Jeremiah Chapman, prays during a 16th Street Baptist church service, Sunday, Dec. 10, 2017, in Birmingham, Ala. (AP/Brynn Anderson)

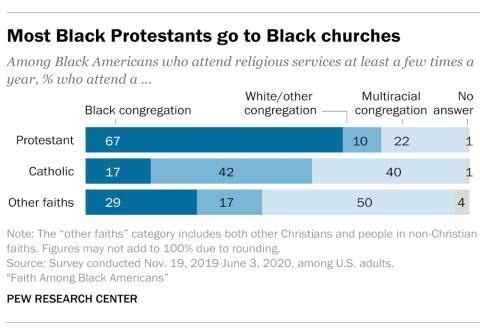

Most Black Americans attend predominantly Black congregations, but a majority think such congregations should welcome people of other races, a study from Pew Research Center shows.

"Most Black Americans, including those who go to Black churches, say that they think congregations that have historically been Black should work to diversify rather than trying to retain their traditional racial character," said Besheer Mohamed, a Pew senior researcher. "They say that if they were looking for a new church, the race of a congregation and the race of leadership would be not that important."

Pew describes its new 176-page report, based on a survey of 8,660 Black adults, as its "most comprehensive, in-depth attempt to explore religion among Black Americans."

"The number of Black respondents in this study is bigger than most entire studies," said Mohamed.

He said the breadth of the study could help dispel the notion that the Black church is monolithic and could also demonstrate that there is more to Black religious life than what happens in church.

"When we ask [about] when you're making major life decisions, they're much more likely to say they rely on prayer and personal religious reflection than to say they rely on advice from clergy and religious leaders," he added.

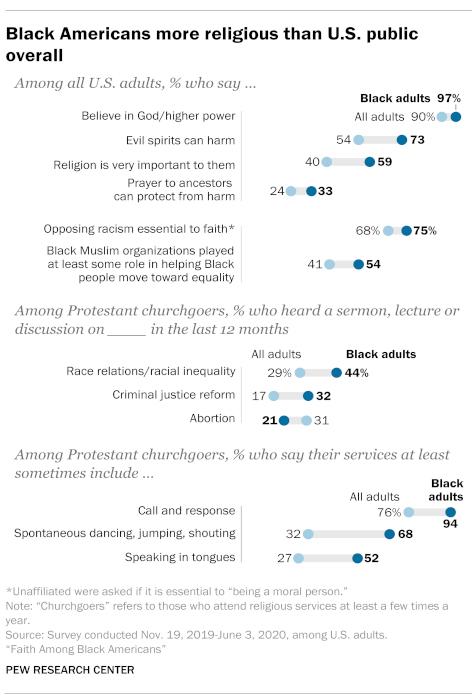

Black Christians also regard some topics as a matter of faith, even if they aren't spoken explicitly from the pulpit. "People see, for example, opposing racism as essential to their faith, whether or not they're hearing sermons about it," said Mohamed.

The large sample size allowed researchers, who conducted their survey from November 2019 through June 2020, to learn some specific differences in beliefs and practices within Black America.

For example, while 44% of Black adults overall say clergy should officiate same-sex wedding ceremonies, 37% of Black Protestants agree, compared to 62% of Black Catholics and 64% of religiously unaffiliated Black people.

The majority (67%) of Black protestants go to mostly-Black churches, compared to just 17% of Black Catholics. (Graphic by Pew Research Center)

"Despite the fact that Catholics remain a relatively small share of the Black religious profile, that difference is really striking," said Mohamed, who is also co-author of the "Faith Among Black Americans" report.

Researchers defined Black congregations as those where most or all attendees are Black and senior religious leaders are Black. Congregations labeled "white or other race" have attendees who are mostly white, Asian, Hispanic or mostly of a different (non-Black) race and are where most or all of the religious leaders are of the same different race as one another. Multiracial congregations primarily are those where no single race makes up the majority of attendees.

Black Protestants comprise two-thirds (66%) of Black Americans, while Catholics are 6% of that population. Another 3% identify with "other Christian faiths," mostly Jehovah's Witnesses, and an identical percentage (3%) affiliate with non-Christian faiths, most often Islam.

Almost one-fifth (21%) are not affiliated, mostly "nothing in particular," but 3% of the unaffiliated say they are agnostic or atheist.

The study also showed differences between Black Americans based on their place of birth and their age.

African immigrants are more likely to be religiously affiliated than U.S.-born Black Americans, but less likely to be Protestant. Both African-born and Caribbean-born Black adults are more likely to be Catholic than Black adults who were born in the United States.

Almost half of U.S.-born Black adults support the idea of religious leaders conducting same-sex ceremonies (46%), while 21% of African-born adults and 32% of Caribbean-born Black adults do.

The study found that 23% of Black Protestants are affiliated with historically Black denominations, such as the National Baptist Convention, USA, Church of God in Christ and the African Methodist Episcopal Church; 32% were ambiguous or vague about their affiliation, such as describing themselves as "just Pentecostal" or "just Baptist," while 30% were aligned with mainline or evangelical denominations that are not historically Black. Fifteen percent said they were nondenominational.

Almost all (99%) of Black Americans who attend a Black Protestant church at least a few times a year said they had heard "amen" or other so-called call-and-response expressions of approval in their services; three-quarters (76%) said there was dancing, shouting or jumping and more than half (54%) said there was praying or speaking in tongues.

Black Americans are more likely than the overall U.S. population to believe in God and say religion is important to them. They are also more likely than the general population to say taking a stand against racism is essential to their faith. (Graphic by Pew Research Center)

Those who attend white, multiracial, Catholic and other Christian churches almost uniformly were less likely to report these experiences. But more than half (54%) of Black Americans attending multiracial Protestant churches also reported that speaking and praying in tongues occurred in those settings.

Younger Black adults are less likely to attend predominantly Black congregations, with almost half (53%) of both Generation Z (born after 1996) and millennials doing so, compared to two-thirds (66%) of both baby boomers and members of the silent generation (born before 1946).

Younger Black adults were also less likely to say that they were raised in a Black church, and those who do attend religious services are less likely to attend a congregation that is predominantly Black.

African Americans are more religious than Americans overall, based on their belief in God or a higher power (97% compared to 90%); opposition to racism being essential to their faith (75% compared to 68%); believing evil spirits can harm (73% to 54%); and saying religion is very important to them (59% compared to 40%).

The study also looked at some of the tensions between what Black Americans think Black congregations should be doing and their actual actions. Mohamed said some findings show that Black Americans are more egalitarian than their congregations.

"Men and women are almost as likely to say that opposing sexism is essential to their faith — essential to what being a Christian means to them, if they're Christian — as to say that opposing racism is, but they're much less likely to hear sermons about sexism than racism. So we definitely see this difference."

Among other findings:

Church shopping: When looking for a new house of worship, Black Americans want a congregation to be welcoming (80%) and offer inspiring sermons (77%). Other factors are less likely to be considered "very important," including belonging to their denomination (30%).

Prayer: 63% of Black Americans say they pray daily; one in five (20%) pray at a home altar or shrine at least a few times a month.

Sermons: An equal number of Black Protestant churchgoers — nearly half — have heard sermons on the topic of racial inequality (47%) and on voting (47%).

Political party: Almost two-thirds of Black Democrats (64%) who go to religious services attend a Black congregation, compared to fewer than half of Black Republicans (43%). By a 2-1 margin (22% to 11%) Black Republicans are more likely than Black Democrats to attend houses of worship where most of the congregants are white.

Time: More than a quarter of Black religious service attendees (28%) say their services last about two hours, and a third (33%) say they last an hour and a half. Another 14% say their services last more than two hours.

The study had an overall margin of error of plus or minus 1.5 percentage points for the sample of 8,660 Black adults and margins of error for specifics groups, ranging from plus or minus 1.5 percentage points for U.S.-born Black respondents to plus or minus 8.6 percentage points for African-born respondents. An overall sample of 13,234 U.S. adults had a margin of error of plus or minus 1.5 percentage points.

Advertisement