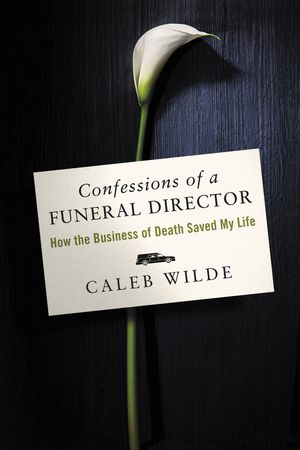

The subheading under the title of Caleb Wilde's book Confessions of a Funeral Director is "How the Business of Death Saved My Life." It could also read: "The Reluctant Mortician" or "What Not to Say."

Wilde's first book, based on his popular blog of the same name, is best when it relates details from his professional life as a sixth-generation funeral director. His behind-the-curtain sneak peeks into the world of handling dead bodies are both macabre and intriguing:

His mouth was still wide open from the day before. I took a needle and thread under the upper lip, through the left nostril, over to the right nostril, back down to the mouth and through the lower gums. I tied the two ends of the thread together and the finished product looks like every publicly viewed dead person you've ever seen.

Wilde brings us into the back room at his family's funeral home and helps us see that the techniques of handling the dead can be both artistry and healing ministry:

"Even though I have my misgivings about embalming, sometimes embalming provides grieving families a small comfort in a comfortless time. And few embalmers are better at crafting that comfort than my grandfather."

The title of the book is apt in that the details he shares are indeed confessional and compelling, in that he admits and explores his lifelong struggle both with dealing with death and with accepting his role in the family business.

For the last century or so, both sides of Wilde's family — amazingly, his mother was also raised in a funeral home — literally see dead people, all the time, and in every possible iteration.

While we may imagine that people who continually deal with death become inured to its horrors, Wilde asserts differently: "It was my duty to unzip the body bags for the two boys to see if their faces could be made presentable for a public viewing. The smell of burnt human flesh is somewhat distinct. It's not like the smell of barbecuing chicken or a pig on the spit. It sticks to your hair, to your clothing, and when I opened those bags, what I saw will forever stick in my mind."

Wilde's lifetime of spiritual grappling — he was for a time in seminary, and recently completed postgraduate work on death, religion and culture at Winchester University in England — includes not only facing death 24/7 at his family home business, but also wide reading started at a young age in multiple faith scriptures and scientific and philosophic resources, from the Bible and Torah through Freud and Nietzsche to Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

Advertisement

His honesty about this search and candor about what he perceives to be his own shortcomings are admirable. He holds his grandfather up as his icon of the perfect funeral director, both professional and warmly human:

"My grandfather stood — as is his custom — right in the middle of the family, with his arms around the shoulders of those closest to him."

Wilde most often feels he falls short in the emotional department, especially as compared with his grandfather.

"And that's our job. We are paid to be directors … to be the stable minds in the midst of unstable souls," he writes. "And honestly, I really can't handle much more. I have learned to maintain a certain level objectivity because there's only so much pain, grief, and heartache a person can share until I too start to crash and burn."

Wilde's book really comes alive — pun intended — in the stories he shares (with names changed for privacy) of actual deaths with which he has interacted.

Caleb Wilde

The chapter titled "Sara's Mosaic" is especially heart-rending. An 8-year-old girl dies after battling cancer for half of her life, and her family and friends surround her body. "Cancer has a way of creating a hodgepodge community that isn't connected by church, or sports … but by struggle, pain, and chance meetings in children's hospitals."

The family won't release her to Wilde until he has heard "their stories of Sara … [so] she could be incarnated in us so that we could love her, too, and become proxy family."

Anyone who has ever buried a child will identify with the need or hope that all who deal with the body will do so not only with reverence but with love.

Wilde's book is weakest when it tries to generalize or preach. His epilogue titled "Ten Confessions" seems a bit redundant and oversimplified.

But as a look behind the closed doors of the death industry, as well as a candid exploration of Wilde's own faith journey, this book is fascinating and compelling.

[Amy Morris-Young graduated from and taught writing at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles.]