Detail view of the statue of St. Kateri Tekakwitha outside the Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi in Santa Fe. This depiction of the Algonquin-Mohawk maiden by Jemez sculptor Estella Loretto has features and ornamentation representative of the Pueblo people. (CNS/Nancy Wiechec)

Editor's note: EarthBeat is publishing a series of essays on the goals of the Laudato Si' Action Platform from speakers at the 2023 "Laudato Si' and the U.S. Catholic Church" conference, held virtually throughout June and July and co-sponsored by Creighton University and Catholic Climate Covenant. This essay is on the Laudato Si' Goal "Adoption of sustainable lifestyles."

For many Catholics, the 2015 publication of Pope Francis' encyclical "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" was a watershed moment. In it, Francis reminds us that care for the environment is an essential component of living the Catholic faith, which sparked conversations within and outside of the Catholic Church about the necessity of living sustainably and in communion with the natural world.

For me, the encyclical has also been an opportunity to explore the intersection of two important elements of my life: my Catholic faith and my experience as a Mohawk woman.

We cannot stop the climate crisis without confronting change within our hearts and habits, which can be challenging and inconvenient. Yet Laudato Si' is both an invitation to revolution as well as to stillness. We are called to quiet reflection and prayer alongside embracing that reformation.

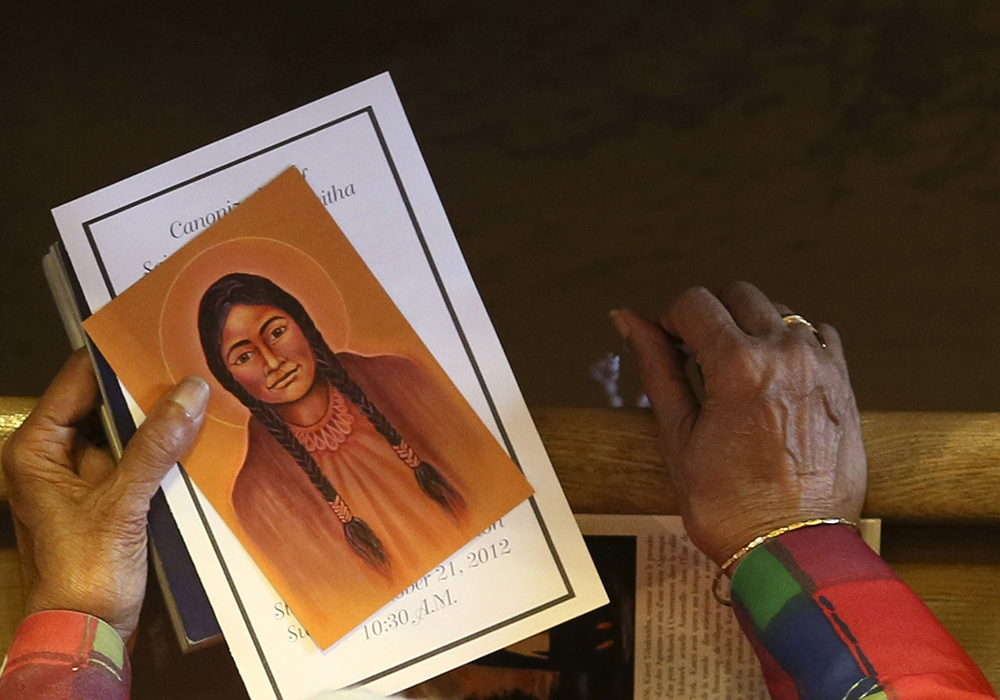

My family has a strong devotion to St. Kateri Tekakwitha, considered by many as one of the patron saints of ecology, who in 2012 was the first Indigenous woman to be canonized. I have always been inspired by Kateri's simple approach to life built around faith, nature and work. She models for us how the history, experience and knowledge of Indigenous peoples serve as critical points of engagement in the pursuit of faithful living and caring for our common home.

A woman holds a likeness of St. Kateri Tekakwitha — a 16th-century Mohawk-Algonquin woman known as the "Lily of the Mohawks" — during a special Mass commemorating her canonization at St. Francis Xavier Church, where she is buried, in Kahnawake, Quebec, Oct. 21, 2012. (CNS/Reuters/Christinne Musch)

Kateri was renowned in her village for her skillfulness at basket weaving and beading, and she also helped with cooking meals and collecting berries. She lived out her newfound Catholic faith quietly but firmly, keeping holy the Sabbath even though it was countercultural to do so amongst her traditional community. Kateri kept to an uncomplicated schedule, walking to church at regular intervals to pray and then returning to her family's lodge. She also fashioned a homemade oratory in the woods, securing a cross of sticks in the trunk of a tree by a stream for prayer when she could not attend Mass.

"We have forgotten that we ourselves are dust of the earth," Francis says in Laudato Si', "our very bodies are made up of her elements, we breathe her air and we receive life and refreshment from her waters."

Indeed, we have forgotten that we are part of the earth that God created — not just the planet Earth, but the specific land that we live on. But relationship with the land is at the core of Indigenous life and stewardship is a core value in the vast majority of Indigenous cultures. Strikingly, Native people make up less than 5% of the world's population, yet they steward and protect 80% of its biodiversity, according to National Geographic.

"[Indigenous peoples] are living in communion and harmony with the environment," Yon Fernández de Larrinoa, head of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization Indigenous Peoples Unit, said at the 2021 U.N. Climate Change Conference, COP26, in Glasgow, "and that's the only way to protect it in the long run."

Advertisement

The Haudenosaunee — a confederacy of six nations, including my and St. Kateri's Mohawk Nation — Iive in alignment with the Seventh Generation principle, which includes consideration of those who have not yet been born: "The nations of the Haudenosaunee believe that we borrow the earth from our children's children and it is our duty to protect it and the culture for future generations. All decisions made now are made with the future generations, who will inherit the earth, in mind."

This attention to passing on our world minimizes instant gratification decision-making that has a long-term impact on the environment and society. Francis sees the benefit of this, saying in Laudato Si', "Intergenerational solidarity is not optional, but rather a basic question of justice, since the world we have received also belongs to those who will follow us."

Learning deeply over time how to best care for the land they live on, Indigenous peoples also have a hyperlocal approach to the environment. They know how to use local resources efficiently, including a comprehensive understanding of foods that grow naturally in their communities without any intervention by humans. This prevents the soil, waters and inhabitants from becoming over burdened.

"Indigenous peoples are unique because they have a long-standing and intergenerational presence upon their traditional territories," wrote Rebecca Tsosie (Yaqui Nation), "and this 'ethics of place' is deeply embedded within their cultures and social organization."

Pictured are votive candles at the St. Kateri Tekakwitha shrine in Fonda, New York. (CNS file photo/Nancy Phelan Wiechec)

Kateri and Indigenous cultures teach us that we don't always need more and new technology to solve our current climate problems. The passing down of knowledge from countless generations is key to living in harmony with the land beneath our feet. Even if you have not lived in one place for generations, you can draw inspiration from Indigenous peoples by learning as much as possible about the land you now inhabit.

Here are some ideas to get started:

- Listen and learn from the original people who lived, and likely still live, where you are.

- Invest time and energy into your local environment.

- Research plants that are native to your region and make a goal to add them to your yard and to create a habitat for pollinators and other creatures.

- Think of the Seventh Generation principle when voting on new strategic plans for your town, or a new industry that may impact your local watershed.

- Live seasonally by growing your own vegetables or only purchasing what is in season.

- Pray outside and contemplate the tremendous goodness of God.

- Give thanks for this wondrous creation that supports us daily.