(Left: Dreamstime/Bbsimpson; right: Dreamstime/Kenny Tong)

Editor's note: This is Part 2 of a two-part series on the Ceremony of the Red Heifer. Read Part 1 here: "With the red heifer ceremony, God purifies the people through the earth."

With the red heifer ceremony in the news, some Christians are learning how Jesus fulfilled this little known ancient ceremony in his passion. Servant of God Nicholas Black Elk, the great Lakota holy man and Catholic catechist, can help us further understand what this ceremony means.

The red heifer ceremony from the Book of Numbers — when a red heifer is sacrificially burned outside the Temple and her ashes are mixed with spring water to purify those made unclean by contact with death — has always been challenging to understand. King Solomon himself said he understood the entirety of the law except the ceremony of the red heifer.

Add to that historical confusion the current escalating conflict in the Middle East, plus the ceremony's connection to end of the world predictions, and the ceremony of the red heifer seems not only confusing, but also dangerous.

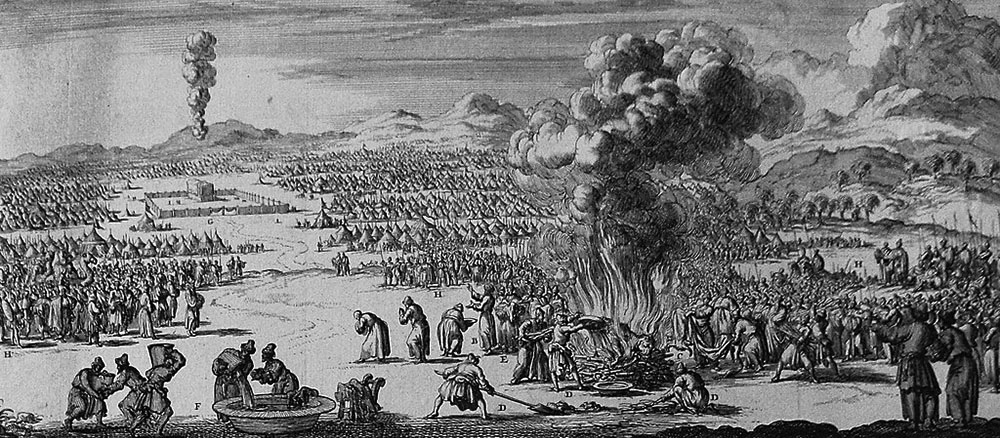

Purification by the red heifer (Numbers 19:1-10), depicted in a print from the Phillip Medhurst Collection of Bible illustrations (Wikimedia Commons/Philip De Vere, CC BY-SA 3.0)

While these perspectives are understandable, I also think the red heifer ceremony flows out of some of our deepest human spiritual instincts. Rituals that combine land, power and wholeness, where mystery is greater than clarity.

This makes sense from Indigenous perspectives, where holy people themselves often bridge the human, animal and divine. In the Lakota context, the most important spiritual figure is White Buffalo Woman, who brought the sacred pipe.

Chief Arvol Looking Horse, the 19th-generation keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Pipe, tells how White Buffalo Woman gave the pipe to the Lakota in a time of crisis.

The people forgot the ways of the Creator and the teachings of buffalo. The buffalo went away and the people faced starvation. White Buffalo Woman appeared as a sacred woman in white buckskin and gave the people a sacred bundle, which contained the pipe and seven ceremonies that will be revealed over time.

"Following the way of this sacred ca.nu.pa [pipe], you will walk in a sacred way upon the Earth," she said.

Advertisement

White Buffalo Woman departed. After walking a short distance, she crested a hill. Looking back, she rolled in the earth and became a young black buffalo. She rolled in the earth three more times, becoming a red buffalo, a yellow buckskin buffalo and finally a white buffalo.

Black Elk explains the meaning of this story in The Sacred Pipe. The pipe will be used in all the ceremonies and through it, "all these peoples, and all the things of the universe, are joined to you who smoke this pipe — all send their voices to Wakan-Tanka, the Great Spirit," he taught. "When you pray with this pipe, you pray for and with all things."

For Black Elk, the sacred pipe provides a cure for the people's alienation from the Creator and creation, a moral covenant that allows the people to flourish on the land, where "you will be bound to all your relatives."

The general thrust of White Buffalo Woman's teachings matches that of the Mosaic covenant: a moral covenant of right relationship that bestows the power to live and flourish on the land (i.e. "that you may live and prosper, and may have long life in the land" [Deuteronomy 5:33]). Interestingly, there is an important strand in Jewish tradition that portrays Moses with the horns of a wild ox, a kind of "buffalo man."

Jesus, like White Buffalo Woman, appeared among the people and gave seven sacred ceremonies — Catholics call them sacraments. Jesus also has a similar bovine nature.

Black Elk and other Catholics of his generation connected White Buffalo Woman to the Virgin Mary. This was not something initiated by the missionaries, but by the Lakota themselves.

"We say that we Christian women should be like her," Black Elk's daughter Lucy Looks Twice remembered. "Father [Eugene] Buechel accepted the Blessed Virgin as the same one who brought the pipe, and that was what we always thought."

Incidentally, the White Buffalo Woman/Virgin Mary connection came together in a person Black Elk would have known about, Mother Mary Catherine Ptesanwanyakapi (They See a White Buffalo Woman) (1867-93). She was the daughter of Joseph Crowfeather, a Hunkpapa Lakota chief, who was forced to carry the recently born Ptesanwanyakapi into battle to protect her. She became a Benedictine nun and prioress of the new American congregation.

Important here are the obvious parallels between White Buffalo Woman and the Virgin Mary's son. Jesus, like White Buffalo Woman, appeared among the people and gave seven sacred ceremonies — Catholics call them sacraments.

Jesus also has a similar bovine nature.

Traditionally, the red heifer ceremony was performed on the Mount of Olives, the location of the Garden of Gethsemane. There Jesus turned red by sweating blood in his agony. He, like the red heifer, suffered outside the camp (Hebrews 13:12), and the early church, from the Epistle of Barnabas to St. Augustine, interpreted Jesus as the red heifer.

Detail from a 15th-century German altarpiece depicting the Agony in the Garden (Wikimedia Commons/Txllxt TxllxT)

The bovine nature of Jesus' salvific power was something Black Elk saw in his visions before his Catholic baptism. In his Great Vision of the Sacred Tree when he was 9 years old, he saw a red man roll in the earth and become a buffalo, then roll again and became sacred medicine.

"The people shall follow the man's steps," Black Elk remembered in the 1931 interviews that became the basis of the book Black Elk Speaks. "Like him they shall walk and like the buffalo they shall live."

While dancing in the Ghost Dance in 1890, Black Elk saw the same red man, this time as Wanikiya, or "He Who Makes Live," which is the Lakota Catholic word for Christ. He had long hair, an eagle feather, pierced hands and was painted red.

When Wanikiya disappeared, the wind lifted Black Elk up and he flew over the renewed earth. "I could see plenty of meat there — buffalo all over," he recalled.

Seen through Black Elk's vision of Wanikiya — a red spirit who transformed into a buffalo and sacred medicine so that the people may live — the nature of Christ's salvific power in performing the red heifer ceremony makes more sense. Through sweating blood in his agony and immolating in his passion, he became Red Heifer Man and, like White Buffalo Woman, gave seven sacred ceremonies, or sacraments, the most important being the sacred medicine of his body.

Through White Buffalo Woman and Moses, the Creator gave sacred teachings and ceremonies that cultivated the power to flourish on Earth, that "the people may live."

Jesus, encountered by Black Elk in the Ghost Dance and in this later Catholic faith, drew on the moral covenants of White Buffalo Woman and Moses — right relationship that bestows the power to live and flourish on the land — and added a new regenerative power to it.

Jesus extends human flourishing on the land and the land itself beyond apparent limitations with divine power, not in spite of but through the power of the Earth. "He gave power to become children of God" (John 1:12), in other words, that "the people may live again."

Jesus, Red Heifer Man, have mercy on us, that the people may live.