Brian Doyle, award-winning author, editor of the University of Portland's magazine, pictured in a 2012 photo. (CNS/Tim LaBarge)

Brian Doyle — poet, essayist and novelist — died too young from what he called "a big honkin' brain tumor" at age 60. He was "arguably" (as critics say) one of the best Catholic writers of his generation.

I don't like to argue. So I'll just say it: Brian Doyle is the best Catholic writer of his generation. He is also one of the best essay writers of any generation.

Ian Frazier, author of Lamentations of the Father, put it like this: "Brian Doyle wrote more powerfully about faith than anyone in his generation. … [He is] a writer whose work will last and whose reputation will grow." Among Brian's honors that have not been ballyhooed is his 2008 Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, whose company includes Saul Bellow, Kurt Vonnegut and Flannery O'Connor.

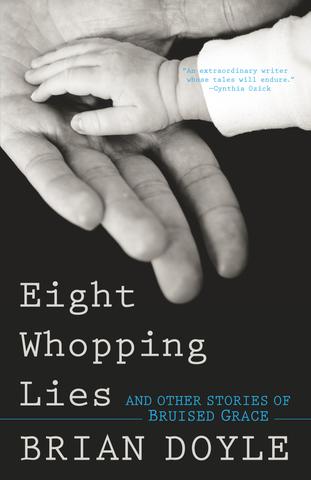

Brian's art and craft glow in his last published book Eight Whopping Lies and Other Stories of Bruised Grace. In one of the 38 essays, "A Prayer for You and Yours," he describes "two Catholic Churches, one a noun and the other a verb, one a corporation and the other a wild idea held in the hearts of millions of people who are utterly disinterested in authority and power and rules and regulations, and very interested indeed in finding ways to walk through the bruises of life with grace and humility." These are the readers of Brian's books.

In another book, A Sense of Wonder, selected essays from his baby, Portland Magazine ("the best university magazine in America," according to Newsweek), Brian writes in his intro that every time his spirit is low, "Without fail a story comes and thrums on my heart until I am bruised with joy." With self-deprecating humor, he observes that every story he chooses for Portland Magazine, and by extension every story he writes, can only be defined "with such ephemeral gossamer murk as epiphany or awakening or shiver of the heart."

In a shivering essay in Eight Whopping Lies, Brian takes a walk with a monk. "I love to cut the grass here," the monk says, "for I sometimes come to a sort of understanding with the grass, and with my legs and arms and back, a sort of silent conversation in which we all communicate easily and thoroughly. Do you have any idea of what I mean with all this?"

"I think I do," Brian says. "I have children and a fascinating graceful mysterious wife, and sometimes we are like five fingers in a hand. And sometimes when I write, that happens, that the page and my fingers and my dreams are all the same thing for an hour, I always emerge startled."

Self-portrait of Brian Doyle (Courtesy of Mary Doyle)

Brian confesses to "swimming and thrashing and singing in [words] ever since I was two and three and learning to make sounds that turned people around in the kitchen and made them laugh or occasioned sandwiches and kisses or sent me to my room, ever since I was four and five and learning to pick out letters and gather them together in gaggles and march them in parades and enjoy them spilling down pages and into my fervent dreams."

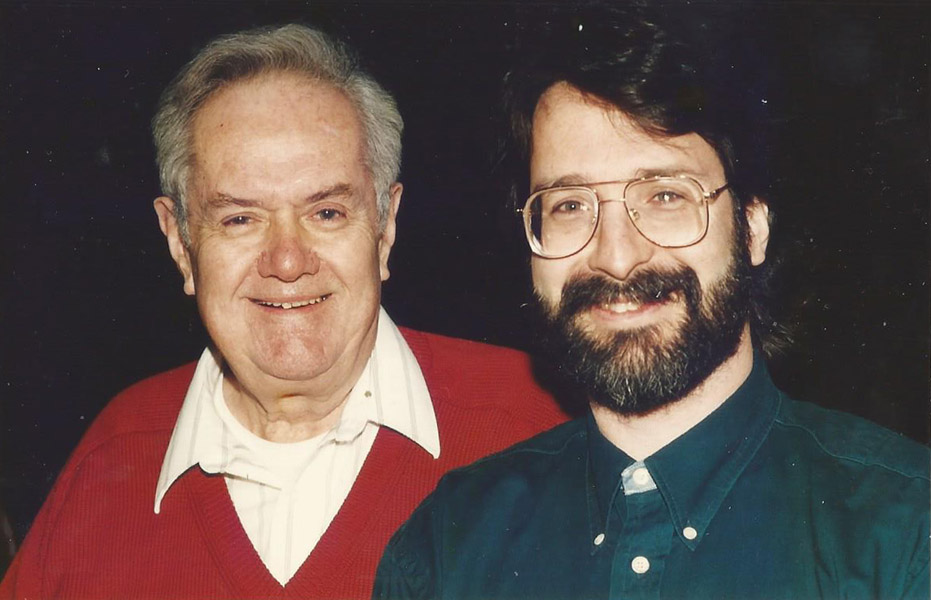

Brian found inspiration in his father, Jim, an accomplished journalist who headed the Catholic Press Association for 30 years. Brian once told an interviewer, "He taught me more than anyone or anything that stories swim by the millions and most of being a writer is listening and seeing and then madly scribbling." In another essay, Brian tells a student he became a writer "because of the staccato staggered music of my dad's old typewriter in the basement. Because when he really got it going you could listen to it like a song."

Jim Doyle wrote a loving remembrance. He notes, "Some people may have thought Brian was a wild writer, uncontrolled, not paying attention to the rules, but that was not so. He was a hard worker and steady writer. He went to his university office early every day to write his own stuff, before others showed up, as well as during the days and weekends at home. The result was hundreds of hours of beautiful writing every year."

Brian Doyle, right, with his father, Jim (Courtesy Jim Doyle)

Great teachers like E.B. White instruct writers to keep their sentences short. Brian sometimes wrote a sentence that galloped for a page. Great craftsmen like Elmore Leonard and Stephen King tell writers to eschew semicolons. Brian studied music and had a feel for beats and pauses. A period is a full pause. Sometimes a Doyle paragraph just needed to catch its breath and that's where the semicolon, a quick pause, came in. Brian used them to save the reader from falling off a chair from the sheer energy of his stories. As a book editor, I've told authors, "When you know the rules, you can break the rules." I told Brian how much I loved his stuff.

Advertisement

Brian was an original whom you can't compare to any other writer. One of his essays is sidesplitting. He shares excerpts from letters he's received. Here's one: "Our book club had to read your novel for our April meeting and my question to you is this: who were you trying to ape and copy, James Joyce or Jorge Luis Borges? Please respond to this question: I have ten dollars riding on Borges."

One thing that does distinguish Brian from other writers is joy. Like Robin Williams, he had a direct line to his subconscious mind, and phrases fell onto pages like letters from a Scrabble box, making up new and delightful combinations of words. I think Brian also worked on a divine frequency, and that is why everything he wrote smacks of joy, bruised joy. Only a tender heart can suffer a bruise, and only a bruised heart can express tenderness. Read Brian's Soul Seeing column, "The day I stood simmering in shame" as soon as you finish this piece.

Brian wrote to express joy, gratitude, humor, love, tenderness and compassion, but he worked to provide his family with a good quality of life. You have to sell a lot of essays to a lot of magazines at $200 a pop and a lot of books at 10 percent royalty just to put food on the table. That's why Brian always held a full-time job — at U.S. Catholic magazine, Boston College magazine, and the University of Portland — where he did for money what he loved: "catch and share stories."

"What could be holier and cooler than that?" he told The Oregonian. "Stories change lives; stories save lives. … They crack open hearts, they open minds."

When Brian was diagnosed with brain cancer, people from all over the country wrote to console him. He asked them to just keep laughing.

"Be tender to each other. Be more tender than you were yesterday, that's what I would like. You want to help me? Be tender and laugh."

[Michael Leach is a semi-retired editor and publisher who worked with hundreds of Catholic authors in the U.S. and abroad from 1970 to the present at The Seabury Press, the Crossroad Publishing Company and Orbis Books. He edits NCR's Soul Seeing column.]