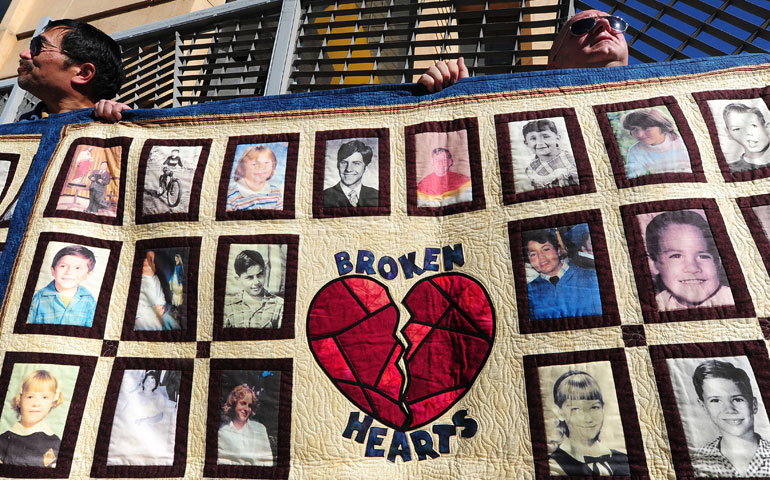

Abuse victim Jorgen Olsen, right, and supporter Glenn Gorospa hold quilts bearing portraits of abused children while gathered outside the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles Feb. 1. (AFP PHOTO/Frederic J. BROWN)

Way back in 2004, in the early days of the seemingly endless struggle for justice by the victims of several priests from Los Angeles, I had a conversation with one of the attorneys who represented several of these men and women. He said, "By the time this is over we are going to find out just how much Roger Mahony's cardinal hat is worth." I suspect that neither of us realized that this was truly a prophetic statement. In the end, the cost was calculated in dollars, trust, respect and faith.

The cost must also include the loss of truth.

The media responses to the final order to disclose all the files of predator priests and descriptions of the 10-year saga that preceded the court's decision on Jan. 31 do not come close to telling the full story of the nightmare that led up to that day. The last major act, Archbishop Jose Gomez's meaningless censure of Mahony and Mahony's whining retort on his blog, is all about them and not about the real core of this almost incredible decade of events. At the heart of it all are the victims of Los Angeles priests, several hundred men and women. Yet the legal battle that went on and on not only overlooked them but continued to heap pain on their already scarred souls.

The media could not possibly recount the massive toll this took on so many people. The price of Mahony's red hat is certainly steep in dollars. He retained an army of expensive lawyers to defend his intentional mishandling of reports of sexual abuse, and then to create legal roadblocks to the disclosure of the culprits' files. The real cost of his hat was in people.

There were 508 victim/survivors as plaintiffs in the cases that eventually were settled in 2007 for $660 million. They had been put through agony during the months and years they were manipulated, lied to and revictimized before any of them went to court. Then the first phase of the nightmare began.

The settlement process was long, tedious and so byzantine that no one could possibly describe it with any accuracy. All the while, the lawyers retained by the cardinal were doing their utmost to prolong anything resembling a just solution. When the bishops' cheerleaders throughout the country accuse the victims' lawyers of being greedy, they should take another look at the dozens of attorneys who made up Mahony's brigade, all of whom were high-priced and none of whom worked pro bono for even an hour. Whenever the cardinal appeared for a deposition or meeting involving the cases, at least six and often 10 lawyers accompanied him. Who paid the legal fees? The "people of God" of the Los Angeles archdiocese. Who else?

How many of these people of God could have benefitted from the money diverted to the lawyers and to the public relations firm as well? We will never know.

The process took its toll not only on the victims but on their lawyers, all of whom were working on contingency, which meant they were looking at financial doom if the whole venture fell through. They worked far above and beyond what was required for what they earned. Some were so disgusted with the never-ending antics of the church in court and at the mediation table that they left the practice of law when it was all over. A number who had at one time been practicing Catholics lost all respect and trust in the institutional church. One lawyer spoke up at a gathering after the settlement and said, "I don't believe in God anymore." This man had not only represented victims in Los Angeles and elsewhere for years, but he had provided for many the emotional and spiritual support so essential after their experiences with the church. He told me once that he had to make 70 cross-country plane trips to Los Angeles for the case.

As part of the 2007 settlement, the archdiocese agreed to disclose the files of the perpetrators. The ink was not dry on the settlement before the cardinal launched what would become a seemingly endless series of legal objections and procedural delays that at one point went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The core of Mahony's legal claim to prevent the disclosure of what he had already agreed to was the idea that all communications between a priest and his bishop are privileged in the sense that they cannot be disclosed without violating the First Amendment. He and his legal crew based this on what they called the "formation privilege." Priests are always in formation and their bishop is like their father, guiding and teaching them along the way, or so their story goes.

The Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office asked me to write a declaration in support of their request to get the files. I did and in it I presented documentary evidence that the "formation privilege" was a fiction of the cardinal's imagination with no basis in canon law, theology, church history or custom. The archdiocese lost. Naturally it appealed, and I became one of its targets. A significant part of its opposing brief was not a serious challenge to the content of my declaration but a detailed, invasive personal attack on my character, credentials and motivation. It got them nowhere; a special master overruled just about every objection lodged against the declaration.

From there the cardinal's appeal went to the California Supreme Court where, on July 25, 2005, it was again denied. Mahony and his lawyers appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. On April 17, 2006, the Supreme Court refused to review the lower courts, hence their rulings stood.

That battle involved the files of two priests. One would expect the cardinal and his team to get the point, but they did not. The fight continued until this January. Even then, with final defeat looking them in the eye, the cardinal's lawyers planned yet another strategy for yet another postponement and more time to spin, twist and delay. It was not to be. On Jan. 31, the judge ordered the trove of about 30,000 pages of documents released and that they had to show the names of the cardinal and his aides.

Shortly thereafter it was discovered that the archdiocese had released only around 12,000 pages and that many of those had the names of church officials blacked out, contrary to the judge's order. The public response was swift. The cardinal's lead counsel, Michael Hennigan, said he had no idea why the documents were missing, and promised more would be forth coming. More spin and roadblock right up to the wire!

The saga is not over and probably never will be. The damage extends beyond the victims, their families and the key players in the legal debacle, to the church itself. The cardinal, in his self-serving obsession to first shortchange the victims and then to protect himself and the archdiocesan administration from the exposure of their despicable actions in sacrificing the innocence of children for the clerical image, has severely damaged any possibility of healing. This nearly decade-long nightmare has plunged the hierarchy's barely existing credibility into a tailspin.

From the papacy on down, the Los Angeles abuse history is marked only by narcissistic efforts to save a terminally shattered image. There is little doubt that Pope Benedict XVI and his predecessor knew the score in the archdiocese. Unconfirmed reports say Vatican representatives were in on the settlement negotiations. After all, $660 million is not small potatoes even to the Vatican.

How much is the cardinal's hat worth and who paid the bill? In the end the dollar costs are astronomical but pale by comparison to the costs incurred by the people of God who have paid the price of this colossal betrayal with their faith.

[Thomas Doyle is a Dominican priest, canon lawyer, addictions therapist and longtime advocate for clergy sex abuse victims. He worked as a consultant to lawyers representing abuse victims suing the Los Angeles archdiocese.]