Cardinal Blase Cupich speaks during Chicago's March for Life Jan. 14. Cupich told an Aug. 2 panel at an American Bar Association meeting that both capital punishment and abortion assume that "life is contingent, rooted not in the free and absolute gift of a sovereign and loving God, but in the discernment of relative worth by society." (CNS/Chicago Catholic/Karen Callaway)

Praising Pope Francis' decision to revise church teaching to forbid the use of the death penalty in all cases, Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago argued that the right to life is unconditional, universal and God-given, even for those guilty of "monstrous crimes."

"Capital punishment only continues the cycle of violence and vengeance," he said. "If there is any lesson we need to learn in this perilous age, it is that taking a human life in the name of retribution does not bring justice and it doesn't bring closure, even if it may feel that way in the moment."

Cupich's remarks were part of a panel that tried to answer the question: "Has the Death Penalty Become an Anachronism?" In what appeared to be a lucky coincidence, the Aug. 2 panel at an annual American Bar Association meeting came just hours after the Vatican announced the change in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

Other panelists noted that most countries have banned capital punishment, that the death penalty does not deter crime, and that it is applied inconsistently and arbitrarily, resulting in documented racial disparities. In some cases, the panelists said, it amounts to state-sponsored assisted suicide, while in others, innocent people have been killed.

Cupich made a moral argument, adopting the "seamless garment" philosophy of his predecessor, Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, and connecting the death penalty to the issue of abortion.

Although the moral weight of the two issues "differs greatly," since abortion involves the taking of innocent human life, Cupich said both issues force Catholics to reckon with church teachings on the dignity of the human person and the inalienable right to life.

Those teachings are often referenced in opposition to abortion but less prevalent in death penalty discussions, he said, adding: "That is, until today."

"The assertion that every human life has an inherent and inalienable value will only be strengthened if we apply this principle to the morality of defending both convicted criminals and the lives of the unborn," he said.

Advertisement

Instead, capital punishment and abortion assume that "life is contingent, rooted not in the free and absolute gift of a sovereign and loving God, but in the discernment of relative worth by society," Cupich said.

"Erasing the innate value of individual lives because of crimes committed, and removing such criminals from the human family, is an echo, I think, of the violence done to human dignity when pro-choice advocates imply that the life developing in the womb is not really human," he said.

Banning capital punishment could be a "powerful witness to the unconditional nature of the right to life" precisely because it protects the lives of "those who have been judged least worthy of its vindication," Cupich said.

Instead, a society that supports the death penalty says life is conditional, especially when secure prisons and a viable justice system can "virtually guarantee that those who have committed the most grievous acts against their fellow citizens will not pose a continuing danger to society," the cardinal said.

"Such a state, even if it does not intend to do so, inevitably weakens the ability of its citizens to defend the sacredness of human life against all the threats that imperil life in the present day," he said.

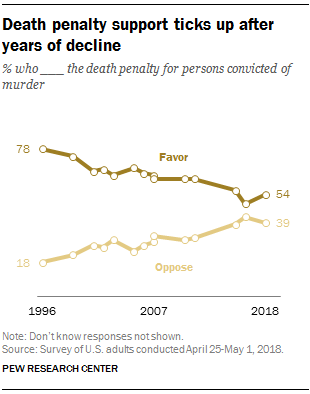

Although Americans' support for the death penalty had been declining since the 1970s, a Pew Research Center study found an uptick since 2016, with 54 percent agreeing with capital punishment for murder, and 39 percent opposed. Among Catholics, the numbers are similar: Fifty-three percent favor capital punishment, while 42 percent oppose it.

Support for capital punishment may come from "impulses deep in the human heart" that include compassion for victims and a desire to restore the order of justice, Cupich said.

"At a profound human level, we tend to believe that by executing a murderer, we are somehow helping rebalance the scales of justice," he said.

But that argument is flawed, Cupich said. "The real tragedy of murder is that there is no way to rebalance the scales of justice, no way to bring life back to those who have been killed or to restore them to their grieving families," he said.

Cupich said the pope's move to expand previous papal teaching against the death penalty comes as no surprise, since Francis has previously criticized "penal populism," which promises to solve society's problems by "punishing crime instead of pursuing social justice."

The move also illustrates the possibility of the development of doctrine, Cupich said, quoting Francis: "The word of God cannot be mothballed like some old blanket in an attempt to keep insects at bay. Rather, it is a dynamic and living reality that develops and grows."

Since the Second Vatican Council, the church has emphasized the importance of Catholics' social commitments, especially to "the sanctity of life for the least worthy among us," the cardinal said.

"We are especially to be attentive to those who live at the margins of society, the poor, the vulnerable, the weak, those whose lives are at risk, including those on death row," Cupich said. "God's plan is to bring people together and to make sure that no one is left behind."

[Heidi Schlumpf is NCR national correspondent. Her email address is hschlumpf@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter @HeidiSchlumpf.]