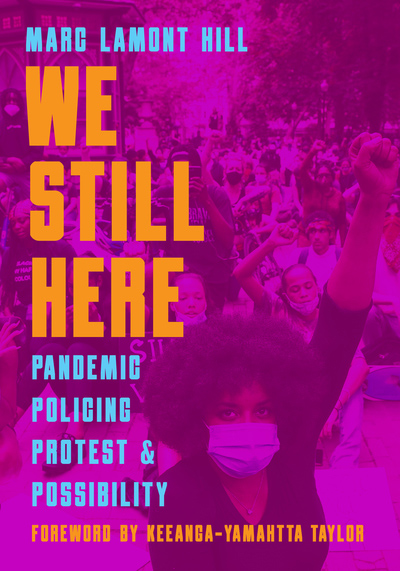

People in Rochester, New York, react Feb. 23, after a New York grand jury voted not to indict police officers in Daniel Prude's death. Prude, a Black man, died after police put a spit hood over his head during an arrest March 23, 2020. (CNS/Lindsay DeDario, Reuters)

"The thing we have to do to keep us alive could also be the thing that kills us," writes Marc Lamont Hill near the beginning of his remarkable book We Still Here: Pandemic, Policing, Protest, and Possibility, neatly summing up the conundrum of being Black in America in the face of COVID-19, police violence and white supremacy.

We Still Here aims to make clear the interconnected structures of oppression that have been clearly revealed in the past year: how policing, prisons, colonialism, including the settler colonialism of Israel and the pandemic response that prioritized economic activity over people, all point to a racialized "politics of disposability" that structures the institutions of our society to deprioritize and devalue certain lives, especially Black lives.

Hill begins his book discussing the racially disparate dangers of the COVID-19 pandemic. People of color, because of the ways a racist society has disproportionately led to their impoverishment and segregation in crowded communities, were disproportionately at risk of death from COVID-19. Hill lays out the implicit hierarchy of who got to be safe from the coronavirus along lines of economic privilege and ability as well: from the ways that "economic power enables social distance" and so the wealthy had freedom to keep safe at home in ways the poor never could, to the "politics of disposability that write off people sitting in prisons, immigration detention facilities, nursing homes, and other places of confinement." Entire confined communities were judged not worth protecting from the pandemic.

What Hill is describing in the COVID-19 response is what abolitionist geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls "organized abandonment": an organized societal response to remove resources from communities of color, replacing investment in such communities with "organized violence" against them in the forms of prisons and policing. And prisons and policing are the other existential threat to Black Americans that Hill turns to in the later parts of his book. For Hill, as for Gilmore, prisons and policing are an attempt to cover up the harm brought about by the abandonment of impoverished communities of color.

What is the Christian ethical response to such "organized abandonment and organized violence"? We might call it "organized liberation" — joining the growing movement for prison-industrial complex abolition, for a world where safety does not depend on the white-supremacist institutions of prisons and police and where everyone is cared for.

The movement for abolition is not just about prisons and police — it is about how we create community and how we recognize communities that already exist. Resisting the dynamics that Hill identifies — dynamics of disposability, of who counts as human — is part of abolition work. So is an emphasis on mutual care for one another, meeting each others' needs for the sake of the common good.

The common good is the opposite of what Hill calls "corona capitalism": the features of our economy that "made the vulnerable more likely to experience premature death" during the pandemic. As Hill recognizes, the COVID-19 crisis was exploited for profit by corporations, and the game is rigged in their favor. Governmental power is used to support corporate interests. Or to put it in terms of abolitionist thought: policing and prisons, like corona capitalism, serve the interests of the rich.

Gilmore uses the language of "crisis" to talk about moments when social structures are in flux and how we can organize and build power to make dramatic shifts. Hill identifies the intertwined events of 2020 as one such crisis. But (as Gilmore also reminds us) the transformation to a more just society doesn't happen automatically in moments of crisis. The interests of capitalism and those who benefit from profit on the backs of the poor want to use crises to reinforce themselves, what Naomi Klein calls the "shock doctrine." That is what Hill identifies happening in corona capitalism, as the crisis was exploited to push our society toward greater inequality and hierarchy.

But there are other options. Moments of crisis are moments of possibility. Rebecca Solnit in her book A Paradise Built in Hell writes about how communities, rather than turning against each other, draw together in the wake of disasters. In the face of COVID-19, alongside the capitalist and authoritarian forces pushing us toward racialized hierarchy and disposability, we also create outpourings of solidarity and mutual aid. Crises can bring us together — if we don't let forces opposed to justice get in the way.

The question in moments of crisis, and the question Hill builds to in his analysis of the current moment, is: How will we respond? Particularly as people of faith, we have to ask: How will the church respond faithfully to this crisis? Faithful response means taking the opportunity to shift conditions of power and, in the words of the Vatican II document Gaudium et Spes, live out the truth that "human institutions themselves must be accommodated by degrees to the highest of all realities, spiritual ones." Or, to put the question in the terms of an old folk song: Which side are we on?

Advertisement

Our religious commitments make it clear which side the church should be on:

The church must oppose the "politics of disposability" that deny the humanity of Black people, prisoners and other marginalized people. Respect for human dignity demands resistance against what Hill calls the "quintessentially American truth" that "the moment you are no longer exploitable, you become death-eligible." Such resistance requires that we oppose exploitative corona capitalism and also the violent systems of policing and prisons upholding it.

And perhaps Christians can also offer an alternate vision of communal safety. Hill describes the "spectacle of violence" in response to Black death: the fundamental injustice that seeking accountability for the deaths of Black people like George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery means exposing the violence of their deaths to public view over and over. Such a spectacle may be necessary to draw attention, but it is also degrading.

Ideally the church, in the Eucharist, makes visible the presence of God as a blessing for the world. The contrast to the "spectacle of violence" is clear. To live out the contrast, the church must stand in visible solidarity with those seeking liberation: an abolitionist witness.

"In what way am I going to resist death today?" Hill writes. Resisting and overcoming death is the work of Christ. The church makes that work visible in its participation in movements of resistance and liberation.

Abolition is resistance to death and proclamation of life. On one side is death: disposability, police, prisons, punishment, capitalist exploitation. On the other is organized liberation: the promise that social structures can change, that it is not too late to build a world of solidarity and mutual care, a world without the violence of policing or prisons, built on recognition of human dignity and the quest for the common good.

Hill writes: "We are dreaming together, envisioning a free and safe world where we finally turn to each rather than on each other. If we have learned anything from this moment of Covid-19, it is that we cannot survive a crisis through individual action and practice."

This moment of crisis is a moment of possibility. And it requires us Christians to ask once again: Which side are we on?