St. John's Ballymaghery Church near Hilltown, Northern Ireland, where accused abuser Fr. Malachy Finegan once served (Claude Colart)

Clerical abuse survivors and their advocates are criticizing a new redress scheme in a Northern Irish diocese that has placed a cap on payments for victims.

They say that while the scheme offers to pay about $106,000 to individual survivors, from a total purse of some $3.4 million, limiting the compensation was insensitive and unjust.

Some suggest the scheme from the Dromore Diocese would likely suit victims of potential grooming, but are advising other survivors to avoid using it.

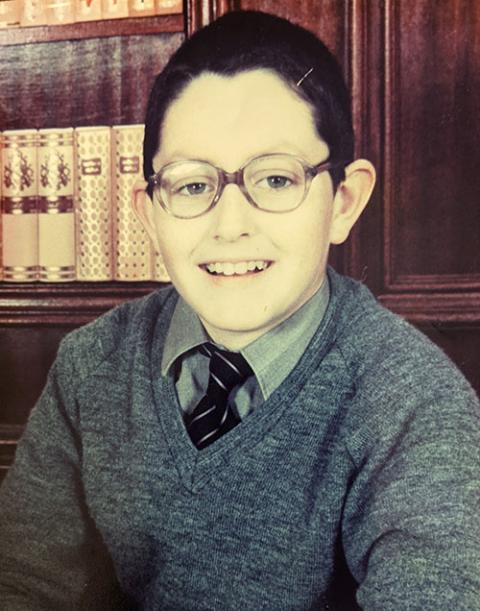

Sean Faloon, who says he was sexually abused by Fr. Malachy Finegan for eight years from the age of 10, expressed outrage to NCR.

"You can't put a cap on trauma," said Faloon, who estimates that Finegan abused him at least 350 times, including in the two churches where Finegan was parish priest, St. John's Ballymaghery and St. John's Ballygorian, both part of Clonduff Parish in Hilltown.

Sean Faloon at age 11 (Courtesy of Sean Faloon)

"Too many people knew what Finegan was. Instead of protecting someone like me, they decided to protect a pedophile," he said.

Faloon wants the prosecution of those who enabled Finegan to continue his crimes.

Both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland have been dealing with devastating reports of abuse in recent decades. This latest scheme was announced by Archbishop Eamon Martin of Armagh, Northern Ireland, on Sept. 29.

Martin, who as the primate of all Ireland is traditionally seen as the highest Catholic representative across Ireland, is serving as apostolic administrator of Dromore.

The last resident bishop of Dromore, John McAreavey, resigned under a cloud in 2018 after news reports that he had celebrated the funeral Mass in 2002 for Finegan, despite knowing at the time of claims against the priest.

In fact, as early as 1994, the diocese sent Finegan to Our Lady of Victory rehabilitation center near Stroud, in England, after receiving a complaint of abuse. Parishioners then believed the priest was in Spain recovering from hip surgery.

While Finegan was away, he regularly called a parishioner in Hilltown who summoned Faloon to the phone in her hallway to speak with Finegan.

Now aged 42 and living in Perth, Scotland, Faloon believes the conversations about school and sport, interspersed with sexually charged questions, were to assess if he had said anything about the abuse, something Finegan had long told him would "ruin" both of them.

At a cost of $40,000 Finegan's therapy was to last seven months but after just four, he returned to Clonduff Parish and continued abusing Faloon.

Finegan died in 2002 without ever having been questioned or prosecuted.

Martin has confirmed that the Dromore Diocese had received at least 70 allegations of sexual abuse committed by priests over 35 years. At least 40 cases are said to involve Finegan.

Announcing the scheme on Sept. 29, he apologized to survivors and called the abuse "abhorrent, inexcusable and indefensible."

The Dromore Diocese did not respond to questions from NCR about survivors' concerns over the new redress scheme's payment cap, instead referring the publication only to the diocese's previous press release.

Advertisement

Faloon's Belfast-based lawyer, Kevin Winters, recently filed a complaint with England's Gloucestershire Police, which has since appointed a senior detective to determine if the therapy center, which closed in 2004, should be investigated.

Winters welcomed the scheme as "positive" and said he had already signed up a number of his clients. But he felt that capping compensation was "mercenary and crass."

The $109,000 limit would suit survivors who had endured "potential grooming" by priests, he said, but where sexual abuse was the "starting point," those should be dealt with by outside redress.

"I think the church lost an opportunity here," he told NCR. "The goodwill attached to Eamon Martin's announcement has been eroded somewhat by these two key financial figures."

Winters, who met Martin a few weeks ago with a survivor, believes the archbishop "genuinely" wants to act on clerical sexual abuse, but the lawyer said the payment cap would be ineffectual.

"If the pot runs out, there's going to have to be legal ways of accessing additional assets," Winters said. "You can pursue the church and get it to come up with the money. And if you look at the Catholic Church as a corporate structure, it has a chairman at the head of it in Rome."

Faloon reported the abuse to his doctor in 1996, and then to police. Nine individuals were interviewed, but no one was prosecuted, he said.

He sued the Dromore Diocese after the breaking of agreements he made with Bishop Francis Brooks and later McAreavey that Finegan should not be permitted near children or allowed to celebrate Mass, he said.

Many of the complaints against Finegan come from when he worked at, or was president of, the prestigious St. Colman's College, a school for boys in Newry, established in 1823 as the Dromore Diocesan Seminary.

St. Colman's College in Newry, Northern Ireland (Claude Colart)

When the diocese settled a case in favor of a former St. Colman's pupil in 2017, the college condemned the abuse and said it had removed from display all photographs of Finegan.

Winters, who attended the college from the late 1970s to the early 1980s, believes he was also the victim of attempted grooming which he said happened there "on an industrial scale."

In 1970, 19 years before he began abusing Faloon, Finegan met 11-year-old Tony Gribben, a first-year student and a monthly boarder.

A scholarship boy, and the sixth youngest in a conservative family of seven children, whose proud parents hoped he would take up the priesthood, Gribben's life changed suddenly and dramatically.

One day in Latin class, Finegan struck him hard across the side of his head leaving him "seeing stars." The blow was so severe he felt as if he almost lost consciousness.

"I was shocked, humiliated in front of the rest of the class," said Gribben in a conversation from his home in Turin, Italy. Corporal punishment was the norm at the school but he assumes this was the first step in breaking him down.

Within weeks the physical abuse became sexual and when Gribben reached puberty, "serious sexual assaults" by Finegan became regular, he said.

He never considered confiding in anyone, not least fellow pupils in the college's atmosphere of fear and secrecy. "I was aware that other people knew what was going on but didn't ask questions," he said.

It was only in 2018 that Gribben realized there "were things I need to resolve in my life" and told two of his siblings and the police.

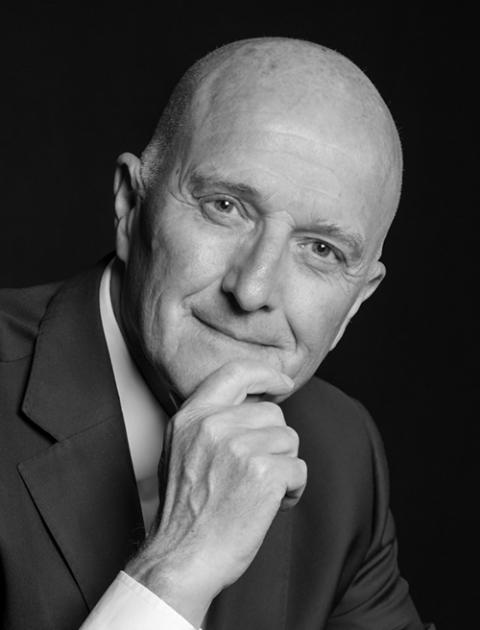

Tony Gribben (Courtesy of Tony Gribben)

"We keep forgetting about the whole impact on families," said Gribben, who said his family split apart when he went public.

Inspired by Faloon's courage in taking legal action against the Dromore Diocese, he began his own, and in June, a week before he turned 62, he was awarded a six-figure sum.

Gribben met Martin on Aug. 26, and the archbishop apologized to the victim for the abuse he suffered. Gribben said the encounter "did help" but that he also told the prelate that "only an independent public inquiry into Finegan's abuse" would satisfy him.

For Gribben, the redress scheme "could be considered by people who would have suffered lower forms of abuse, like grooming, inappropriate conversation or maybe light touching."

He advises anyone who has suffered "anything more serious" not even to consider it.

"Most people who come forward with disclosure want justice; they're not interested in money," he said.

Close to retirement, Gribben spends much of his free time meeting online with a group of survivors and speaking to others, some of whom he describes as "very broken."

One man in his group is a 72-year-old who says Finegan abused him when he was a child at a rural parish church in County Armagh in 1961.

Gribben links the church's inaction on Finegan to effectively allowing what became a litany of abuse across generations.

"Had someone stepped in earlier on Finegan in the '60s and '70s, we wouldn't be where we are today in terms of talking about a redress scheme," he said. "Certainly, we wouldn't have the number of people whose lives have been destroyed."

[Sahm Venter is a freelance journalist and the editor of several books, including The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela.]