(Unsplash/George Karelitsky)

The Navajo, or Diné, tell a story of how Turkey saved the People at the ending of one world and beginning of the next. Americans today can learn from this story, and from Turkey herself. It might even change the way we understand Thanksgiving.

The Diné tell of emerging from the earth through successive worlds on their creation journey: Black, Blue, Yellow, and then the current world, White Glittering. Sylvia Jackson provides a version of this story in Amá Sani dóó Achei Baahane, a collection of stories published by the Office of Diné Culture, Language and Community Services.

Yellow World was a beautiful, easy place to live. Coyote, the Trickster, ruined it. He stole the babies of Water Monster, who in response sent a massive flood. The People scattered in panic, trying to gather what they could. They fled to the highest mountain, where they escaped through a giant reed that reached to the clouds, bursting into a new world.

Turkey was last, her face red and sweaty. Running had never been easy for her with her short legs and big body. Turkey barely escaped, the foam of the torrent crashing against the tips of her tail feathers and staining them white.

When the People saw her, they burst out laughing and made fun of her. But then they looked around and saw the bleakness of the new world. It was an empty void with no living things, nothing like the Yellow world. The People lamented their haste and lack of foresight.

Then Turkey stood up and shook her feathers. Out of them fell all kinds of seeds: squash, beans, many varieties of corn. She was last because she had risked the flood to gather what the People needed.

Advertisement

The People repented and honored Turkey. First Woman "spoke in a very soft voice, 'I am sorry that I called Turkey 'lazy,' for he has brought us the very best things of all. When we reap our harvest we shall thank him for providing the seeds for our farms so we may have food for the winter months," goes the story as retold in Navajo Folk Tales, compiled by Franc Johnson Newcomb, a non-Indigenous teacher who worked with prominent Navajo medicine man Hosteen Klah to record traditional knowledge.

"All the First People willingly agreed with First Woman and they said to each other, 'From now on, Turkey shall be a very important person in our community for we will use his feathers in all our important ceremonies.' Then they called Turkey and decorated him with the colors of all the seeds he had brought from the lower world," Newcomb's compilation recounts. Now whenever anyone looks at Turkey, they will be reminded of Turkey's great gift of life.

I first learned about how Turkey saved the People in the weeks before Thanksgiving about a decade ago. We lived on the Navajo Nation, the largest Indian reservation in the U.S., located in Arizona, New Mexico and Utah.

Thanksgiving is a complex experience in Indigenous communities. The story of the First Thanksgiving has long been used to emphasize the erasure of Native communities and appropriation of land. In response, some Native people observe a Day of Mourning to commemorate the tragic history.

(Unsplash/Meelika Marzzarella)

I heard references to that at Thanksgiving time in Navajoland, but even more so, I heard jokes about the oddity of pilgrims and references to the story of Turkey.

Despite questions about how to be traditional people in a contemporary society, on a reservation with an area exceeding that of 10 states, there's a sense of cultural self-confidence that underlies everything — We're not going anywhere and what we know is as real as anything on the planet. Thanksgiving is absorbed into the Navajo world and not the other way around, captured in the name often used for the holiday, "T'azhii [Turkey] Day."

Turkey seemed to be everywhere. I heard about her from the mostly Navajo-speaking grandmother who babysat my son and from other residents in the sweat lodge. I borrowed Amá Sani dóó Achei Baahane from the Diné College Library and read the story over and over.

The story of how Turkey saved the People wasn't secret knowledge restricted to ceremony, but rather it infused the whole community in a matter-of-fact way and was the bedrock on which the overlay of Thanksgiving rested.

Maybe it was because of this Navajo cultural self-confidence that an extra layer of promise vibrated in the usual holiday buildup. Unlike most of the year, the sun didn’t bite, but instead was low and soft in the sky. Like in many communities across America, people began traveling home and preparing for family gatherings.

The feeling of movement seemed to be just as much about Turkey. Her story seemed to overflow the artificial reservation boundaries into the rest of America, illuminating the unexplained reasons why we do what we do at Thanksgiving.

Thanksgiving has a sacred yet deeply pluralist character. Regardless of what beliefs or values system one holds, many participate in a mass migration home for a ceremonial feast centered around Turkey and give, feel or at least are affected by gratitude. Living in Navajoland, it was easy to feel that Turkey played a role in this, that we gather to unknowingly celebrate her great gift of life and how she saved the People.

Benjamin Franklin, founding father and American renaissance man, seemed to sense this. He thought that the turkey could have been the United States' national bird. In a letter to his daughter, Sarah Bache, Franklin wrote that while the eagle is common throughout the world, the turkey is "a true original native of America." Though appearing a bit "vain and silly," the turkey is "a bird of courage, and would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British guards who should presume to invade his farm yard with a red coat on."

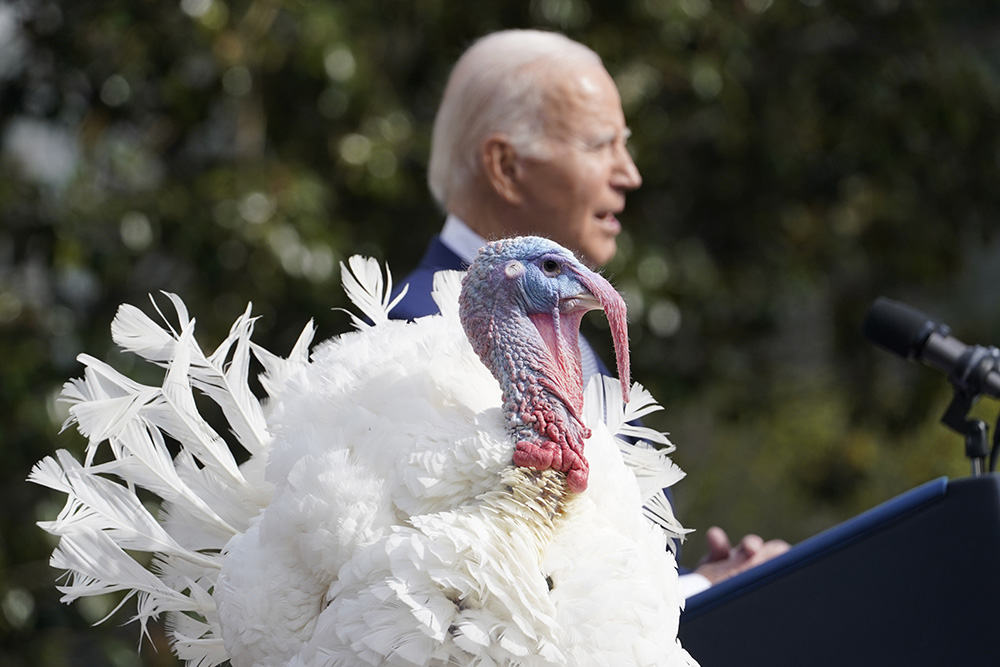

President Joe Biden pardons the national Thanksgiving turkeys, Liberty and Bell, during a ceremony on the South Lawn of the White House in Washington Nov. 20. (AP/Susan Walsh)

National birds and other such animal symbols exist to cultivate their virtues in us. Franklin rightly saw that turkey is resourceful, surprisingly fierce and lives in and is committed to community, cultivating in us connection, courage and resiliency — what the Navajo story portrays in fullness.

Yet at Thanksgiving, we eat Turkey. Many traditions, particularly Catholicism, have ceremonial feasts where you receive spiritual gifts through food, such as becoming part of the vast body of Christ by consuming the Eucharist.

What if through our ceremonial feast Turkey, in some way, bestows her power to renew the earth on us? She carries the seeds of the world as it was before the upheaval, seeds to be planted, from which a new beautiful world can take root.

Maybe we should all retell that story and give thanks for the continuing presence of the Navajo people and the gifts that their traditions carry.

Maybe the National Turkey Presentation, where the president ceremonially pardons Turkey, should incorporate a wild turkey and an Indigenous role, just as the Capitol Christmas Tree has in various years.

Despite what seems like growing upheaval in the world, it would help us to take hold of the seeds that Turkey carries in her feathers and be a part of cultivating new life, renewing our journey to become people for which the land gives thanks.