Artist Gracie Morbitzer at her studio in Columbus, Ohio, on Feb. 27 (RNS/Kathryn Post)

On an unseasonably warm autumn day in Columbus, Ohio, in 2016, Gracie Morbitzer recalls sifting through a box of free items at a cluttered yard sale. Beneath beat-up nail clippers and toilet paper rolls, she salvaged two hand-sized pieces of wood.

"Being a very broke new college student, any art supplies I could get my hands on, I would take with me," Morbitzer told Religion News Service. The Columbus College of Art and Design, where she attended, didn't have many avenues for Morbitzer to express her Catholic faith, so she decided to paint an icon of Jesus on one of the pieces to adorn the cinderblock walls of her dorm room.

"I didn't know what outfit to put him in," Morbitzer said. "So I just left him in a white T-shirt for a few days. But the longer that I sat with that the more I realized how cool that really was, just being able to see him wearing something that the people around you are wearing."

Soon, Morbitzer had transformed the second piece of wood into a modernized rendering of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. Those two pieces became the first of well over 100 modern saints Morbitzer has painted since. After graduating with a degree in interior design in 2020, she soon began creating modern saints full time in her Columbus art studio, where her walls are covered in small icons she's hand-painted.

A variety of modern saints icons hand-painted by Gracie Morbitzer adorn the walls of the artist's Columbus, Ohio, studio on Feb. 27. (RNS/Kathryn Post)

Her pivot from interior designer to fine artist is thanks in part to Instagram, where her renderings of saints with dreadlocks, tattoos, headphones and cigarettes are followed by some 11,000 people. Today, commissions of her saints are in churches and schools all over the world.

As a student who grew up attending Columbus' Catholic schools, Morbitzer was always fascinated by the saints and their stories. While some imagine the saints as passive or holier-than-thou, Morbitzer, who calls the saints the "original social justice warriors," is fascinated by their humanity and tendency to push religious boundaries.

"They were always sort of stirring things up," Morbitzer said. "And it got some of them excommunicated at first. People didn't believe them, they thought they were crazy or wanted to cast them out because they were causing too much trouble. I love that about them because they thought differently than other people in their time and place."

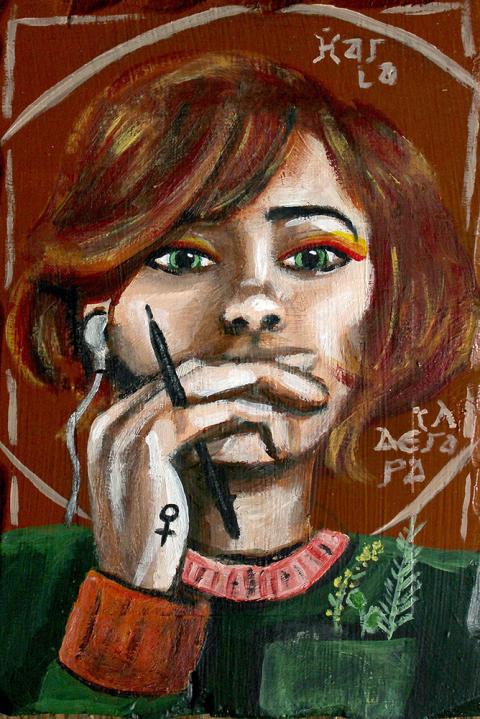

Hildegard of Bingen, for example, whom Morbitzer depicts with earbuds and flame-colored eye shadow, "was worried about pollution and deforestation and climate change in the Dark Ages," she said.

Morbitzer's painting process is methodical, even meditative. As with the first saints she painted, she begins by searching for used wood pieces, often in thrift stores. The wood is a metaphor, said Morbitzer — like the saints, the wood's defects become part of the final transformed piece. When she can, she uses an object that's connected to a saint's story, like a door section for a saint who had been a doorkeeper.

Next, she spends time researching the saint and collecting images, symbols and quotes as references. When it's time to paint, Morbitzer listens to a Spotify playlist she thinks the saint she is painting would listen to today. For Thea Bowman, who was known for teaching Black history and bringing gospel music into the Catholic Church, Morbitzer chose a playlist of modern hip-hop that sampled gospel songs.

Artist Gracie Morbitzer’s first two modern saints icon paintings at her studio in Columbus, Ohio, on Feb. 27 (RNS/Kathryn Post)

"I also recently did Thomas Aquinas, and so I picked a really hardcore study playlist. It was very ethereal," Morbitzer said.

She also gathers images of people who live where the saints once did, with the goal of authentically capturing their racial and ethnic backgrounds. She hopes that by depicting the saints as they may have looked, she can offset the whitewashed images that often dominate church spaces.

"If we have a story of someone who has been in a situation so much like ours, lived where we live, looked like we look, and still became a saint, then we can all feel less alone," she said.

Not everyone appreciates the approach, however. Morbitzer has received pushback from people upset with her saints' modern aesthetics and racial diversity.

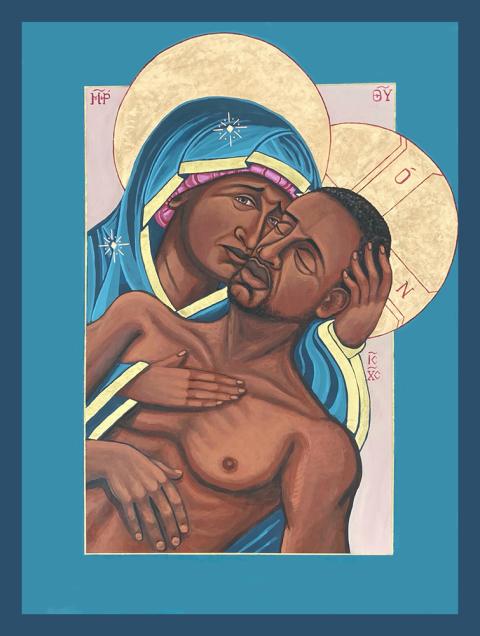

Kelly Latimore, another artist and iconographer, is no stranger to backlash. In November 2021, his icon "Mama," which depicts a dying Jesus who resembles George Floyd and is held by his mother, Mary, was stolen — twice — from the Catholic University of America. He also received a slew of death threats for the depiction.

"Our artwork over the last century has really locked Jesus into one image, which is the white, blue-eyed man," he said. Latimore added that those who oppose images of Christ and the saints as people of color are resisting the image of God in one another, something that says more about the viewer than the image. Latimore hopes the kinds of icons he and Morbitzer create will inspire people to rethink their assumptions.

"I think Gracie's work is so important because not only is she trying to have conversations about representation, but also — and this is also the hope with the work that I do — carrying the tradition of iconography and sacred art into present in a way that's potentially made new," Latimore said. "People can experience things about the saints, the life of Christ, Mary and the holy family in new ways we recognize in the here and now."

When asked why icons seem to be gaining so much traction online (Latimore has more than 26,000 Instagram followers), Latimore wondered whether it's a reaction to the "seeker sensitive" evangelical movement in the 1990s and 2000s. During that time, many evangelical churches replaced sacred art with screens and colored lights, making worship spaces appear like movie theaters or concert venues to appeal to the broader culture. When the people raised in these churches discover modern icons, Latimore suggested, perhaps they offer a fresh venue for contemplating oneself, one's neighbor and the divine.

Advertisement

Catholic author and University of California, Berkeley lecturer Kaya Oakes suggested that Morbitzer's and Latimore's icons are part of a broader pattern. She pointed to artist Kehinde Wiley — best known for his portrait of former President Barack Obama — who in 2014 created a series of stained-glass windows featuring contemporary Black subjects.

"That kind of iconography that blends contemporary with ancient or secular with sacred is really appealing to people right now," she said.

"Holy Family of the Streets," by Kelly Latimore (Courtesy of Kelly Latimore)

Of course, she added, social media provides new avenues for viewers to interact with religious art. Artists can chat directly with audiences and share about their artistic process, something unheard of during the time when religious art was produced by often-anonymous monks in monasteries.

With so much access to audiences, artists like Latimore and Morbitzer deeply consider how their work will impact viewers.

"The main question is, what is our church art for? Is it glorified wallpaper? Or could it be something that teaches us how to see not only ourselves but God and our neighbor and communities in new ways?" asked Latimore. "Can the artwork push us toward seeing the suffering among us, those who really need us?"

Hand-painted modern saints icons at artist Gracie Morbitzer's studio in Columbus, Ohio (RNS/Kathryn Post)

Morbitzer hopes her paintings might point people back to the stories of the saints themselves. Her website includes not only a quiz where users can be matched with a patron saint, but also in-depth biographies of the saints she's painted, complete with links to modern resources they might care about today — wildlife foundations for St. Francis, for example, or resources for teen parents for St. Augustine.

"The images themselves are something I hope might spark a conversation for people who have been hurt by Christianity or the ones who have done some of the hurting," Morbitzer said. "But the stories of the saints themselves are the parts I really want to share." She sends out biographies of each saint with every print she sells.

Today, Morbitzer's faith looks much different than it did when she was growing up. After spending years unpacking her faith in college and hearing stories of friends harmed by the church, she didn't know what to believe. But after diving into the legacies of the saints, Morbitzer has emerged with a new, more expansive faith. Even the saints disagreed, she said, and the church has space for each of them, flaws and all.

"I really think this knowledge I gained from saints — from their different perspectives, and how I've been able to meditate on each one and understand their diversity, that's the only thing that has been able to give me the endurance to keep trying and to change things from the inside."