In a Minneapolis courtroom in November 1984, U.S. District Judge Miles Lord had before him John La Forge and Barb Katt, a pair of pacifists who had been convicted of invading the plant of a bomb-making military contractor — the Sperry Corporation — and doing $36,000's worth of damage to a war-related computer. LaForge, 28, was a former Eagle Scout and VISTA volunteer, and Katt, 26, a graduate of Bemidji State University with a degree in philosophy, worked with the mentally disabled. Wearing suits and shined shoes and not at all scruffy-looking, coming off one barricade or another, they gave security guards little hint of their pending felonious deed.

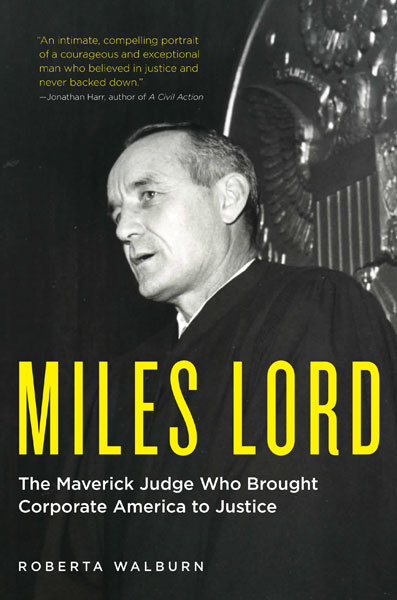

A 1968 portrait of U.S. District Judge Miles Lord (Wikimedia Commons/U.S. Federal District Court)

In his sentencing statement, Lord broke ranks with the majority of by-the-book judges who have scant tolerance for the civilly disobedient and happily ferry them off for caging in a state or federal prison. Instead, he set them free with a mild slap of six months of probation. He imposed no fine, saying with a touch of humor that "while Ms. Katt has no assets, Mr. LaForge is comparatively well endowed. He owns a 1968 Volkswagen, a guitar, a sleeping bag and $200 in cash."

To make it plain where his sympathies lay, Lord spoke of the "powerful pressure upon a judge in my position to go along with the theory that there is something sacred about a bomb and that those who do raise their voices or hands against it should be struck down as enemies of the people, no matter that in their hearts they feel and know that they are friends of the people."

Though this was far from being a landmark case in American jurisprudence, it was a revealing moment in the career of a man who almost made his way up to the Supreme Court. It likely would have happened, as Roberta Walburn explains in her engaging, fair-minded and literate biography, had Hubert Humphrey won the presidency in 1968 and possibly appointed his close Minnesotan friend Miles to the court.

Walburn has a compelling story of her own. A part-time reporter for the Minneapolis Star Tribune and cum laude graduate from the University of Minnesota Law School in 1982, she once wrote a story about Lord. He savored it and offered Walburn a clerkship, one that began in 1983 and would last nearly 18 months and give her access to her boss' professional and personal life.

Her high regard for Lord's deep commitments to social justice is firm, as when she writes that he was "courageously colorful and exuberantly outspoken, roiling the powers that be and discombobulating his buttoned-downed brethren, but leaving the man on the street cheering."

Among the powers was A.H. Robins, the Richmond, Virginia, company that marketed the Dalkon Shield, a widely used birth control intrauterine device that caused sepsis, infertility and, in 17 cases, death. With Lord as the trial judge and Walburn his courtroom clerk, some 200,000 women would share up to $3 billion as compensation for their suffering. Describing the settlement, Morton Mintz, a star investigative reporter for The Washington Post, called it "one of the most disastrous episodes of corporate misconduct in this century."

Walburn goes deep into the details of the three months of litigation.

With Robins executives attending the final court session on Feb. 29, 1984, Lord held back nothing: "Under your direction your company has in fact continued to allow women, tens of thousands of them, to wear this device, a deadly depth charge in their wombs, ready to explode at any time. … You have taken the bottom line as your guiding beacon and the low road as your route. This is corporate irresponsibility at its meanest."

In almost 20 black-robed years dealing with retrogrades like Robins, Lord never hid his judicial sentiments: "I am not anti-corporation, but I am anti-hoodlum, anti-thug, anti-bank robber and anti-wrongdoer. Some of these wolves wear corporate clothing."

Fascinating side stories flow through Walburn's lucid prose, beginning with Lord's midwife-assisted birth in an Iron Range farmhouse with no indoor plumbing. He worked as a welder to enroll in the University of Minnesota, but left to join the Air Force during World War II.

Advertisement

Returning, and after securing a law degree at the University of Minnesota in 1948, he volunteered in Humphrey's run for the Senate and Gene McCarthy's bid for the House of Representatives. Both became lifelong friends, and both persuaded President Lyndon Johnson to appoint Lord to a federal judgeship in 1966. It would last to 1985 when he left to open his own firm where four of his children signed on. He died in December 2016 at age 97.

Walburn ably covers the breadth and depth of a singular jurist. I'm pleased to say that I visited Lord after he left the bench and had time for a long conversation, one that he spiked with wit and gracious truth-telling that increased even more my admiration for him.

Bolstered by her clerking, Walburn moved ahead to practice law for 25 years "primarily representing plaintiffs in litigation against big corporations."

Wonder where she got that idea?

[Colman McCarthy teaches peace studies courses at three Washington-area universities — Georgetown, American and Maryland — and two daily classes at Bethesda-Chevy Chase High School.]