Estefanía Madrigal sits in a wheelchair propped up after her surgery, holding baby Oliver in the neonatal intensive care unit in April 2020 in Lonetree, Colorado. (Courtesy of Estefanía Madrigal)

Estefanía Madrigal, of Lonetree, Colorado, gave birth to her first son in April 2020, but it was not without complications. Thirty-four weeks into her pregnancy, Madrigal was in unbearable pain, but she did not want to go to the hospital out of fear of getting COVID-19. Finally, her husband begged her to go to the emergency room. The pain turned out to be a hernia. She had to be induced into early labor immediately and her son was born prematurely.

Madrigal had to recover from giving birth and emergency hernia surgery. Due to COVID-19 regulations in the hospital, her husband could not be in the ER with her and spent the night in the parking lot waiting for updates.

The family could not afford to stay in a recovery room in the hospital after Madrigal was discharged. The family had to wait four days to see their newborn after being discharged, and her son was not allowed to go home for 10 days. Madrigal and her husband were only allowed to visit their baby in the neonatal intensive care during visiting hours.

"If we didn't arrive by a certain time, we couldn't see him and we had to leave by 6 p.m. each day. So, he was there alone every night," she said.

It was a traumatic time for the family, but such stress was not uncommon for many new moms who gave birth during the coronavirus pandemic. Some worried their kids would not become properly socialized while others agonized over how to keep their newborns safe.

Relying on faith and family, several Latina Catholic mothers navigated the unfamiliar with whatever resources were available to them at the time, facing difficult choices that mothers before them did not have to make. Now, two years later, they are reflecting on the strange and wonderful ways their lives have changed.

Advertisement

Catholic Latina moms also faced specific challenges, including questions around sacraments, vaccines, isolation and racial disparities in health care access.

Baptizing pandemic babies

Sarai Martinez embodied being a mother, an expecting mother, a wife, a student, a sister and daughter during the pandemic. Before the pandemic, when Martinez had her first baby, April, in August 2019, the visitors room was overflowing with family, and relatives would trade visitor passes to sneak additional family members into the hospital room.

Martinez's mother-in-law moved in to help and friends stopped by with food. The family had a huge baby shower and both sides of the family packed the church for April's baptism.

Martinez had her second child, Dante, in December 2020, giving her the perspective of both pre-pandemic and pandemic pregnancy. Her second pregnancy required wearing a mask during labor, attending ultrasound appointments alone and drive-through baby showers.

Sarai Martinez and husband at drive-through baby shower at their home in Joliet, Illinois, in October 2020 (Courtesy of Sarai Martinez)

Born in Mexico, Martinez currently lives in Joliet, Illinois, and is completing a graduate degree in intercultural studies and ministry at Catholic Theological Union.

"Catholicism is very important for our family," she said. "All the sacraments are huge."

Both cradle Catholics, Martinez and her husband had their first baby baptized quickly after her birth, but for her son they had to wait six months. By the time they were able to have an in-person baptism, masks were required and the number of guests were limited.

Even trying to get her child baptized was rather complicated. She hoped to get her son baptized before he turned 1, but was unable to until 2022. She said that while the godparents she had selected for her children were baptized Catholic, they were not confirmed. The parish told her that they would need to take classes in order to be godparents, but they were not offering those classes because of the pandemic.

As Madrigal called around to different parishes in her area, she kept getting different answers about baptism and requirements for godparents.

When her son was finally able to get baptized, his godparents flew from California to attend. As soon as they landed, the godparents found out that they had been exposed to COVID-19. Madrigal and her husband couldn't pick them up from the airport and they had to wait for a negative test until they saw each other for the baptism.

Sarai Martinez and family at Dante's baptism in June 2021 (Courtesy of Sarai Martinez)

Even though her son finally got baptized, masks and all, she said it felt bittersweet, especially since they weren't able to have a big party after the baptism, as is common for Mexicans.

"None of our family came to [the baptism] other than my sister-in-law and brother-in-law," she said.

Community, family and religious education

When Maria Solis of Nebraska got pregnant with her fourth child, she was hopeful the pandemic would be over by the time she gave birth. Her husband, a third-year medical resident, got accepted into a fellowship in San Antonio the same month that Solis gave birth to their youngest child, Frankie, in June 2021.

Post-pregnancy, Solis developed mastitis, an inflammation in her breast tissue that required treatment by a doctor. She was not allowed to bring her husband or her newborn into the exam room.

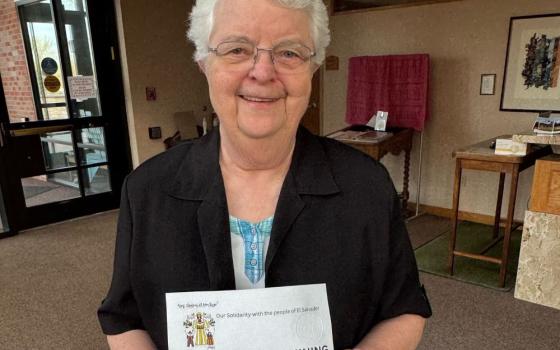

Frankie's baptism in San Antonio on Nov. 14, 2021 (Courtesy of Maria Solis)

"It removes all of your support and you just feel really isolated, especially in those medical situations," she said.

Solis said the pause on in-person Mass impacted her faith life, too.

"When I had all three of my kids, if they were born on Thursday, I was in Mass on Sunday," Solis said.

Before the pandemic, the family had been taking the young kids to Mass so they could acclimate to being in public spaces with other families, but as parishes shut down and mask mandates fluctuated, the family stopped going.

"It was really hard," Solis said.

For six months, while parishes were closed, she and her husband tried to catechize their young children from home. "We tried to keep the liturgy alive in our home," she said.

Disheartened by the U.S. church's inability to unite behind masking and vaccines — both in leadership and among fellow Catholics – that home catechesis is what kept her faith alive.

Vaccine and health care hesitations

In the fall of 2020, Araceli Palafox and her husband found out they were expecting a child. The daughter of Mexican immigrants, Palafox currently lives in Riverside, California, and works at California Forward, a nonprofit that works for economic justice in California.

"Honestly, I was so scared. It took me four or five months to share the news with everybody else," she said.

Araceli Palafox attends her first ultrasound appointment alone while her husband waits in the parking lot, in Coachella Valley, California in November 2020. (Courtesy of Araceli Palafox)

Adjusting to a pandemic world and working at a pre-pandemic speed presented its own stressors, but with no vaccine in sight, Palafox wondered about the world she was bringing a child into. "I wish that I would have given myself more grace and given myself time and space to really be in my pregnancy," she said.

Palafox was pregnant when the vaccine rollout began, and as an essential worker, she was eligible as soon as it was available. Her supervisor encouraged all the employees to get the vaccine as soon as they were able and sent Palafox a sign-up link. But after making her vaccine appointment, she could not sleep. She canceled her appointment. She was anxious and wanted to talk to her doctor first.

"The advice that I was getting, we don't know too much about the vaccine on pregnant women. But we do know that the risk of pregnant women getting COVID is much higher," Palafox said she learned from her doctor.

Araceli Palafox and husband Samuel, after testing negative for COVID-19, wait as Palafox begins induced labor in Coachella Valley, California, June 2021. (Courtesy of Araceli Palafox)

Palafox said she felt confident after talking to her doctor, but every time she went to make the vaccine appointment, she felt dread. Although eager for the vaccine to become available, she and her husband felt some hesitation because they had heard so many conflicting vaccine facts from friends and family.

"I felt like it wasn't about me. It was about my baby," she said.

Palafox was not alone. As of January, only 42% of all pregnant people had been fully vaccinated in the U.S. and only 28% of pregnant Latinas were vaccinated. Pregnant Latina women in the U.S. were also 2.4 times more likely to get COVID-19 compared to other women.

And while Hispanic Catholics are more likely to be vaccinated than white Catholics, there were conflicting messages about vaccines and masking among US Catholic leaders. For many expecting mothers, the choice to get vaccinated was not just about them, but their babies, too.

Martinez said that her midwife, who was strongly suggesting the vaccine, her doctor and her pediatrician all made sure she had access to information about the research.

Palafox waited two months until after she had her son, James, receive the vaccine. She then encouraged everyone in her family to get the vaccine as soon as they could.

Araceli Palafox holds baby James shortly after he is born in Coachella Valley, California, June 2021. (Courtesy of Araceli Palafox)

Martinez was skeptical about the history between minorities and vaccinations in the U.S. and was worried about being given false information or coerced by doctors because she was Latina. But as she saw more people in her community getting the vaccine, Martinez started to have more trust in the process. She would eventually need the vaccine to be able to return to work.

The decision about vaccines was also a family decision. Martinez's sister, who was also pregnant, served as a thought partner in discerning the vaccine and what it would mean for their birthing plans and for breastfeeding. Martinez is one of the only members of her family who is not an essential worker, so she kept that in mind as she approached them about vaccines. Latinx workers are overrepresented in the lowest-paying essential industries — a strain new mothers faced firsthand. She also wanted her dad to be on board with vaccination so her son could safely visit with his grandfather.

In the end, her family all carpooled to get their vaccines together. "I know that it is cliché with Latino families, but we are really close," she said.

In addition to vaccine hesitation, Latina moms had to figure out best practices for addressing discrimination against Latinos in health care systems. It is common for young Latinos to say they've experienced health care discrimination, "such as being prevented from accessing services; being hassled; or being made to feel inferior in some way," according to a study by Oregon State.

Martinez and her sister leaned on each other and their midwives. Both sisters had experienced racism from doctors before being pregnant and wanted to ensure that this time they had someone, their midwife, on their side. While most of the doctors Martinez met with during her pregnancy were white men, her midwife not only looked like her but was culturally competent to her hesitations.

Faith guiding the unfamiliar

Setting boundaries with a new baby is always a challenge, especially in Latino households; adding in a pandemic, quarantining and social distancing required by the pandemic made such decisions even more serious.

Mothers generally expressed feeling comfortable telling their immediate family their boundaries. But these boundaries became difficult when it came to trying to enforce pandemic protocols with in-laws or extended family who had conflicting views on the virus.

Sarai Martinez and her family at home for Thanksgiving 2021 in Joliet, Illinois (Courtesy of Sarai Martinez)

"We basically said unless you're vaccinated and take all the necessary precautions, we won't be letting you see the baby. We can FaceTime. We can Zoom. We can call. We can send pictures," Martinez said.

She felt comfortable reminding her family to take precautions like handwashing and masking, but had her husband communicate with his own family about precautions.

"I couldn't get myself to be a strict sergeant. I didn't want to be that mom, but I also wanted to make sure to protect my son," she said.

Because Madrigal's baby was born so early on in the pandemic, they did not let anyone come inside their home and only met with people outside. Madrigal said it wasn't until her son's first birthday that he began to be exposed to people.

Madrigal's parents also could not visit after she gave birth. Her family lived out of state and they worried because of their age that it would be unsafe for them to travel. For those first two months, it was just the three of them.

"All that help you hear about and people being there at the beginning, we had none of that because of the pandemic," she said.

Items dropped off by friends in April 2020 after the birth of Oliver in Lonetree, Colorado (Courtesy of Estefanía Madrigal)

Separated from support networks and family, faith grounded the new mothers.

Adjusting to motherhood during a pandemic challenged her spirituality, but being pregnant gave her strength and reminded her that life continues. "There were very dark days during the pandemic," Martinez said.

As a Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals recipient, Martinez said she has also lived most of her life in a state of deep uncertainty and has had to often lean on the vision her parents set out for her to have a better life in this country.

Martinez said she and her husband, both Mexican American, leaned on tradition, culture and their faith. They thought about how their immigrant parents were able to survive and overcome challenges during their lifetime and figured they would be doing the same.

"Take care of our baby. Take care of our family," the couple would pray.

"I felt like I always wanted to be a young mom and I was not going to let a pandemic stop my plans of having a family," Martinez said.

"I prayed every day for a healthy pregnancy and a healthy baby," she added.