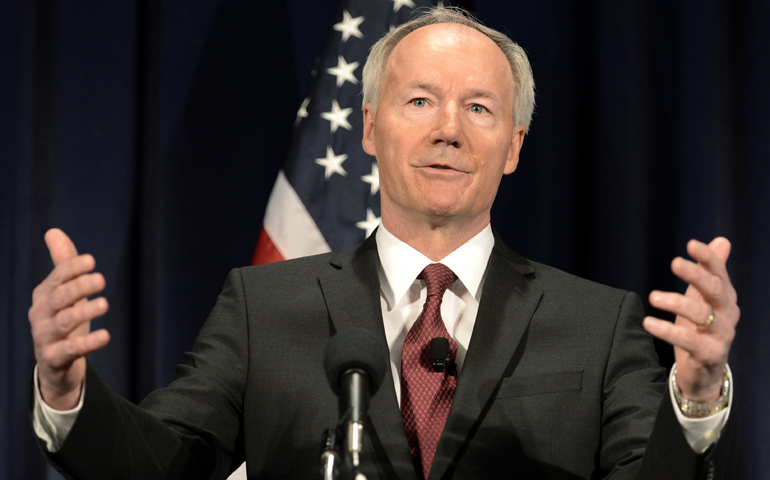

Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson is pictured in a 2013 photo. (CNS/Shawn Thew, EPA)

After Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson announced his intention to execute eight death row inmates in ten days later this month, lawyers, church officials and former correctional officers have been mobilizing.

Several court cases ranging from the county circuit court to the U.S. Supreme Court have stemmed from Hutchinson's signing of the eight death warrants in late February. If the executions — which are planned to take place between April 17-27 — continue as scheduled, it will be the highest rate of executions since the death penalty was reinstated nationally in 1976.

It will also mark the state's first execution since 2005. Executions were previously stalled due to litigations and difficulties obtaining the drugs necessary to the state's lethal injection protocol, according to The New York Times.

The unprecedented scheduling of two inmates per a day in the ten day period is a result of one of the state's lethal injection drugs expiring at the end of April. Arkansas' Department of Corrections uses a three injection drug protocol, with the first drug being midazolam, a sedative, central to several botched executions and court cases.

Lawyers for nine death row inmates, including the eight with signed death warrants, have been fighting against the use of this drug since 2015. The U.S. Supreme Court decided Feb. 21 to not hear arguments in Johnson v. Kelley, the case filed in October 2016 on behalf of the inmates. Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Stephen Breyer dissented.

Sotomayor wrote that she dissented for the same reasons she did in Arthur v. Dunn, a similar case where Alabama death row inmate Thomas Arthur challenged the state's usage of midazolam in its lethal injection protocol. The Supreme Court issued their refusal to hear Arthur v. Dunn the same day that the decision came down in Johnson v. Kelley.

Sotomayor, in her more thorough dissent in Arthur v. Dunn, wrote that midazolam "may turn out to be our most cruel experiment yet."

"Like a hangman's poorly tied noose or a malfunctioning electric chair, midazolam might render our latest method of execution too much for our conscience — and the Constitution — to bear," she wrote.

The U.S. flag flies in front of the Supreme Court in Washington in this file photo from May 18, 2015. (CNS/Joshua Roberts, Reuters)

Lawyers for the nine Arkansas inmates filed a re-hearing with the Supreme Court March 20, citing the expedited execution schedule as substantial reasoning for the judges to re-examine the case.

John Williams, the assistant federal defender in Arkansas' federal defender's office, felt strongly that "the schedule alone" is problematic.

"So not only is it a midazolam execution but it's an execution that is sped up to get rid of midazolam. That's really problematic in our minds," Williams told NCR.

Williams, who represents four of those scheduled for execution in April, says that statistically speaking, petitions for re-hearings aren't often granted. "However, we think these are pretty extraordinary circumstances," he said. "The way the state is going about it is pretty reckless, we think. So someone who wasn't convinced before may be convinced now."

The Supreme Court justices aren't conferencing the case until April 13, four days before the first set of scheduled executions.

Cruel and unusual punishment

Two lawsuits have also been filed with the Eastern District Court of Arkansas, one based on Arkansas' clemency process and another arguing that the scheduling violates the inmates' right against cruel and unusual punishment.

The case regarding clemency procedures has a hearing set for April 4. It claims that in the rush to execute inmates, the state is violating its own procedures. Williams said the case isn't about granting clemency but rather giving the parole board an adequate amount of time to consider the cases. According to Williams, the board is supposed to have a hearing at least 30 days before the execution date "so they can deliberate, make a ruling, give it to the governor."

"They're all crunched together so ... there's a high risk they become indistinct in the board's mind. Some of the hearings are on the same day, they've never done that before. What we're asking for is a schedule that would allow a more deliberative process for clemency and not a rush," Williams said.

As of April 4, the board has heard five clemency applications, with three negative recommendations from the board. The board will hear another application on Friday. Ultimately, the governor has the final say on whether a clemency is approved or denied.

The other court case — which will be heard April 10-12 —argues that the "state's unprecedented schedule of eight executions in a ten-day span amounts to cruel and unusual punishment, violates their [the inmates] right to counsel, and violates their right to access the courts and to counsel during the executions," according to a release from the legal practice Squire Patton Boggs.

The lawsuit also states that "any execution imposes an extraordinary amount of stress on corrections officers and others involved in the elaborate process" and that the multiple executions exasperates that stress, which "will accordingly increase the risk that the condemned inmate will suffer during the execution."

This argument has gained support from correctional officials across the U.S.

Twenty-five former correctional officials and administrators appealed March 29 to Hutchinson to reconsider the "pace of the planned executions."

The death chamber table is seen in 2010 at the state penitentiary in Huntsville, Texas. (CNS photo/courtesy Jenevieve Robbins, Texas Department of Criminal Justice handout via Reuters)

The letter talks about "The paradoxical nature of corrections officers' roles in an execution" noting that "officers who have dedicated their professional life to protecting the safety and wellbeing of prisoners are asked to participate in the execution of a person under their care."

Allen Ault, one of the letter's signatories, told NCR that the executions are not what correctional officers signed up for.

Ault, a former chief of the National Institute of Corrections and former corrections commissioner in Colorado, Georgia, and Mississippi, oversaw five executions and was the one who ordered the electrician to "pull the switch." Eventually it got to the point where he "just couldn't do it anymore."

He said he tried every rationalization he could think of to justify the executions and ease his conscience: maybe it would deter another violent crime or save just one future victim or possibly bring comfort to the victim's family — that perhaps, it would make capital punishment worthwhile. "But none of those worked. ... Just the logic of killing people to teach people not to kill people doesn't make any sense," Ault said.

Eventually Ault left corrections and sought treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder due to the executions. Ault knows of other officials who turned to alcohol or died by suicide.

"This [scheduling] seems to be without any thought of what that's going to do to those correctional officials. If [Hutchinison] is all fired to get this done, then I think he ought to go down and do it himself, but he won't. I've never had a politician, it's great to talk about how tough I am on crime and sign bills and death warrants, but they never get involved in the dirty work," Ault said.

The Association of U.S. Catholic Priests has also appealed to the governor, asking him to commute the death sentences to life in prison without parole. A letter from the nearly 1,200-member association states that "executions are a remnant of barbaric times which discredit our claim of being a civilized and humane society. Pope Francis and the U.S. Bishops have called for abolition of the death penalty. We stand with them."

Fr. Bob Bonnot, chair of the Association of U.S. Catholic Priests leadership team, told NCR that the scheduling makes the executions seem like a "spectacle."

"It's almost like a mania where we got to get this done and it's a short window so let's just execute eight guys in ten days. … It just strikes me as very unseemly, to put it mildly," Bonnot said.

Mental health issues raised

The Arkansas cases have also raised questions about inmate mental health and the constitutionality of executing individuals with mental illness.

The Fair Punishment Project issued a report March 30 alleging that at least five of the eight men to be executed appear to have a mental illness or intellectual impairment. Of the remaining three, one "endured shocking sexual and physical abuse" and two never received a proper mitigation investigation to determine if they had any illnesses or disabilities, the report says.

The report outlines the physical, mental and sexual abuse that five of the eight inmates endured during childhood. The report also claims that two of the inmates' lawyers faced their own mental illness or substance abuse.

While the report states that several inmates have shown symptoms of mental illness since childhood, it is unclear if the others showed signs of mental illness prior to or during their trial or if the illness developed post-conviction.

A lawsuit on behalf of Bruce Ward, one of the eight facing execution, opens with "Bruce Ward is a diagnosed schizophrenic with no rational understanding of his death sentence and impending execution." The lawsuit claims that Ward suffers from delusions, in which he believes "he will never receive the death penalty but will walk out of prison to great riches and public acclaim, including the Hollywood movie about the information he reveals." It also claims that he suffers from hallucinations where he hears "revelations from God."

The lawsuit also raises concerns about Ward's three decades serving in solitary confinement, which it said contributed to his deterioration and "constituted torture."

There is significant legal precedent against executing individuals with serious mental illness. In Ford v. Wainwright (1986) and Panetti v. Quarterman (2007), the Supreme Court affirmed that a death row prisoner must be aware of their pending execution and an understanding of why they are receiving the sentence at the time of their execution.

Just last month, the Supreme Court raised concerns of long-term sentences to solitary confinement, as well as executing intellectually disabled individuals.

Related: States debate death penalty issues (March 21, 2017)

In Ruiz v. Texas, death row inmate Rolando Ruiz appealed the Supreme Court to grant him a stay of execution based on the 22 years he spent on Texas' death row, predominantly in solitary confinement. Although the Supreme Court refused to grant Ruiz an 11th hour stay of execution and he was subsequently executed March 7, Breyer wrote a dissent, saying that Ruiz's claim "is a strong one, and we should consider it."

"If extended solitary confinement alone raises serious constitutional questions, then 20 years of solitary confinement, all the while under threat of execution, must raise similar questions, and to a rare degree, and with particular intensity," Breyer wrote.

On March 28 the U.S. Supreme Court sent a Texas death-row case back to lower courts, saying the inmate's intellectual disability should prevent his execution, according to Catholic News Service.

The court's 5-3 decision reversed a Texas appeals court ruling that said inmate Bobby James Moore was not intellectually disabled based on state criteria and could face execution.

"Texas cannot satisfactorily explain why it applies current medical standards for diagnosing intellectual disability in other contexts, yet clings to superseded standards when an individual's life is at stake," Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in the majority opinion.

Too few witnesses

If none of the court cases or appeals from correctional officers and Catholic priests stop the executions, one of the state's own rules just might.

Arkansas law requires at least six "respectable citizens" to witness each execution. Witnesses must be at least 21 years old and an Arkansas resident with no felony convictions. Victims' family members are not included in this count.

Though the state has said it can carry out these sentences on the dates set by the governor, there are signs of the state's desperation.

Arkansas' director of corrections used a March 21 address to the Little Rock Rotary Club to seek volunteer witnesses for the executions, according to a report on KARK-TV, an NBC affiliate in Little Rock.

Bill Booker, who as at the Rotary Club meeting, told the television station that members laughed at the request, thinking it was a joke. "It quickly became obvious that she was not kidding," he said.

Ault wasn't surprised about the state's difficulties. "I've talked to a lot of witnesses afterwards, and I mean, it was traumatic for them also and they weren't giving the orders to kill people. It isn't a pleasant experience," Ault said.

Williams said the difficulty finding witnesses could be "indicative" of a wider view about capital punishment.

"One could argue that if we're going to have a capital punishment system, it's something that shouldn't be hidden and it should be witnessed," he said. "If you don't have witnesses that want to go, what does that say about your capital punishment?"

[Kristen Whitney Daniels is an NCR Bertelsen intern. Catholic News Service contributed to this report.]

Editor's Note: The paragraph stating the number of clemency applications the parole board has heard has been updated to reflect the latest information on April 4 at 2 p.m. CST.