Pastor Rodney Howard-Browne, top, prays over individuals during a service, Sunday, March 29, 2020, at The River Church in Tampa. (AP/RNS/Video screengrab)

In mid-March, Pastor Howard-Browne, head of the River at Tampa Bay Church, declared before his packed congregation: "I've got news for you: This church will never close."

A little over two weeks later, he was under arrest.

It was the first chapter in an ongoing drama playing out in Florida, where the Hillsborough County pastor was arrested on March 30 for continuing to hold worship services at his church despite local regulations prohibiting large gatherings amid the ongoing pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus.

Experts say it may be a sign of things to come. Although most faith groups have stopped meeting and shifted to virtual services, some continue to gather, and reports abound of Americans inadvertently spreading the novel coronavirus through religious events. Lawmakers, religious leaders and health experts across the U.S. are wrestling with the question: Does religious freedom mean the freedom to risk infecting your fellow believers — not to mention neighbors — with a deadly virus?

For Mat Staver, head of the conservative advocacy group Liberty Counsel, the question is at the heart of a federal lawsuit he threatened to file this week against officials in Hillsborough County. Staver argued that the county-level regulations restricting large gatherings that led to the arrest of Howard-Browne violated the church's First Amendment rights because they did not exempt churches. He also argued that authorities did not use the least restrictive means to enforce them.

The county restrictions give government the power to "wipe churches off the map," he said.

Things escalated by mid-week: Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis issued a 30-day stay-at-home order but listed religious services as "essential," with the Hillsborough County Council passing a similar resolution shortly thereafter. However, the sheriff's office told RNS that both orders are not retroactive, and while no cases of COVID-19 have been linked to the River at Tampa Bay, the charges against the pastor — which include "violation of public health emergency rules" — still stand.

The events added to tensions that have been simmering for weeks between authorities and a select few faith groups.

In the earliest stages of the pandemic, governors in states such as Washington issued stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders that barred faith communities from gathering in person, reasoning that worship will only further spread the infection. Many faith communities were eager to comply: After an Episcopal priest in Washington, D.C., tested positive for the virus in early March, religious communities across the country began to implement restrictions on their worship services before most canceled in-person gatherings altogether and began using internet tools for spiritual assemblies instead.

Where there was dissent, authorities have stepped in. In addition to charges levied against Howard-Browne, law enforcement officials in Louisiana arrested a pastor this week after he continued to worship with crowds as large as 1,000, which a local police chief described as "reckless and irresponsible" amid the pandemic. Police in New Jersey and Illinois also broke up funeral services at a synagogue and a church, respectively, when the crowds of mourners ballooned into the dozens.

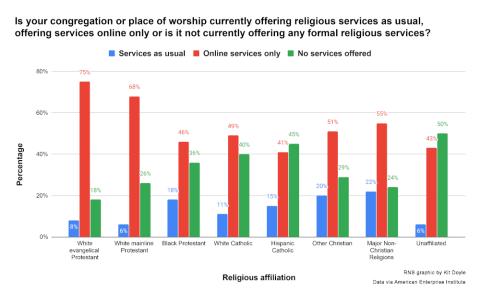

“Is your congregation or place of worship currently offering religious services as usual, offering services online only or is it not currently offering any formal religious services?” (RNS graphic)

And while the Trump administration and White House were initially slow to make any sweeping declarations concerning the responsibilities of faith groups during the pandemic, Vice President Mike Pence asked Americans on April 1 not to attend church services of more than 10 people.

"We really believe this is a time when people should avoid gatherings of more than 10 people," Pence said during an interview with "Nightline" co-anchor Byron Pitts. "And so we continue to urge churches around America to heed to that."

But even the words of the vice president, a stalwart religious Republican long championed by conservative Christians as a defender of religious liberty, are not enough to convince advocates such as Staver, who said he "absolutely opposes" the vice president's recommendation.

"You cannot have a one size fits all (approach) in a nation of 300-plus million people with hundreds of thousands of churches that perform all different kinds of functions that are essential and could not operate under that restriction," he said.

Staver argued that if hardware stores and establishments that sell alcohol are considered "essential," as many stay-at-home and shelter-in-place orders do, then so too should churches. He also insisted that churches offer essential services to communities besides worship, such as food pantries or farmer's markets, and shutting them down can have wide-ranging effects.

Not classifying worship as "essential," he said, gives "incredible power to the government that the Constitution doesn't give them in peace times or in times of crises."

Scholars such as Frederick Gedicks, law professor at Brigham Young University Law School, have argued that legal challenges to worship bans are unlikely to succeed. But Staver's list of allies is growing: Governors in Tennessee and Delaware are now either exempting faith communities from their order or listing worship services as "essential," paving the way for worship communities to continue to gather in large numbers.

The declarations have incensed many others who see such actions as dangerous. Last week, leaders of the Faith and Progressive Policy Initiative at the Center for American Progress, an influential liberal think tank, called on political leaders to abandon the practice of exempting faith communities from stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders.

"A legally imposed assembly ban that exempts religious gatherings is not based on scientific evidence," reads the group's statement. "Viruses do not discriminate, and neither should America's public health response; there is no scientific basis to distinguish between religious gatherings and nonreligious gatherings."

Their concerns were echoed by faith leaders during an online panel discussion on April 2 hosted by Duke University, where religious leaders debated the topic.

"I just think that puts a lot of vulnerable people at risk," Greg Jones, dean of the Duke Divinity School, said of the practice. "The power of these clergy is that people are going to trust them and lead them into irresponsible behavior."

Health care experts such as Michael Mina, assistant professor of epidemiology at Harvard's T.H. Chan School of Public Health, have also expressed support for curtailing worship services during the pandemic.

"Every extra person who shows up in the hospital puts everyone else at risk," Mina said in response to a question from RNS during a conference call with reporters on April 3. "I'm in support of limiting those kinds of congregation (meetings) from happening because the ramifications extend well beyond those individuals."

Those who oppose letting religious groups gather amid the pandemic point to real-world examples of the risks involved. In California's Sacramento County, a third of the region's 314 coronavirus cases have been linked to houses of worship, with 71 attributed to one church community that has continued to meet despite the pandemic. Local officials said the outbreak was connected to the region's Slavic community, which Janna Haynes, the county's public information officer, described as "close-knit."

"The unique thing with churches and with congregations is that their main expression is to gather together," said Haynes. "Unfortunately because this virus spreads through close contact with people, that is one of the most dangerous situations that they can enter into."

The county's struggles are but the latest in a growing list of religion-related outbreaks. Multiple coronavirus cases have been linked to a single March 22 event hosted by a Durham, North Carolina, church. In New York City, some have expressed concerns that Jewish Purim celebrations in early March jump-started the virus's spread in the city. Even using worship spaces for non-religious means has proven dangerous: Two people have died from the novel coronavirus and 45 people are sick following a March 10 community choir practice that took place at a Presbyterian church in Washington state.

The same is true abroad. South Korean authorities linked early spread of the coronavirus to an infected person who attended worship services conducted by the Shincheonji Church of Jesus, and gatherings at the headquarters of a prominent Muslim missionary group in India led to a "super-spreader" event that has been linked to 400 confirmed cases and at least 10 deaths in that country.

And while the vast majority of religious communities in the U.S. have stopped worshipping in person during the global COVID-19 outbreak, the number of those who continue to do so is significant.

According to a new survey conducted this past weekend by the American Enterprise Institute with informal consulting from this RNS reporter, 12% of U.S. religious groups overall continue to offer worship services as usual as opposed to utilizing online tools or canceling services altogether.

Broken down by religious tradition, major non-Christian traditions were the most likely (22%) to continue worshipping as normal despite the pandemic, followed by other Christians (20%), black Protestants (18%) and white evangelical Protestants (8%). By contrast, the communities most likely to say their community was only offering services online were white evangelicals (75%) and white mainline Protestants (68%).

Faith leaders from across the spiritual spectrum have continued to discourage religious groups from gathering in person. The Rev. Al Sharpton, president of the National Action Network, held a conference call with officials of black denominations and other faith leaders to urge clergy to discontinue gatherings for Palm Sunday and the Holy Week that leads up to Easter.

"I have been arrested over thirty times for civil rights and civil disobedience — twice for ninety days and another forty-five days for standing up for people's civil and human rights," Sharpton said in a April 1 statement in the wake of clergy in Louisiana and Florida being charged after continuing to hold services.

"These separate incidents involving leaders of faith putting people's lives in danger is not a matter of civil or human rights, nor is it a statement of faith," he said. "It is self-aggrandizing, reckless behavior of those Shepherds who would risk their sheep rather than lead their sheep."

The statement from NAN said Sharpton and the Rev. W. Franklyn Richardson, NAN board chair and chairman of the Conference of National Black Churches, planned to make a series of calls to discourage churches whose leaders had said there should be in-person gatherings on Palm Sunday and during Holy Week.

Even so, Staver dismissed examples of outbreaks erupting from religious communities. He noted that the U.S. Navy did not suspend the use of vessels when sailors on an aircraft carrier contracted the virus and said his organization is preparing legal challenges for other states where governors are not freeing up religious groups to worship in person.

"Government doesn't have the right to just wipe churches off the map with the stroke of a pen," he said.

(Adelle Banks and Yonat Shimron contributed reporting to this article.)

Advertisement