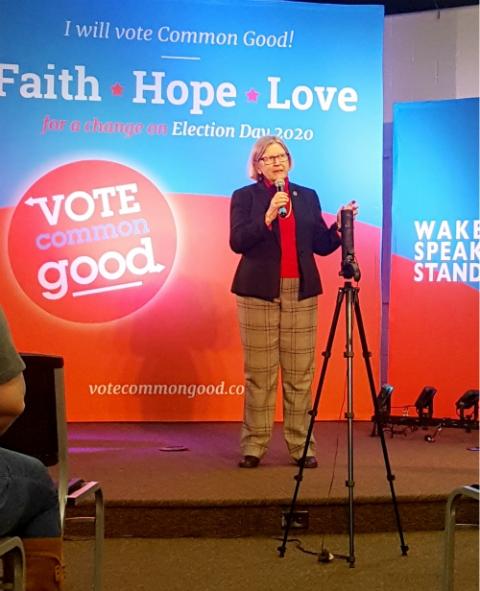

The Vote Common Good summit in Des Moines, Iowa, kicked off a 50-state bus tour, as the organization tries to bring progressive Catholics and evangelicals together to stop the reelection of Donald Trump. (NCR photo/Heidi Schlumpf)

A three-day gathering of religious progressives who are trying to tilt the political conversation toward the common good concluded with a pep talk for the long haul — both literally, as a launch to its 50-state bus tour, and figuratively, toward the months-away November election.

The call to arms came from a Catholic sister citing none other than Pope Francis.

"This is not a time for halfway measures," said Social Service Sr. Simone Campbell. "We cannot be mediocre, be boring, do it the same way we've always done it because we've always done it that way. This is not that time."

Progressives must persevere, pray and have a sense of humor, she said. Above all, "we need to do this in community" and avoid the "curse of progressives" to want to do it their own "special way."

Social Service Sr. Simone Campbell was one of a few Catholic speakers at Vote Common Good’s event on “Faith, Politics and the Common Good” Jan. 9-10 in Des Moines, Iowa. (NCR photo/Heidi Schlumpf)

"We've got to hang in there with each other, to know that the goal of faith, hope and love is bigger than any one of our particular fingerprints," said Campbell, who is executive director of Network, a Catholic social justice lobbying organization.

Her promotion of solidarity got a round of amens from the hundred or so attendees at the Feb. 9-11 Vote Common Good summit in Des Moines.

It also was an apt description of what the organization, founded in 2018 primarily by progressive evangelicals, is trying to do in 2020: build a coalition of progressive evangelicals and Catholics (and mainline Protestants as well) to prevent the reelection of Donald Trump.

By taking a page out of the religious right's playbook, Vote Common Good thinks it can make a "big dent" in Trump's base — attracting religious voters, particularly white Catholic and evangelical women who may have "buyer's remorse" about voting for Trump, said Patrick Carolan, Vote Common Good's director of Catholic outreach.

"Our goal is to reach moderate, middle-of-the-road Catholics, who in the past have voted Democratic but switched and helped elect Trump," Carolan said during a workshop on "The Catholic Vote."

Vote Common Good plans to partner with progressive Catholic organizations, such as the Franciscan Action Network, which Carolan previously headed, and through direct contact with individual voters during its national bus tour, modeled after the highly successful "Nuns on the Bus" tours organized by Network.

The goal, Carolan later told NCR, is to give moderate Catholics "permission to see that it's not a sin to vote for a Democrat."

Or as Vote Common Good Executive Director Doug Pagitt said, "We're not asking Republicans to stop being Republicans. We're just asking them to not vote for this one."

A vocal minority

The Des Moines summit included rollicking gospel music, inspiring hip-hop poetry and fiery almost-sermons from a number of activist clergy. Workshops covered topics such as racism, the death penalty, how to use social media, and how to avoid compassion fatigue.

What the event did not have, however, was an in-person appearance by a presidential candidate with a double-digit share of the primary vote. Marianne Williamson headlined a candidate forum the first night, only to leave the race the next day. That evening also included a question-and-answer panel with Republican candidate Bill Weld, the former GOP governor of Massachusetts who ran as the Libertarian vice presidential nominee in 2016 and who is trying to challenge Trump.

Left: Presidential hopeful John Delaney shares how his Catholic faith inspires his political involvement at the Vote Common Good event. Right: Marianne Williamson talks to fans and press after her appearance at the event Jan. 9. (NCR photos/Heidi Schlumpf)

There was plenty of talk about faith from former Maryland* congressman John Delaney at Friday evening's candidate forum. Delaney, who is Catholic, told the Vote Common Good summit that he and his wife try to follow the Jesuit motto of being "men and women for others."

According to a Des Moines Register poll released that day, however, the number of Iowans who said Delaney was their first choice was so small as to merit a 0% rating.

Tom Steyer and Pete Buttigieg — both of whom qualified for Tuesday's Iowa debate — sent videos of support to the common ground summit.

Despite news articles trumpeting the emergence of the religious left (and occasional shout-outs from Buttigieg), few Democratic candidates have made it a priority to court them as a voting bloc, perhaps because the numbers seem to be relatively small.

Pagitt admits his group is "working in the margins." One data analysis puts the religious left at around 5% of the population and increasing slightly, although that definition required weekly church attendance.

It's worth noting that 5% of the population translates to 10% of the electorate, and religious liberals are substantially more politically active than any other ideological group, according to that poll data analysis.

Catholics, at 25.2%, made up the largest individual religious group on the religious left, although if combined, mainline Protestants (22.3%), white evangelicals (13%) and black Protestants (9%) are larger.

Bringing together those from different denominations with a shared ideology means greater political power, as religious folks on the right correctly assumed three decades ago when they began collaborations between conservative Catholics and evangelicals that ultimately created the religious right.

Advertisement

That goal of solidarity resonated with attendees at Vote Common Good, including Catholic ones.

Katie Johnson of Richmond, Virginia, said she was inspired to collaborate not only with progressive evangelicals but also nonreligious folks who share a commitment to the common good.

"I'm interested in the intersection of faith and politics, and how people of faith can act in the public sphere out of a place of faithfulness to the Gospel," said Johnson, for whom Trump's election was a catalyst for greater political involvement.

Michael Poulin, director of justice outreach for the Sisters of Mercy in Omaha, Nebraska, also believes Catholics and evangelicals can work together, especially in the current political climate.

"It isn't just about the Trump administration," he told NCR. "There's a deeper sickness in our politics, and it's about how we bring our faith to that."

"Pope Francis has given politically progressive Catholics a place to be," he added.

But Poulin wonders how collaboration between Catholics and evangelicals will work. "What is the draw for the undecided Catholic voter — that is my question."

Challenges

For the religious right, opposition to legal abortion — and, later, to gay marriage — unified Catholics and evangelicals to work together in the public square. But the broader agenda of the religious left is more complicated.

"It's not just the March for Life, but the environmental march and immigration march and peace march. There is only so much people can do," said Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons, author of a forthcoming book called Just Faith: Reclaiming Progressive Christianity.

Patrick Carolan, who now is director of Catholic outreach for Vote Common Good, leads an immigrant rights protest in 2017 in Washington, D.C. Carolan formerly served as executive director of Franciscan Action Network. (CNS/Rhina Guidos)

But opposition to Trump has galvanized moderate and progressive religious voters, according to Jack Jenkins, a reporter for Religion News Service who has also written a book about the religious left: American Prophets: The Religious Roots of Progressive Politics and the Ongoing Fight for the Soul of the Country.

Religious progressives have led some of the most powerful and effective protest movements in the U.S., including the civil rights movement of history and today's protests for women's rights and to address climate change, Jenkins said.

"If I'm a conservative Republican strategist, that should scare me," Jenkins told NCR. "That is where the left has found its power."

But a generally accepted bifurcation of the electorate in to the religious right and the secular left hides the reality — and size — of the religious left, Graves-Fitzsimmons told NCR, who includes mainline Protestants, evangelicals and Catholics in his description of "progressive Christians."

"We need to root our own advocacy as progressives and social justice advocates in our faith traditions and realize it's been done before," Graves-Fitzsimmons told NCR. "We're not inventing something new. It's been a longstanding tradition that has been erased from our public imagination."

While Vote Common Good and other organizations are still figuring out the details of how to forge solidarity, Catholics bring an institutional history to the partnership with evangelicals, who are a few decides behind, Jenkins said.

Challenges remain, but he sees evidence of the partnership having some effect. "Whether or not that's a coalition that can hold up in the absence of Donald Trump, that's serious question," Jenkins said.

But at least one political observer is skeptical of the "religious left," because it relies on the same left-right division used — effectively, no doubt — by the religious right.

That left-right division oversimplifies Catholic social teaching, said Steven Millies, author of Good Intentions: A History of Catholic Voters' Road from Roe to Trump.

"The idea of a religious left only continues what is the fundamental problem, which is the perspective of faith becomes absorbed by the political environment, instead of the political environment absorbing the perspective of faith," he told NCR.

On a practical level, it makes sense for progressive religious folks to reach across denominational lines, and Millies doesn't doubt they could be successful in "making common cause" on issues such as immigration or health care.

"I'm just not convinced that it would be really religious," he said. "I think finally it would be a political movement of religious people, rather than religious people doing something in politics" — and the latter should be "neither left nor right."

Millies, who is coordinating a 13-week lecture series on the Catholic vote at Chicago's Catholic Theological Union, where he is associate professor of theology, wonders how welcoming the left will be of religious people.

Addressing that concern is one goal of Vote Common Good, which is providing training and coaching for candidates on how to connect with and speak authentically with religious voters. At the same time, the organization is working to change the narrative that people of faith must support Republicans.

Pagitt admits it will be difficult. "It took 40 or 50 years to build this coalition on the other side," he said. "We're not going to do it in 296 days."

But Carolan remains hopeful. "When you start talking about a Catholic-evangelical left movement, some people don't believe it's possible," he said.

Ideological division among the U.S. bishops' conference is also an impediment.

"I don't see them stepping forward and supporting this movement," he said. "But it's not going to stop us from what we're doing."

[Heidi Schlumpf is NCR national correspondent. Her email address is hschlumpf@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter @HeidiSchlumpf.]

*This story has been updated to correct that Delaney represented Maryland.