A woman at Madison Memorial Hospital in Rexburg, Idaho, holds the hand of a COVID-19 patient in her isolation room Oct. 28, 2021. (CNS/Reuters/Shannon Stapleton)

Two years ago this month, as the COVID-19 virus spread uncontrollably through large swaths of the country, much of our society shut down. Church services were suspended. We all learned about "spiritual communion" and how to attend Mass via Zoom. We Catholics also learned that we have not done a very good job explaining what the church teaches about conscience.

Bishop Joseph Strickland of Tyler, Texas, speaks from the floor during the fall general assembly of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops Nov. 11, 2019, in Baltimore. (CNS/Bob Roller)

No one is better at turning church teaching into gibberish than Bishop Joseph Strickland of Tyler, Texas. He repeatedly encouraged people to not get vaccinated and that a well-formed Catholic conscience was grounds for an exemption from any vaccine mandates. Poor thing, now he is posting dumb tweets about the convoys of fake truckers protesting in Canada and the U.S.: "The freedom convoy is deeply rooted in the basic values that have built the world we take for granted," he tweeted. "We must be free to make choices for our own lives." Where is the balance? Where is the "both/and" that has always characterized the Catholic intellectual tradition?

Strickland was not alone. Archbishop Timothy Broglio of the Archdiocese for the Military Services argued that soldiers who are Catholic could refuse the vaccine. In a statement that noted the Vatican said the vaccines were morally permissible, yet some soldiers still claimed a conscientious objection to receiving the vaccine, Broglio said, "This circumstance raises the question of whether the vaccine's moral permissibility precludes an individual from forming a sincerely held religious belief that receiving the vaccine would violate his conscience. It does not."

The bishops of Colorado issued a statement that sounded like it had been written with help from the libertarian Acton Institute, or maybe from the Republican National Committee. "We always remain vigilant when any bureaucracy seeks to impose uniform and sweeping requirements on a group of people in areas of personal conscience," they wrote, without explaining how public health measures during a pandemic can be anything but "uniform and sweeping" or whether their sweeping claim about bureaucracies applies to, say, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

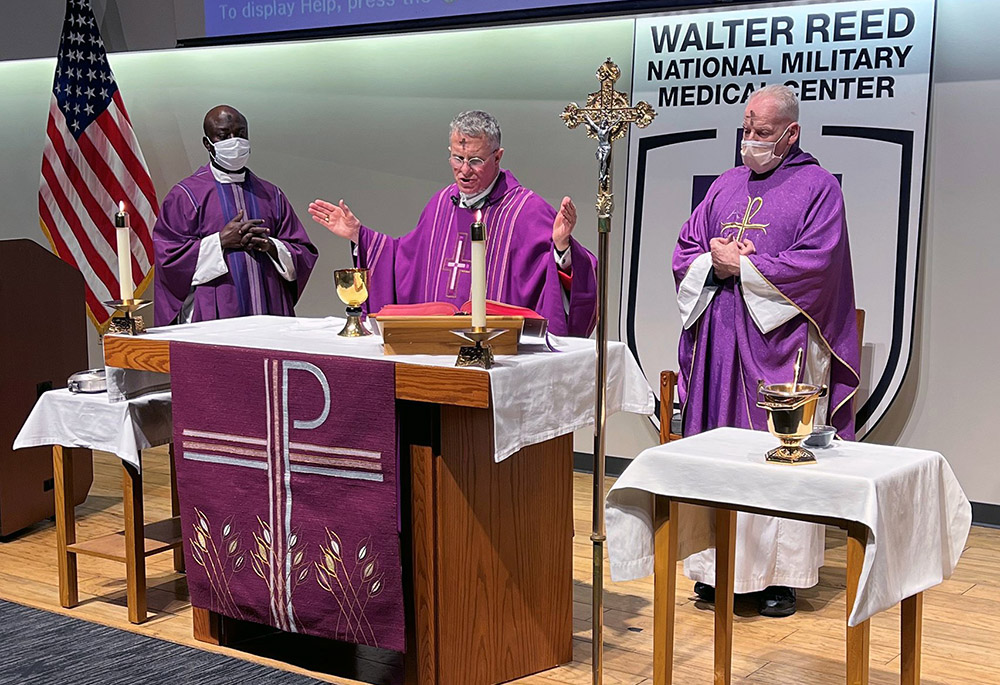

Archbishop Timothy Broglio of the U.S. Archdiocese of the Military Services celebrates Ash Wednesday Mass at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center March 2 in Bethesda, Maryland. (CNS/Courtesy of U.S. Archdiocese of the Military Services)

Let's be clear. Conscience is not the right to do whatever you want. Conscience is the opposite of self-will. Conscience is the voice of God in our hearts, helping us to apply the divine law to the moral choices we make. The caricature of conscience as a person with an angel on one shoulder and a devil on the other is just that, a caricature, but it is closer to the mark than the three statements cited above. Conscience is God's voice telling us to follow his law in a specific situation, thereby creating or strengthening the disposition to make virtuous choices.

No Catholic is more associated with the idea of conscience than St. John Henry Newman, and no comment of his about conscience is more famous than the quip with which he ended the fifth section of his famous "Letter to the Duke of Norfolk": "Certainly, if I am obliged to bring religion into after-dinner toasts, (which indeed does not seem quite the thing) I shall drink — to the Pope, if you please, — still, to Conscience first, and to the Pope afterwards." Indeed, it is black letter Catholic theology that a person is always bound to follow their conscience, even if it is in error. Just so, the obligation to form one's conscience is grave indeed.

It is an earlier passage in the famous letter of Newman's that almost seems to reach through the ages and speak to us today:

The rule and measure of duty is not utility, nor expedience, nor the happiness of the greatest number, nor State convenience, nor fitness, order, and the pulchrum. Conscience is not a long-sighted selfishness, nor a desire to be consistent with oneself; but it is a messenger from Him, who, both in nature and in grace, speaks to us behind a veil, and teaches and rules us by His representatives. Conscience is the aboriginal Vicar of Christ, a prophet in its informations, a monarch in its peremptoriness, a priest in its blessings and anathemas, and, even though the eternal priesthood throughout the Church could cease to be, in it the sacerdotal principle would remain and would have a sway.

If the great Newman had written nothing else, if he had not written the sermon "The Second Spring," nor the poem "The Dream of Gerontius," nor his "Apologia Pro Vita Sua," the phrase "Conscience is the aboriginal Vicar of Christ" would have earned him a place in the pantheon of great English writers.

Advertisement

The divine law contains many dictates, and during a pandemic, none have greater claim upon our decisions than the common good. It is the nature of a public health emergency that bad decisions by any one individual can have disastrous consequences on others, often people they do not even know. As we discovered, overburdened hospitals had to postpone important and needed surgeries for others because there was no room for non-COVID patients. As San Diego Bishop Robert McElroy told U.S. Catholic last year, "[People] do not have a right to go against the common good. That's not Catholic teaching."

It is astonishing to me that the anti-vaxxers used the exact same logic and language as the supporters of abortion rights — "My body, my choice" — yet, so far as I know, no prominent personage in either camp found in this strange commonality a reason to reconsider their position. Libertarian ideologues prate on about conscience but they are allergic to moral scruples. There is nothing liberal or Catholic about libertarianism. I repeat: There is nothing liberal or Catholic about libertarianism.

Pope Francis in 2015 waves alongside Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano, then the apostolic nuncio to the United States, right, outside St. Patrick in the City Church in Washington. (CNS/Bob Roller)

Conscience is not something lightly asserted. One wrestles with one's conscience. Conscience challenges us to act in ways that go against our interest. Conscience often exacts a high price for following it. I submit that no one in this great free country of ours should be tied to a gurney and vaccinated against their will, to be sure. The right to bodily integrity, a right that is foundational to so many legal and moral maxims, demands as much. But, the refusal to get vaccinated allows society to protect itself and demand that the unvaccinated no longer participate in, say, a church service or the military or any communal activity at which they risk spreading the virus to others.

One of the worst abuses of the idea of conscience in recent years came in 2015 when Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, the papal nuncio in Washington, introduced Pope Francis to Kim Davis, the Kentucky clerk who refused to issue same-sex marriage licenses and went to jail after she refused to let another clerk issue the licenses. The now-disgraced former nuncio told the pope that Davis was a conscientious objector. But, as I observed at the time:

If the pope wanted to show support for the right of conscientious objection, it would have been better to have him meet with a conscientious objector. Davis lost her right to consider herself a conscientious objector when she forbade other people from issuing the marriage licenses she did not wish to issue herself. Davis was not jailed for practicing her religion. She was jailed for forcing others to practice her religion. … She is a public official with a sworn duty. If she cannot carry out that duty, she should seek a work-around or an accommodation, which is what she ended up accepting, or she could have done what a real person of conscience would do: quit.

Conscience, like faith, makes demands and there is nothing that is more damaging to both than people who try and invoke it on the cheap. As we heard this week in the Gospels, people who wish to follow Jesus must take up their cross, not wave it in other people's faces.

We have learned a great deal about our society during this pandemic. The Holy Father addressed many of the challenges the pandemic highlighted in his encyclical Fratelli Tutti. The fact that the church in America has been unable to articulate a Catholic understanding of conscience in our hyper-individualistic society is one of the challenges we knew existed before the pandemic but which has been shown to be even worse than feared because of COVID-19. Especially as the bishops begin to rewrite their quadrennial document on voting, "Forming Consciences for Faithful Citizenship," it is vital that the bishops, with the assistance of theologians, search for better ways to teach what the church believes about conscience.