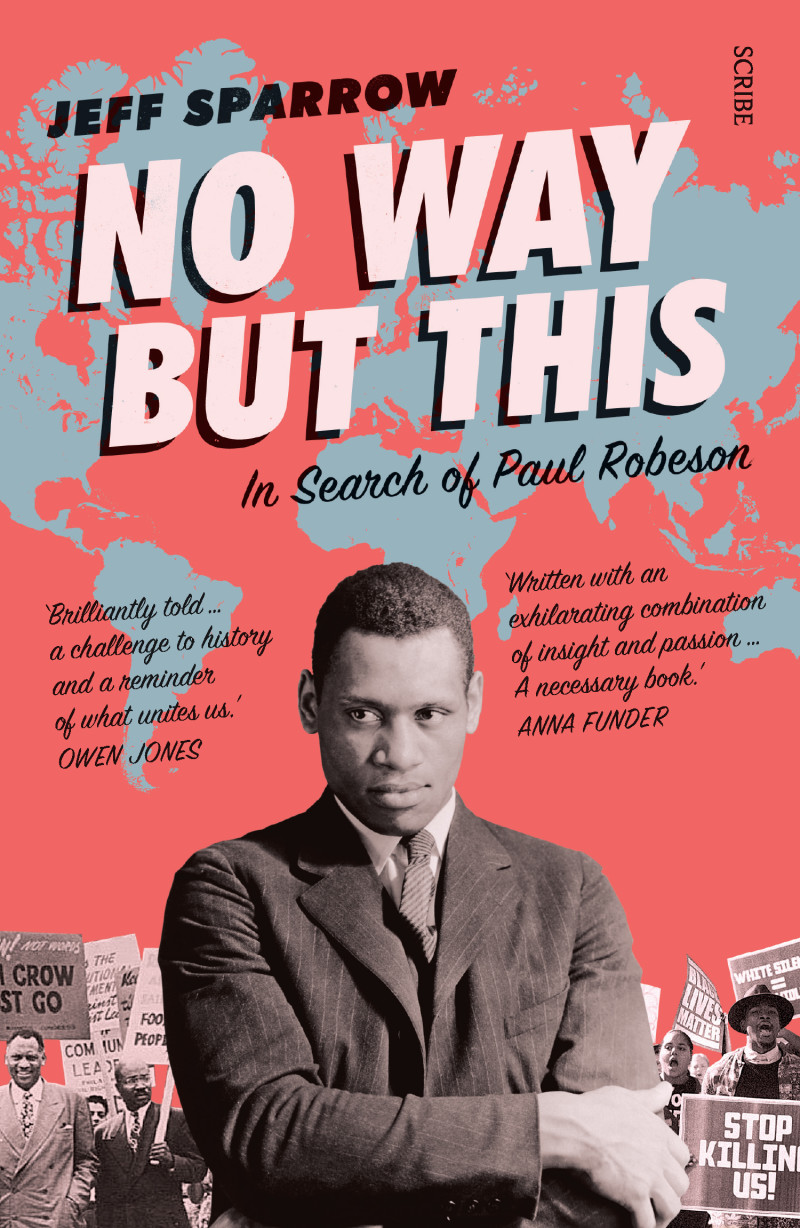

Paul Robeson in 1942 (Library of Congress/FSA/OWI Collection/Gordon Parks)

Australian journalist Jeff Sparrow's long journey into the mysteries of Paul Robeson, the now nearly forgotten African-American entertainer and controversial citizen, is not a standard biography. Rather, he has combined a series of literary forms to clarify the career of one singer, actor, activist.

First is the travelogue. Sparrow takes us to Williamston, North Carolina, where Robeson's father and other family members were slaves; Princeton, New Jersey, where he grew up; Harlem, New York, which sharpened his identity as a black man; London, where he tasted fame; Wales, where he joined the labor movement and sharpened his political identity; Barcelona, where, during the Spanish Civil War, he chose sides in the early face-off between fascism and communism; and Russia, where his commitments led to the destruction of his career.

Sparrow travels through or settles down in these scenes, checking out theaters, hotels and neighborhoods in search of people who 80 to 100 years ago saw, heard or knew this dignified, handsome, golden-voiced and courageous man. I would have told Sparrow that my baritone father, my mother at the keyboard, sang and taught us "Ol' Man River," and I saw and have replayed the 1936 film of "Show Boat," in which Paul both sang and embodied the song.

Finally, Sparrow is part novelist, part editorial writer. His central theme is Robeson's dedication to his fellow black citizens. While in college, Paul followed the example of his father, William, a Protestant minister with a classical education, focusing on Latin, German and English while singing at family entertainments.

He won a scholarship to Rutgers University, which he described as the defining event of his life because it proved to him that he was not inferior to the white people who denied him equality. Considered one of the greatest football players of his generation, he won 14 varsity letters and joined Phi Beta Kappa for representing the college's ideals. Scheduled to compete for an oratorical prize, he almost withdrew to be with his father, who was on his deathbed; William said, "I don't care what happens to me, I want you to give your speech and win." He won. And his father died.

In 1925, with his wife Essie, Paul moved to London to pursue a career in show business, playing roles in Eugene O'Neill's "The Emperor Jones," about the U.S. invasion of Haiti, and Jim Tully and Frank Mitchell Dazey's "Black Boy," based on the tragic career of boxer Jack Johnson. He sang on BBC programs and "Show Boat" in 1928. Paul and Essie stayed in London because they found that the British appreciated Paul in a way that race-conscious Americans did not. In these years, Paul chatted with George Bernard Shaw and James Joyce, living as an English gentleman.

Unfortunately, his elevated lifestyle led to an affair with another woman, so Essie wrote a book including his infidelity while she developed a friendship with Noel Coward. Paul and Essie divorced, but divorce did not bring happiness, and they returned to living with one another.

More significant, in the long run, is Paul's moral certainty that European countries gave black people more respect than did the United States. In Wales, 5,000 people attended a meeting where he spoke and sang in tribute to 33 Welshmen who died in the Spanish Civil War. He explained that he had come because the men who died had been fighting for him and black people everywhere.

Meanwhile, the fascist winner of the war shot and killed lawyers, schoolteachers and "others corrupted by modernity." By the end of World War II, Paul became convinced that the values they had fought for would educate his young son in his native America. But between June 1945 and September 1946, 56 black people were murdered in an outbreak of lynch law violations as the law was deployed to restore pre-war social order. In a face-to-face encounter with President Harry S. Truman, when Robeson asked why the president had not concentrated on lynching, an angry Truman stood up and the meeting was over.

Advertisement

The House Un-American Activities Committee accused Paul of being a communist and although he had never formally joined the party, he was convinced the communists were more devoted to justice for American Negroes than Congress was. He told the committee, "You want to shut up every Negro who has the courage to stand up and fight for the rights of people. … And that is why I am here today."

A congressman asked, "You think so highly of Russia, why don't you go live there?"

"Because my father was a slave," said Paul, "and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here and have a part in it just like you. And no fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear?"

On March 27, 1961, in Moscow, Paul Robeson was found semiconscious on his bathroom floor, bleeding from both wrists. "I am unworthy," he moaned. He had tried to kill himself. They diagnosed depressive paranoid psychosis. Essie died in 1965, and Paul died in 1976 at age 77 of a stroke while under care of his sister in Philadelphia. He was buried in Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York.

What would I write on his tombstone? Following his judgment, I would take the last line of "Ol' Man River," the version personally rewritten by Robeson and performed at a pro-Spain labor rally in England that brought down the house:

Instead of "I'm tired of livin' and feared of dying," he replaced it with, "I must keep fightin' until I'm dying." And then, like history, "He just keeps rolling along."

[Jesuit Fr. Raymond Schroth is editor emeritus at America magazine and a full-time writer living at Fordham University.]