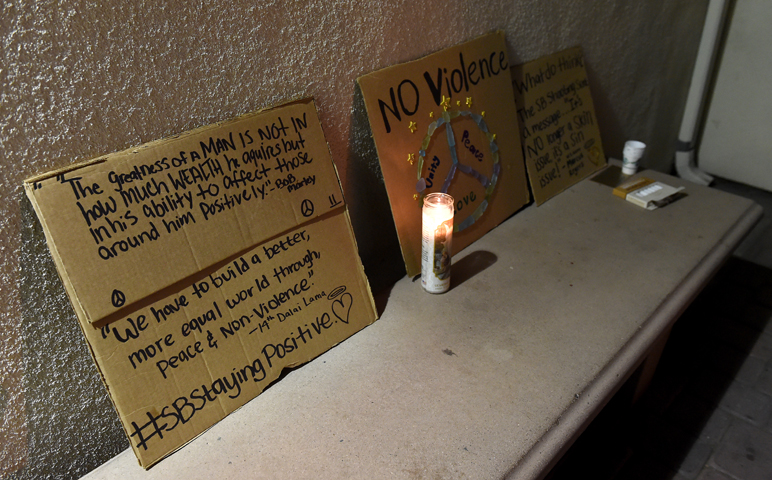

A memorial outside Our Lady of the Rosary Cathedral in San Bernardino, Calif., in memory of the victims killed in a mass shooting Dec. 2. (CNS/Jennifer Cappuccio Maher, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin)

As Jews around the world finished celebrating Hanukkah and Christians journey toward the Star of Bethlehem, this sacred season of light again struggles with shadows.

Terrorist attacks in Paris, the shooting at a Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado and the massacre in San Bernardino leave many angry, numb and insecure. A billionaire demagogue -- toxic political talents honed for our reality TV culture -- leads the Republican primary for the most powerful office in the world. Stoking economic and racial resentment, Trump's strongman swagger includes promises of an impenetrable border wall and a ban on Muslims entering the country. Americans are alternatively horrified and repelled, reassured and entranced.

The president of Liberty University urges his Christian students to arm themselves in order to "end those Muslims before they walk in and kill." A renowned pediatric neurosurgeon running for the White House compares refugees to "rabid dogs." More than 30 governors have pledged to slam the door on families fleeing violence and death in Syria. Twelve thousand displaced people are stranded in the desert between Syria and Jordan. In another desert town, Christian evangelical Sen. Ted Cruz grins into the gaudy Las Vegas lights and pledges to "carpet bomb" terrorists into oblivion, doubling down on his promise to find out if "sand can glow." The "pro-life" Texas senator waves off concerns about the death of innocents in such a campaign and rails against "political correctness" in foreign policy. The candidates show few signs of struggling with how their Christian faith and frequent appeals to family values square with proposals to turn away the most vulnerable. Never mind that Mary, Joseph and Jesus were refugees who crossed a border in flight from a murderous leader. Small detail, it seems, on the way to winning the party's nomination for president.

Related: Editorial: Fear of refugees is unworthy of American ideals

Confronted with the existential threat of terrorism, shameful political fear mongering and the disorienting din of a 24-hour news cycle, the instinct to hunker down and hold tight to our ideologies, possessions and prejudices may be easy to understand. Lock the door. Turn out the lights. Buy a gun.

Facing Chaos in a Year of Mercy

The Christian path is more hopeful, and a harder journey.

The Jesus we met in the Gospels is always pulling the motley crew of humanity he meets beyond themselves, out of fear, away from comfort zones. He upends societal norms and expectations. At times, his lessons seem irrational. Love your enemies. Why? What does this even mean? In the war-torn Central African Republic last month, where Muslims and Christian militias have battled in a civil war, Pope Francis insisted that one of the "essential characteristics" of being a Christian is a love of enemies, "which protects us from the temptation to seek revenge and from the spiral of endless retaliation." He held up "practitioners of forgiveness, specialists in reconciliation, experts in mercy" in contrast to those who wield "instruments of death."

As the Catholic church begins a Jubilee Year of Mercy, it's worth thinking about what mercy means in an age of terror, and in the face of a creeping darkness in our political mood. Some might dismiss mercy as soft or saccharine. You might caricature it as a Hallmark card virtue, anodyne and easily overlooked. This is a mistake. As German Cardinal Walter Kasper describes it in the title of his book, mercy is the "essence of the Gospel and the key to Christian life." Mercy has a particular meaning and application when it comes to sacramental questions. Boisterous debates over whether the church should do more to welcome back divorced and remarried Catholics who are denied Communion divided cardinals at the last two Synods at the Vatican.

Well beyond ecclesial life, there is a politics of mercy deeply connected to justice and the common good. Mercy is not blind to the ways social structures can diminish human dignity and perpetuate inequality. Mass incarceration, environmental devastation, racism and an "economy of exclusion" should compel us to grapple with mercy not as an abstract ideal or a high-brow theological concept, but as something tangible and gritty that requires individual and collective action. The great moral leaders and prophets have always known this. Being a disciple of mercy is countercultural. Dorothy Day fed the hungry but also questioned why so many were poor, and she risked her reputation protesting war, the draft and standing up for conscientious objection even when religious and political elites balked. Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and other less celebrated activists in the civil rights movement knew they risked assassination because of their commitment to mercy and justice. The shadow of death did not stop them. King took his place among the centuries of Christian martyrs.

Pope Francis, as usual, has a knack for explaining the essence of mercy better than most. He even coined a new word in Spanish – misercordiando. Mercy-ing in English. In this way, mercy is not just an object, a static noun, but an active verb signifying motion. Mercy requires leaving the safe place, confronting complexity, even facing evil. The Christian doesn't travel this hard path alone. We believe that "the light shines in the darkness and the darkness has not overcome it," as we read in the Gospel of John. None of this gives us easy answers for how to make sense of senseless gun violence, radical extremism or craven politicians who exploit fear.

But for those of us preparing for the Prince of Peace, a savior born in a dusty outpost of the Roman Empire, we take hope in a God who is so close to us that he took on the form of a slave and experienced joy, doubt, suffering, death. The Word is made Flesh, and in the Incarnation we experience the divine not as a distant abstraction but as an encounter with a person, and with each other. People of faith need not be naïve to the real dangers of the world, or blind to the hypocrisy and cowardice of many who act in the name of religion, to find strength in a God who is closest to the refugee, the woman widowed by a drone attack, the peaceful Muslim targeted for his faith.

After the San Bernardino shootings that killed 14 people, the New York Daily News ran a provocative front-page story with the headline, "God Isn't Fixing This." The headline and the first line in the article -- "Prayers aren't working" -- correctly observed that more pious platitudes were not enough to prevent another act of gun violence. A predictable flare up in the culture wars ensued over social media as people defending prayer traded barbs with those who cheered the newspaper's call for action. The false choice of pitting prayer against action, of course, is nonsense. Prayer can deepen a commitment to social transformation, and has always been interwoven into historic struggles for justice. "To clasp the hands in prayer," the Protestant theologian Karl Barth observed, "is the beginning of an uprising against the disorder of the world."

Prayer and mercy are not cheap dates. Both require hard work, struggles. Christ enters the world amid chaos, violence and fear. We sanitize the stable in Bethlehem, and domesticate the Gospel by smoothing out its radical edges. In this holy season, the sacred and profane, as always, are never far apart. We reach the light by walking through darkness.

[John Gehring is Catholic Program Director at Faith in Public Life. He is author of The Francis Effect: A Radical Pope's Challenge to the American Catholic Church.]