due to take effect Nov. 4, the day after the election — and rolling back scores of environmental regulations enacted under the Obama administration.

Trump called the Paris Agreement a "disaster" for the U.S. and said the regulations were too costly. He also attributed forest fires raging in the western U.S. to poor forest management. Scientists have warned that rising temperatures and increased drought, which are linked to climate change, increase the likelihood of wildfires.

Although changes in forest- and fire-management policies could reduce the severity of California's wildfires, they will not eliminate them, writes James Temple in MIT Technology Review. And Trump's criticism of California's fire-control measures overlooked the fact that more than half of the forests in California are under federal, not state, government management.

Biden, who has pledged to return the U.S. to the Paris Agreement if he wins the election, pointed to the multibillion-dollar costs of flooding, hurricanes and rising sea levels and said his plan would create "millions of good-paying jobs … by having a new infrastructure that, in fact, is green."

He cited specifics, including switching to electric vehicles for the U.S. government, installing 500,000 vehicle charging stations and weatherizing 4 million buildings to increase energy efficiency.

Responding to criticism from Trump, he said his "Biden plan" was not the Green New Deal, the expansive framework on climate action proposed as a congressional resolution by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and Sen. Edward J. Markey of Massachusetts, both Democrats.

Both plans, however, offer a vision of a lower-carbon future.

Biden's "plan for a clean energy revolution and environmental justice" refers to climate change as a "climate emergency" and proposes a complete shift to a clean-energy economy and net-zero emissions by 2050. It calls for $1.7 million in federal spending over the next decade, including $400 billion on "clean energy research and innovation."

The funds would come from rollbacks of tax cuts for the wealthy enacted under the Trump administration, according to his plan, which also includes proposals for infrastructure, transportation and biodiversity conservation.

Biden has also pledged to work with states that have been continuing efforts to reduce their carbon footprints despite a lack of support from the federal government under Trump.

Advertisement

During the debate, Biden called for an international effort to slow deforestation in Brazil, suggesting that the U.S. and other countries pledge $20 billion for such an effort. Deforestation, mainly for ranching and agriculture, is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Amazonian countries.

The former vice president was mistaken, however, when he said that the Brazilian forest's capacity to absorb carbon dioxide exceeds U.S. emissions. The U.S. emits about 5 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide annually, while Brazilian climate scientist Carlos Nobre estimates that Amazonian forests now absorb less than 2 billion tons.

"What I seemed to take away from [the debate] was that [Biden] does believe that climate change is a serious issue that needs to be addressed" with both national and international action, Misleh said.

"On the international front, he believes strongly that If the U.S. is not engaged in [climate] negotiations, there is very little leverage that we'll have to move them in a direction that both the U.S. government and, more importantly, scientists think they need to go," he said.

Nevertheless, Misleh noted that one thing "conspicuously absent" from both the candidates' responses and Biden's climate plan is a price on carbon.

"If we don't put a price on the continuing burning of fossil fuels, then it's going to be much more difficult to reach some of these climate goals," he said. "There needs to be an incentive to do the right thing, and sometimes that's a disincentive, to [make people] stop doing the wrong thing."

[Barbara Fraser is NCR climate editor.]