The U.S. Capitol (CNS/Aaron P. Bernstein, Reuters)

Charlie and Pauline Sullivan, both close to 80 and as agile as ever, believe in getting around. They estimate that since coming to Washington from Texas in 1985 they have covered over 1,000 miles through the halls of the U.S. capitol's six congressional office buildings — three in the Senate, three in the House. As co-founders of Citizens United for the Rehabilitation of Errants (CURE National), they go to every office, in every Congress, trying to make the case that legislation for humane criminal justice reforms is both a political and moral necessity.

Working in a nation that has the world's highest inmate population — 2.3 million people in 1,827 state and federal prisons, according to the Prison Policy Initiative — the Sullivans and their advocacy efforts might appear tiny up against the massiveness of the problems ranging from the brutality of long-term solitary confinements to incessant wrongful convictions.

"To change the system," Charlie Sullivan argues, "you must in some way become part of the system. Doing this, and keeping your principles, can be a difficult challenge. But from decades of experience, it can be done. In other words, as they say in Texas, "you have to be on the jury to hang the jury."

It was an experience in Texas in 1972 — seven days in a San Antonio jail on a nonviolent civil disobedience charge — that became a spark that flamed into a blaze to take action on behalf of mistreated prisoners, ex-prisoners and their families.

It was an unlikely calling for a boy born in 1940 into the comforts of a middle-class family in Mobile, Alabama, and whose father was a dentist and mother a homemaker. Charlie enrolled in a Catholic high school, only to leave before graduating to enter St. Mary's College in Kentucky and to be ordained a priest in 1965.

"I originally saw my future," he recalled on a recent afternoon in Washington, "as a Bing Crosby kind of parish priest — coaching sports for the parochial school kids taught by the nuns, dabbling in school musicals and never offering challenging sermons."

Advertisement

But this was the 1960s, with the church roiled by the liberalizing calls of Vatican II and the country dealing with racism in the South and a mindless war in Vietnam. With no taste for being bystander amid the turmoil, Sullivan joined the civil rights and antiwar campaigns. Except for a few bishops like Raymond Hunthausen and Thomas Gumbleton, he saw little or no church leadership on these issues.

"My particular bishop was taking no stands against what I saw as social sins all around us. I was at odds with a failing church leadership and, as a matter of conscience, I resigned the priesthood in 1969." He was one of many during that time.

Within a year, he met Pauline Fox who was a former member of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet. They bonded and took to the road in a Volkswagen van that eventually carried them to San Antonio where, after Charlie's jail time, they founded CURE in 1972. It was the same year that singer Johnny Cash was in the White House to enlist Richard Nixon in the cause of restorative justice — a fruitless effort, it turned out.

During the Sullivan's Texas years, the state had some 25 prisons — all of which they visited, including Huntsville, which lead the nation in death row executions. Thirteen years later in 1985, the couple went national and brought the program to Washington with the same statement of purpose. The CURE mission:

We believe that prisons should be used only for those who absolutely must be incarcerated and that those who are incarcerated should have all the resources they need to turn their lives around. We also believe that human rights documents provide a sound basis for ensuring that criminal justice systems meet these goals. CURE is a membership organization. We work hard to provide our members with the information and tools necessary to help them understand the criminal justice system and advocate for change.

The Sullivans work out of a small rent-free office in the belfry of St. Aloysius Church blocks from the capitol. Unlike the ACLU's National Prison Project and the Innocence Project that are well-staffed by lawyers and amply funded, CURE pushes on with an annual budget of $50,000. Its strength is in its 30 chapters throughout the country

It has 15,000 members on its mailing list for a monthly, must-read newsletter.

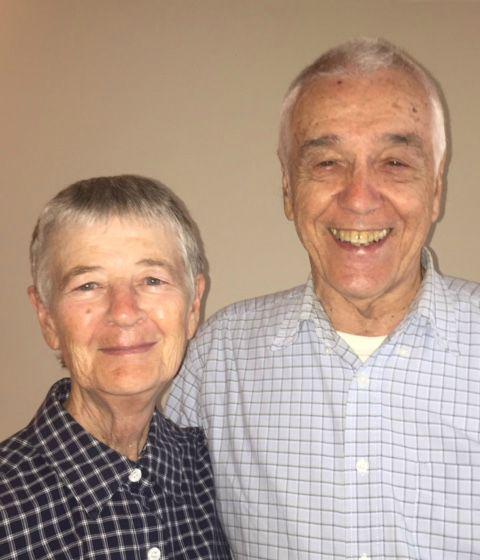

Pauline and Charlie Sullivan

In the past year, the couple has been able to persuade a few members of Congress to sponsor the Juvenile Justice Reform Act, the Second Chance Reauthorization Act, the Medicaid Coverage for Addiction Recovery and Expansion Act and others. Sponsorship hardly assures passage to a presidential bill signing, which means the Sullivan's cause-driven work goes on.

"I read and answer most of the letters from prisoners." Pauline Sullivan says. "So many of them ask for help with their legal issues and report dire conditions about their imprisonment. My greatest frustration is that I can't provide the help they request."

For Charlie, "My greatest joy over the years is working with so many wonderful people, some of whom have been with CURE from the beginning 45 years ago. Matthew 25 has been interpreted that 'I was in prison and you visited me.' But visiting is only one side of the coin. The other is advocacy, especially for the person to be released. In fact, the Catholic Worker movement interprets Matthew 25 as 'I was in prison and you liberated me.'

"The frustrations of the work include continuing year after year pushing for the release of prisoners who have rehabilitated themselves. That feeling is waived when, on occasion, the prisoner is finally waived."

The Sullivans' singular and heroic mission brings to mind the thought of George Bernard Shaw from the dedication of Man and Superman: "This is the true joy in life, the being used for a purpose recognized by yourself as a mighty one; the being thoroughly worn out before you are thrown on the scrap heap; …"

[Colman McCarthy Colman directs the Center for Teaching Peace, a Washington non-profit. He began writing for NCR in 1966, and his most recent book is Baseball Forever.]