The Baptismal font of St. Bartholomew Church in Liège, Belgium, carries the imagery of golden calves forward. Twelve bulls support the basin, where Christ stands in the waters of the Jordan, the power of the Holy Spirit rushing upon him (1 Samuel 16:13). (Wikimedia Commons/Jean-Pol Grandmont, CC by 2.5)

To empower eucharistic devotion, look to the golden calves.

No, not the golden calves installed by Jeroboam in 1 Kings 12:26-30. And definitely not the golden calf at Sinai — which Aaron created and the people worshiped when Moses lingered on the mountaintop with God (Exodus 32).

I'm talking about the 12, life-sized, bronze bulls in Solomon's Temple (Jeremiah 52:20). They faced outward, three toward each of the four cardinal directions, and supported a 16,000 gallon tank of water for ritual washing. Along with the horned altar of sacrifice, the 12 golden bulls were some of the most striking details dominating the courtyard, and they can help us understand the power of the Eucharist today.

Given the results of the golden calf incident at Sinai (it angered God), one wonders what Solomon, the world's wisest person (1 Kings 3:12), was thinking when he decided to install 12 golden cattle in the Temple. But Solomon had good reason for this choice.

The golden calf is more ambiguous than it first seems. Cattle had an enormous economic, cultural and spiritual role in biblical Israel. Most importantly, cattle were closely associated with God.

A common interpretation of the golden calf incident is that the Israelites reverted to one of the many Egyptian bull cults. With Moses unaccounted for and stranded in the wilderness, the people looked back to what they may have known in Egypt.

While the Israelites would have been familiar with Egyptian bull cults — and the centrality of cattle in the spiritual life of the entire Middle East at this time — a wholesale worship of a different god seems improbable given their sustained engagement with Yahweh. The Israelites could be childish and cranky, but they were not stupid.

More likely is that they used the golden calf to represent Yahweh, especially given God's close association with cattle. Or maybe the golden calf was a replacement for Moses, who like a bull, has been portrayed as horned. Since he was missing on the mountaintop, perhaps they felt they needed a new intermediary between God and the people.

Whatever the motivation of Aaron and the people, the problem has little or nothing to do with the fact that the statue they constructed was a bull, and more to do with their spiritual orientation toward it.

God once used a golden image of a serpent, arguably the most unambiguously negative animal in biblical tradition, to cure the people of snake poison (Numbers 21:9). If God can use a snake, then God can use a bull, especially given the repeated association of cattle imagery with God in the tradition.

"El" is the oldest name of God in the Bible. It had broad regional resonance in the Semitic world, and was unquestionably associated with cattle. Five times in the Old Testament the name "The Mighty One of Jacob" is used for God, which scholars such as Theodore J. Lewis argue is best translated as "The Bull of Jacob."

This connection might seem forced if not for the cultural context. The patriarchs, kings and prophets were constantly offering sacrifices of cattle, such as when David moved the ark (2 Samuel 6:13). After six steps, he sacrifices a bull and a fattened calf. Cattle were the highest form of sacrifice in the Law (Psalm 69:32).

The cultural and spiritual influence of cattle culminated in the horn as an image of royal and messianic power. Psalm 132 twice implores the Bull of Jacob to remember the Horn of David, and prophesies that a new horn will sprout.

Advertisement

St. Robert Bellarmine explains that the Old Testament use of the horn is taken "from horned animals, who use their horns for protection." "I will bring forth a horn to David," means for Bellarmine, "I will make David all powerful to conquer his enemies; like a rampant bull, with his horns full grown."

Horns were not just abstract and replaceable imagery, but essential in ceremonies that actualized God's power. Samuel anoints David with oil poured on him from a horn, the standard coronation ceremony (1 Samuel 16:13). It was then that the power of the Holy Spirit rushed upon him, evoking Psalm 92:11, "You have given me the strength of a wild ox; you have poured rich oil upon me" (New American Bible), or an even better translation, "But you have exalted my horn like that of the wild ox; you have poured over me fresh oil" (New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition).

This power is in turn embodied in the Temple, as the golden horns on the corners of the Altar of Sacrifice and Altar of Incense were considered their crowns.

The bulls of Solomon's Temple no doubt harken back to the 12 bulls sacrificed to ratify the Sinai Covenant, what Jesus evokes in his words of transubstantiation.

The bulls and horns of Solomon's Temple also point back to Eden. Scott Hahn argues that, the "Temple built by Solomon … was understood as a microcosm and embodiment of the very creation itself," a New Eden in that "the Temple plays the role of the garden. Zion and Eden have fused." This is seen in the "various Edenic motifs" in the Temple, priestly garments and liturgical furnishings, within which the bulls certainly fit. Cattle are specifically listed in Scripture as one type of living being created by God (Genesis 1:26, 28). More significantly, cattle are the first type of animal named by Adam (Genesis 2:20), reflecting the central role of cattle in the identity of the people.

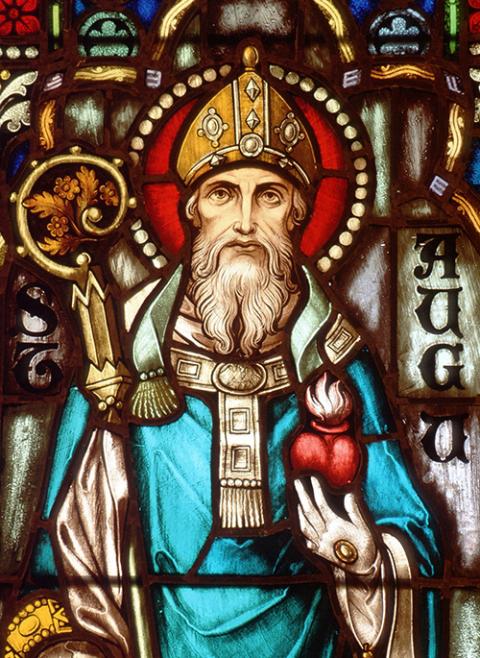

St. Augustine of Hippo, depicted in a stained-glass window in Crosier House in Phoenix, reminds us in the Liturgy of the Hours that "the Temple that Solomon built to the Lord was a type and figure of the future Church as well as the body of the Lord." (OSV News/Crosiers)

The Temple bulls described not only the character of the people, but with their placement marking the four directions and supporting the water basin, also suggested a prominent role in the nature of creation — their strength sustains the foundation of the world and radiates to the four corners.

The reason the Israelites associated God with cattle is power. Some of the most compelling teachings of Jesus are about power: "I lay down my life in order to take it up again. No one takes it from me, but I lay it down on my own. I have power to lay it down, and power to take it up again" (John 10:17-18); "He gave power to become children of God" (John 1:12).

Jesus' salvific power is well captured in the Horn of Salvation (Luke 1:69). What Bellarmine says of David is even more relevant for Jesus: "all powerful to conquer his enemies; like a rampant bull, with his horns full grown."

This constellation of power embodied in the golden calves of Solomon's Temple can help to fill one of the biggest vacuums in Eucharist devotion today. There is endless talk of "the power of the Eucharist." Yet I almost never hear anything about what this power is actually like. The little I do hear is awkward and unhelpful, such as, "The Eucharist is like an atom bomb." An atom bomb is certainly powerful, but a weapon of mass destruction is not only unbiblical, it's demonic.

The power of cattle is not only straight out of the tradition, it's also tangible and accessible. Go sit with the Yellowstone bison herd or one of the tribal herds that are expanding across North America, feel how they at once emerge from the land and envelop everything in their power, including — and especially — human beings.

Or go to a rodeo and sit in front. You'll be washed by the terror of the bull's raw power, previously unimaginable speed, size and strength. An infinitesimal fraction of the power of the Eucharist.