A 1937 report summarizing that year's meeting of a department of the National Catholic Educational Association sits on Michael James' desk at Boston College, where he directs the Institute for Administrators in Catholic Higher Education.

The headline reads, "The integrating principle of Catholic higher education," and the report focuses on educational standards and quality and on competing in the higher education marketplace without sacrificing Catholic culture's distinctiveness. Some 80 years later, that language remains timely.

"We are still talking about the same topic," said James, former vice president of the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities, which held its annual meeting in February in Washington.

Retreading the same mission-driven questions that they did a century ago is a healthy thing for Catholic schools to do, according to James. But he left the February meeting having hoped to hear more innovative approaches.

"Quite frankly, there is still a lot of room for some creativity and imagination about how we resolve or address financial challenges," he said.

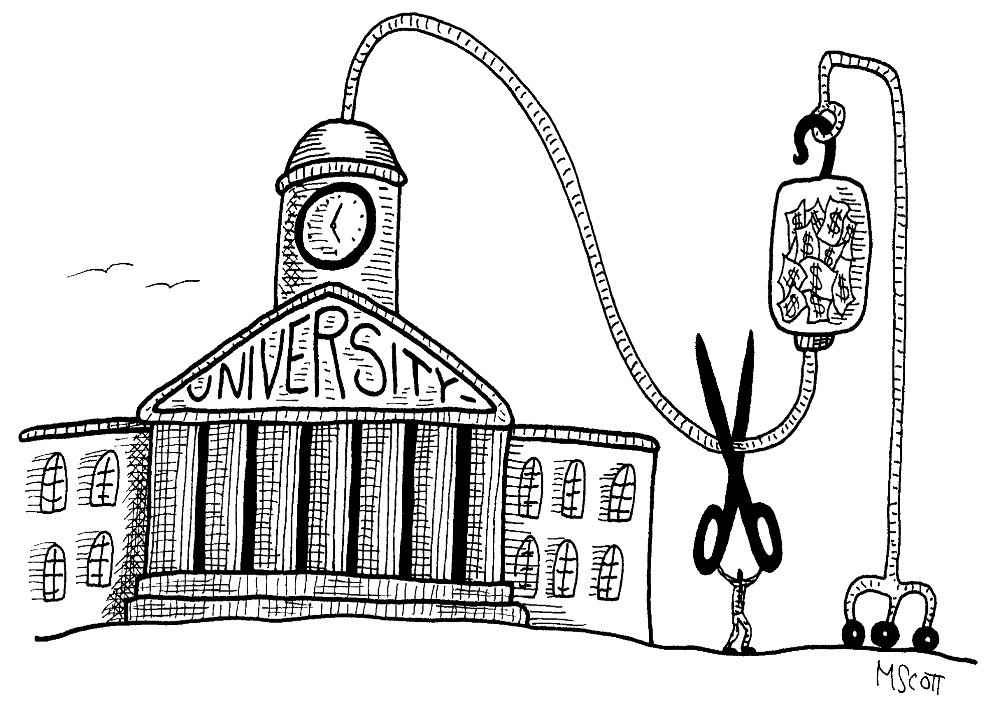

Like their secular peers, Catholic colleges and universities are exploring new financial models to compete in a difficult and fast-evolving financial space. Partnerships, mergers, consortia and a number of other approaches are on the table at many schools, as they grapple with rising tuition costs, declining endowments and dwindling public funding.

The nation's more than 260 Catholic colleges and universities collectively serve some 875,000 students. The average enrollment for a Catholic school during the 2015-16 academic year was 3,756 students, with a median enrollment of 2,581, according to the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities. From the high end of enrollments in the tens of thousands to much smaller student populations on smaller campuses, these schools have approached financial challenges in a variety of ways, and with varied success.

Some out-of-the-box thinking has generated public outcry, which suggests that some schools may be in danger of gaining the whole world while losing their own souls. Philadelphia's La Salle University recently decided to sell dozens of its most important artworks over alumni and faculty protests.

Meanwhile, Oklahoma's St. Gregory's University, which began classes in 1915, shuttered its operations after the fall 2017 semester. And a vice president at Holy Cross College in South Bend, Indiana, accidentally emailed students, "It may be that I will spend the better part of the coming school year closing down the college. … All we can do is try our hardest and hope for the best!"

"Quite frankly, there is still a lot of room for some creativity and imagination about how we resolve or address financial challenges."

-- Michael James

National statistics on how many Catholic schools are on life support are tough to come by. In a December 2017 follow-up report on a 1972 study of 491 "invisible colleges" — so christened for their obscurity — researchers found that of the 80 schools that had shuttered over that 45-year period, 41.3 percent were Roman Catholic, reports Inside Higher Ed.

Catholic schools are subject to the same questions about institutional viability as the rest of the higher education landscape, says Melanie Morey, director of the San Francisco Archdiocese's Office of Catholic Identity Assessment and Formation.

"Small institutions with limited endowments are facing tough times," say Morey, co-author of the 2006 book Catholic Higher Education: A Culture in Crisis with Jesuit Fr. John Piderit. "But for many of these institutions, that is not a new story. They are certainly under pressure, but they are nimble and with the right leadership, they may well make necessary adjustments that allow them to survive and possibly thrive."

Catholic colleges have a moral question with which to grapple: Should they really allow so many first-generation students to saddle themselves "with crushing debt in order to attend these fragile institutions?" she asks. "If so, what justifies the assumption of this burden?"

Schools cannot afford to maintain the status quo, Lucie Lapovsky warned on a panel at the February conference of the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities.

"We've always said, 'Stay in your lane. Do what you do best. Don't be everything to everyone,' " said Lapovsky, principal of an eponymous consultancy focused on higher education governance and finance. "You need to reinterpret or operate outside of your lane."

Among Lapovsky's suggestions were lowering posted tuition rates to avoid shell-shocking prospective students, diversifying tuition revenue, and creating graduate programs, which she called "the wave of the future." One school made $600,000 just by creating a summer program one year, she said.

Advertisement

The private, nonsectarian Lasell College in Newton, Massachusetts, brought a retirement community to campus. "It's a win-win," Lapovsky said. "It's a population that likes to audit the courses."

"The wedding business might not be exciting to you, but if you have a nice chapel and good food service, you can make a lot of money," she added, but she noted there are limits. Baltimore's Methodist-founded Goucher College was happy to rent space to the then-Baltimore Colts for football training, but it turned down a nudist colony, she said.

Other suggestions may draw faculty ire, including rejiggering curricula and centralizing syllabus writing. "You've got to kind of be brutal. Classics just can't make it at a certain point," Lapovsky said, "because it's a luxury good."

And when faculty or alumni think that financial woes are the faults of admissions offices shirking their responsibilities, the administration needs to remind them that "it's a new world and you have to do things differently."

James hoped to hear more discussion at the conference about collective ways that Catholic colleges and universities can collaborate, perhaps as a loosely joined kind of network, almost like a state university system.

"We might see a national Catholic university system," he said. But at the association's conference, he heard instead about what he called "creativity around the edges," rather than bigger-picture thinking.

Speakers addressed massive open online courses, new technologies and distance-learning programs that could draw more students in, partnerships with corporate entities, new certificate programs, and new marketing approaches to tuition freezes or guaranteed four-year graduation rates.

"These are not new. These are still possible options for Catholic institutions, but I didn't hear anything particularly new," James said. Some of the strategies, he added, sound a lot like ones that have been discussed since Georgetown University was founded in 1789.

"What I didn't hear, which I find significant and disappointing, are ways in which Catholic institutions are addressing opportunities to be more strategic in their collaboration," he said. As collectively mission-centric schools, in both the evangelical sense as well as addressing the social questions of the day, Catholic colleges and universities will fare better being aligned institutionally than operating as more than 260 independent institutions.

"When they leave the ACCU meeting, they go back to their individual worlds and their individual challenges and their individual strategies," James said. "I don't know how long that can sustain Catholic higher education."

There are challenges to addressing redundancy and best practices in a national strategy. "If I'm on the board of an institution, I don't want to be the man or woman who turns the keys over to someone else," James said. "That's not our current measure of leadership success." And with more than 90 percent of Catholic higher educational institutions founded within a particular religious community, and often with a unique spiritual mission, it is difficult to maintain those identities within a collective system.

Catholic schools have a history of innovating, including women's colleges, which were among the first to offer evening and weekend programs in an intentional effort to serve student needs. Many also partnered with hospitals in a way that was "absolutely mission-driven," according to James. "Mission does not inherently restrict creativity, and it absolutely can be an innovator."

At the conference, however, the sessions about financial models didn't dwell on the roles that faculty can drive mission, or on trends of ballooning administrations that are often criticized.

"You have to stay lean," Lapovsky said in response to a question from NCR. "In my case, I'm called in to talk to a board, because a board values that outside expert more than the people there." Lapovsky tells presidents they are wasting money. "They all go, 'I know, but [the board] won't listen to me,' " she said. "I feel pretty guilty. It's the truth."

Lapovsky has seen schools buck national trends by decreasing the number of vice presidents, often combining finance and administration vice presidents, creating one-stop shops of registrar, bursar and financial aid. "You have one director instead of three," she said. "I think they are more strategic. I think schools are leveling their pyramids."

"You can't control everything; you have to be willing to put your mission commitments ahead of your control."

-- Mary Hinton

At one school, where Lapovsky sits on the board, the vice president of student affairs also oversees enrollment, and the combination works well, she said.

Fellow panelist Harry Dumay, president of College of Our Lady of the Elms in Chicopee, Massachusetts, added that there's a range of institutions, and some are leaner than others. New challenges, such as maintaining data security and privacy in ways that weren't necessary a decade ago, have required bringing on larger staffs, he said.

An audience member added that schools don't do a sufficiently good job of explaining why areas like Title IX compliance and counseling services are good investments.

In a plenary session, senior education officials and school presidents discussed partnerships and collaborations within Catholic higher education.

In New England, a large number of low- to moderately-endowed small and midsize institutions presents challenges for mergers, particularly for those that are geographically isolated, according to Michael Thomas, president and chief executive officer of the New England Board of Higher Education. Many, he added, were "latecomers" to online learning.

In response to a question from NCR, Thomas said there's going to be tension when institutions rethink their financial operations.

"A lot of it primarily stems from just it's an unknown," he said. But everything can't always be kept in-house, and if a neighboring institution has a particularly strong department, it may make sense for a school to partner rather than duplicate efforts.

"Be really clear on what outcome you'd like to achieve, and then hold true to that," he advised. "It really helps in moving forward." And scaling back or turning down some opportunities is vital. "Having the confidence to say no makes it easier to be objective moving forward," he said.

Mary Hinton, president of the College of St. Benedict, said that the women's college benefited from a long-standing relationship with and geographic proximity to St. John's University, a men's college located about 6 miles away in Minnesota. The partnership allows the schools to maintain distinctive qualities while sharing a logo, branding and resources. "How you too can get to a joint brand on your PowerPoint slides" is one way that Hinton framed it.

St. John's, founded in 1857, and St. Benedict, founded in 1913, came closer together gradually over time, according to Hinton. Ultimately, the relationship was about giving up control. "You can't control everything; you have to be willing to put your mission commitments ahead of your control," she said.

Rather than having to explain the importance of working together, the school has to do the opposite: explain why the schools aren't completely merging, she said.

When schools discuss their financial futures, they would do well to remember that everyone wants "some assurance that the deepest, most valuable things that matter will be cared for and shepherded," she said.

"There has to be some language and conversation around vulnerability. It may end up being around dollars and cents. I would hope not, but it may," she added. "But I don't know that you could start that conversation there. It's just hard for people to hear when they've given decades of their lives."

James, of Boston College, continues to imagine what he admits is likely a fantasy at the moment, of Catholic schools seeing themselves as a national collective, rather than competing. "Even when we have these natural characteristics to who we are as part of the Roman Catholic Church — a global, multicultural, diverse church — in North America we're still fairly isolated," he said. "In some ways, I think that's intentional."

[Menachem Wecker is the co-author of Consider No Evil: Two Faith Traditions and the Problem of Academic Freedom in Religious Higher Education.]