A statue on the grounds of the Seton Shrine near the historic Stone Farmhouse depicts St. Elizabeth Ann Seton catechizing children from “her rock” at the National Shrine Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes in Emmitsburg, Maryland. (Courtesy of Seton Shrine)

Mother Seton, looking over her rock from Corpus Christi Chapel, still sings to St. Mary's Mountain.

The National Shrine Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes in Emmitsburg, Maryland, sits on the side of St. Mary's Mountain and attracts more than 400,000 pilgrims a year. Though standing only 1,500 feet above sea level, the mountain's 1,000-foot prominence above the surrounding plain makes it stand out.

I know the grotto well, having gone to Mount St. Mary's University, which sits below the shrine. The grotto is part of the 1,300-acre campus, much of it on the mountain and preserved as forest.

As a student, I'd regularly climb the stairs to light candles and sometimes attend Mass at the shrine grotto, like one Easter when I stayed on campus to catch up on schoolwork. Other times I would wander the deer trails that spiderweb the mountain and lead to Indian Lookout, the north-facing vista that looks over Gettysburg and beyond.

When I recently returned to the mountain a couple days before Thanksgiving, it remained the quintessential Catholic shrine that I remembered: Stations of the Cross and icons winding through tall oaks, a 26-foot golden Mary towering over the canopy on a 78-foot campanile, and a view to the east that is, in the words of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, "half in the sky."

What struck me first during this recent visit was the global character of the grotto that has grown since I was a college student in the '90s. A large mosaic of the Virgin of Guadalupe now greets pilgrims at the entrance. Statues of Our Lady of Lavang of Vietnam; St. Pope John Paul II of Poland; and St. Mother Teresa of Kolkata, India, have joined the statuary. There even is an Eastern Rite saint, St. Sharbel, a Maronite monk and priest from Lebanon.

A statue of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton at the back of Corpus Christi Chapel overlooks "her rock" at the National Shrine Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes in Emmitsburg, Maryland. (Courtesy of the National Shrine Grotto)

I was also struck by the shrine's deep roots. Though named for Lourdes, I hadn't previously realized that the National Grotto predates that 1858 apparition by a half century. The replica Grotto of Lourdes was not built on the site until 1879.

The origin story of the Emmitsburg grotto is not a typical Marian apparition but a kind of epiphany through the land. The founder of Mount St. Mary's, Fr. John DuBois, was in the early 1800s walking through the mountain forest when he saw a flickering light. According to the grotto website, he found "amid the wild flowers, a stream that divided and flowed around a great oak where a recessed grotto had formed under the trunk. Here, he erected a rude cross."

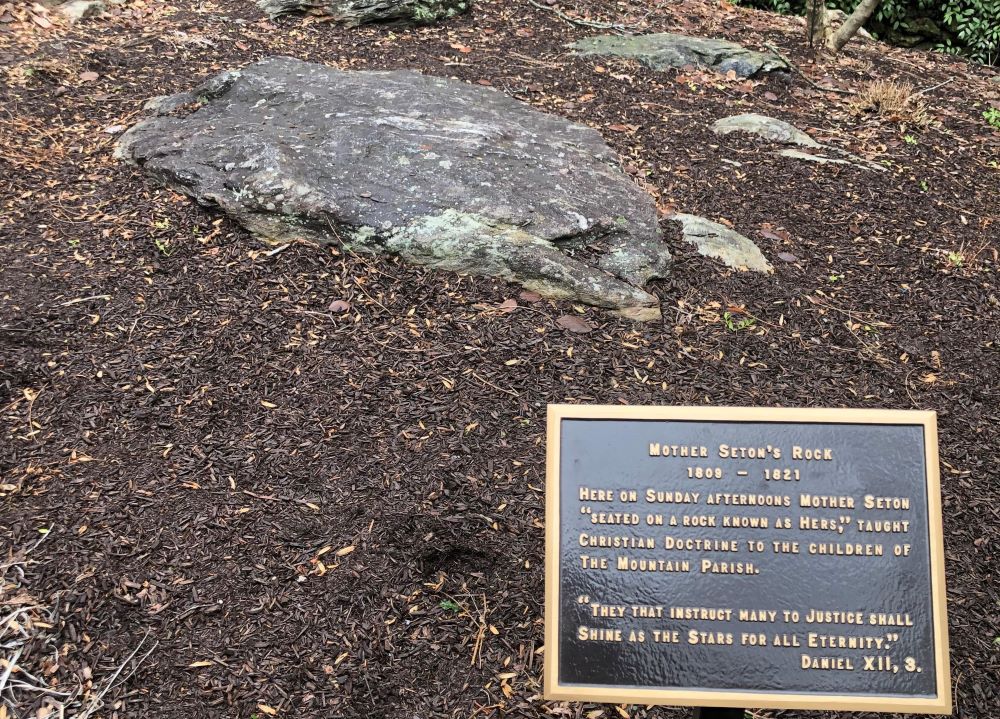

Still most intriguing to me upon this visit was perhaps the humblest part of the shrine: a weathered, gray rock near the holy spring, called "Mother Seton's Rock." A plaque explains that St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, the first American-born saint, sat on this rock on Sunday afternoons and taught the children.

Seton came to the grotto in 1809 when she moved to Emmitsburg to start the first United States women's religious order, the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph. She and the small group lived in a log cabin for six weeks.

Even when she moved into the completed motherhouse, Seton and the sisters provided music for Mass on the mountain every Sunday. Though a city girl from New York, she thrilled in the Sunday retreats, saying in her diary, "We would then quench our thirst from a neighboring spring and ramble for a time at the grotto, a wild and picturesque spot."

But the grotto's plaque is missing the best part of the story. According to Charles White, her first biographer, every time Seton sat down on her rock, she sang a song: "Benedicite, omnia opera Domini," or "Canticle of the Three Children." This passage, Daniel 3:57–87, is the canticle for morning prayer on the first and third Sundays, and for every important feast day. The canticle cycles through all of creation and calls on it to praise the Lord:

Mountains and hills, bless the Lord;

praise and exalt him above all forever …You springs, bless the Lord;

praise and exalt him above all forever (Daniel 3:75–77).

A plaque displayed at the National Shrine Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes in Emmitsburg, Maryland explains how St. Elizabeth Ann Seton would sit on "her rock" and teach the children. (Courtesy of the National Shrine Grotto)

The song at the grotto was not a small event but one of the high points of Seton's life, wrote White: "None that ever witnessed it could ever forget the tones of that voice and the fervor of that heart which, in the midst of the wild scenery of nature, called upon all creatures to bless and magnify their Creator."

Seton's tradition of praying with the mountain rock struck me as a poignant, under-appreciated ceremony that was a catalyst in her transformation because she created it during a critical time in her spiritual journey.

Seton came to the mountain as a widowed mother of five, the youngest only 7, a recent convert with the charge to create a religious order in the U.S. with a rule from Europe. In the midst of communal friction, spiritual dryness and waves of personal tragedy and suffering, she made the 2-mile journey up the mountain and sang the Benedicite, just as she sang hymns among the cedars and gazed at the constellation Orion as a teenager.

I see the mountain as an island refuge for Mother Seton, in part because it was for me. It held back the rising tide of "civilization" and stilled the buffeting of late adolescence, a spiritual director whose "conversation" distilled truth in the way Henry David Thoreau imagined a holy mountain could.

"It would be no small advantage if every college were thus located at the base of a mountain," Thoreau thought, "Every visit to its summit would, as it were, generalize the particular information gained below, and subject it to more catholic tests."

Advertisement

The mountain — the colors of winter dusk through the bare trees, the surrounding carpet of rocks, the way it cradled the dead in its arms, the pool of water shimmering in the mid-Atlantic heat, and a golden Blessed Mother that at once emerges from the mountain and is at one with it — took me outside myself and winnowed the chaff.

I learned about the "Canticle of the Three Children" at the Mount and though I could not sing it, thought of it as I wandered the trails, the mystery of all beings blessing the Lord. It was a way that I wanted to respond to the mountain and all its gifts, a faint echo of Seton's song.

In a 2020 interview with Catholic Review Radio, National Shrine Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes Director Dawn Walsh shared a story of a non-Catholic who explained why he regularly visits the grotto. "When I come to the Grotto," he said, "I feel the peace of all the prayers that have been prayed here before I arrived."

I think those prayers come not only from the pilgrims, but also from the mountain and Mother Seton, who upon her rock put them into words with her song.