(Dreamstime/Syda Productions)

Editor's note: EarthBeat is publishing a series of essays on the goals of the Laudato Si' Action Platform from speakers at the 2023 "Laudato Si' and the U.S. Catholic Church" conference, held virtually throughout June and July and co-sponsored by Creighton University and Catholic Climate Covenant. This essay is on the Laudato Si' Goal "Ecological spirituality."

In the tradition of the Ignatian examen — a prayerful review of one's day taught by Ignatius of Loyola and generations of Jesuits since — I invite you to pause and consider the last 24 hours of your life. Review it and relive it chronologically, like a rewound tape played back, hour by hour or period by period: morning, afternoon, evening. What were you doing at each time of day? What were you thinking about while you were doing it? What were you feeling?

If you're continuing on to this paragraph without performing the examen, ask yourself why. If it's because you have an intrinsic resistance to following orders, especially when they come from strangers, then I'm sympathetic to you! If it's because you're in a rush, or because you aren't used to taking a contemplative breath (particularly while reading), observe whether that fits a pattern.

To make this an ecological examen, now ask: How much of the past day did you spend in touch with "the natural world"? At any point did you "consider the lilies of the field," an injunction Jesus probably meant not only as an instructive metaphor but as an invitation to an embodied practice? For how many of the last 24 hours were you outdoors? Did you encounter any nonhuman animals? Which of the world's textures did you feel against your skin?

Our built environments can block our vision of a greater horizon of connectedness to such an extent that 'the natural world' does seem to lie 'out there,' apart from us.

We're often hemmed in by walls and computer screens, by asphalt and concrete, and it is increasingly difficult to feel our connection to the "natural world." In fact, we aren't separate from the natural world; we're a part of it.

Yet our built environments can block our vision of a greater horizon of connectedness to such an extent that "the natural world" does seem to lie "out there," apart from us. It's a dualism that would have felt foreign to Jesus, who taught through parables rich in natural imagery, and to many of our own ancestors.

The Passionist priest Thomas Berry, who described himself as a "geologian," suggested that each of us has a "functional cosmology." Our cosmology is the story we believe about the history of the universe and our place in it; its functionality is the sway that story has on our lived experience.

It's easy for our ecological convictions to fall out of alignment with the way we function in the day to day. Losing a collective sense of our oneness with the rest of creation results in irrevocable damage to our planet. For instance, unsustainable forms of late capitalism and an implicit existential acceptance of our independence from the "natural world" (which Genesis 1:28 invites us to "fill" and "subdue") can be mutually enabling.

Advertisement

In the work I do with a faith-based organizing initiative that nurtures creation care teams in Catholic parishes, I've found that many people in the pews want to connect their contemporary ecological convictions to their ancient Catholic heritage and ancestry. Whether they use these words or not, they aspire to something on the scale of a new cosmology.

Pope Francis' 2015 encyclical, "Laudato Si', On Care for Our Common Home," provides just that: It rereads the Catholic tradition, from St. Francis of Assisi to the contemporary magisterium, through an eco-spiritual lens.

The encyclical suggests that while remaining Catholic, we can switch out a hierarchical image of God for a less dualistic and more immanent understanding of God present throughout, and sustaining, the whole web of life.

There are myriad ways we can embody this intellectual understanding and make it functional. We can connect with the spirit of our ancestors, whose humbling wisdom that all who live must die reminds us that the world doesn't revolve, literally or figuratively, around us.

Eco-spirituality invites us to radical transformation insofar as it demands that we learn from the Earth and not simply maintain our position of patriarchal dominance in 'protecting' it.

Spending time outside of built environments can also put our human existence into perspective. We can seed native plants in our gardens. We can employ less aggressively anthropocentric theological imagery.

While all of these spiritual choices can be authentic expressions of Catholicism, it is also true that eco-spirituality invites us to radical transformation insofar as it demands that we learn from the Earth and not simply maintain our position of patriarchal dominance in "protecting" it.

There is no limit to what the Earth and its varied species, metaphors and symbols can teach us about not only the beauty of mountains and forests, but life itself, death itself, materiality, deep time, ego. Our established ways of thinking and relating may get a little wilder and more expansive than the forms of belief our Roman institutions have handed down.

John the Evangelist writes, "I must decrease so that God might increase." Making our worldview less anthropocentric is as much about cutting our ego down to size — wherever ego can be found — as it is about going on a hike.

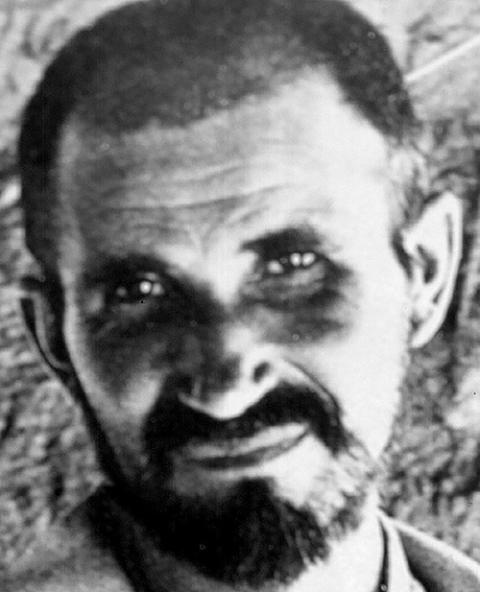

For instance, I was touched when Pope Francis canonized Br. Charles de Foucauld, who lived in the North African desert not as a missionary but as a contemplative and neighbor. Toward the end of his life, Charles was glad that he never converted a single soul but only witnessed, kindly, to human equality and fraternity.

With all due respect to Francis Xavier, it is significant that a church known for canonizing missionaries who baptized thousands with the sweep of an arm has bestowed that same recognition on someone who rejected the logic of religious conversion altogether.

It is a sign of a paradigm shift, a decentering of Christocentric hierarchies in favor of a radical belief that every person, regardless of religion, is already filled with the spirit of God. "The Lord is my shepherd and I lack nothing," the famous Psalm goes — whoever I am and whatever else I believe.

Such religious and epistemic humility should be common sense if we see creation as an interconnected web of dependence rather than as a competition to reach some evolutionary apogee (be it biological or religious). This may have been what the vast, otherworldly desert taught Brother Charles.

We've been socialized in many ways to the dualistic tendency to elevate ourselves over others. A vibrant eco-spirituality allows our expanded consciousness to derive wisdom, such as the truth of every created being's fundamental equality as imago Dei, from many experiential sources beyond the centers of human intellectual and ecclesiastical power.

This takes courage, whether we're afraid of excommunication or simply of being derided as "tree huggers," because it makes Mary's insistence that the powerful be cast from their thrones more than a pious prayer. But this is precisely what we need from spirituality today: a revision of paradigms that reinforce the illusion of our separateness, distribute power unevenly and enable the destruction of our common home.

Will tomorrow's examen find us a little more present to sources of wisdom that can nourish a courageous eco-spiritual Christianity?