(Dreamstime/Víctor Manuel Mulero Ramírez)

They call it a "pandemic," meaning occurring all over the world, all around the globe. Horrible. Overwhelming. Heart-stopping.

The world has gone into lockdown, been felled — so many ravaged, so many sick, so many out of work, so much of the world looking straight into the abyss of economic collapse as a result. And all of that thanks to invisible particles from a random virus.

Except, not exactly.

In fact, another image may explain the real scope of this disaster with even greater specificity. In fact, it might even be in us that the real danger lies and not in the virus at all.

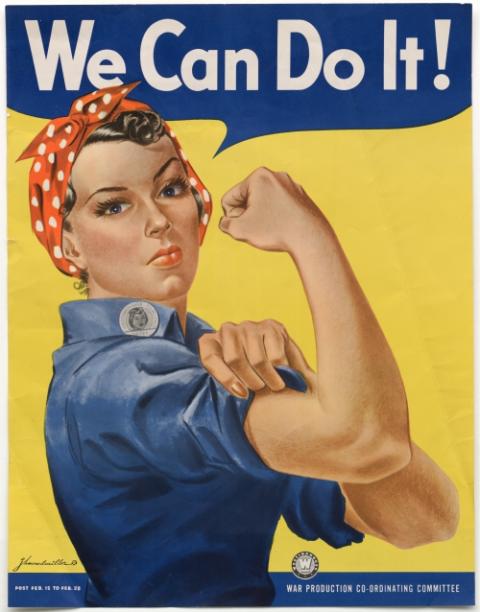

The picture that struck me hardest — and confused me most — had the aura of the World War II classic Rosie the Riveter, arms up, muscles taut, loud voice, determined look, bold answers. A real winner. The icon of a confident and effective woman, the kind of woman I myself admire, and want to see as a model for us all.

(Wikimedia Commons/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

In the '40s, Rosie left her safe, quiet kitchen and went into totally foreign territory, to assembly lines everywhere, to save the country from the plague of that time, Nazi domination of the free world.

The woman on my television screen, now, though, was somewhere between 30-40 years old. She was fired up, too, and very sure of herself. Nobody was going to tell her to do anything she didn't want to do.

"I see you're not wearing a mask, " the reporter called to her. "Is that on purpose?"

"You bet it is!" she shot back, arms flailing. "Nobody can make me wear a mask; we have rights! This is a free country. They just want to control us. But we're free! We have rights and we're not giving them up."

The irony was not lost on me: Rosie the Riveter gave up her freedom to free the rest of the world. Ms. TV Personality of 2020 — nicely dressed, full of self-confidence — claimed the freedom that Rosie won for all of us for herself, for her own satisfaction, whatever might happen to the rest of the country.

It was still relatively early in a plague that the world assumed would be over in a couple months. But the numbers of infected, the thousands of dead, the growing exhaustion in the medical community had already climbed beyond the limits of our early imaginings. Unfortunately, of course, the situation only got worse and worse as the days went by.

Yet, all the while, the United States went drifting and stumbling through the plague without any kind of central leadership or defined strategies. We were, in fact, leading the pack — a sick pack. We already had more sick and dead here than in China or all of Europe put together.

It didn't take long to see the difference between the U.S. with its growing numbers of sick and dead, and the rest of the world with their declining numbers.

The rest of the world let scientists lead them and wore masks to take care of others they might infect. Then, they got back to work, back to school, back to play. Back to their safe and quiet homes to take care of the people around them as best they could.

We, on the other hand, had a vocabulary problem. A serious one.

We couldn't tell "freedom" from "license," or "rights" from "responsibilities," or "laws" from "the common good." And while the world laughed at us (or worse, pitied us) and looked to other nations for better, more moral leadership, we stood like spoiled children and made fun of people in masks who were trying to take care of us.

The most superficial study of the Constitution of the United States is clear about our freedom, our rights, our laws and our responsibility to the common good.

First, we learn there that only some rights are unalienable — meaning cannot under any circumstances be taken away because they are part of being human, part of simply being born. Often called natural rights, they include, among other things, the right:

- To act in self-defense;

- To own private property;

- To work and enjoy the fruits of one's labor;

- To move freely within the country or to another country;

- To worship or refrain from worshipping within a freely-chosen religion;

- To be secure in one's home;

- To think freely.

The notion of unalienable rights originated in Athens, in the third century B.C. It was sealed by the Enlightenment in its 17th-century response to the fact that only the monarchy enjoyed personal freedom. It was confirmed for all people by the Constitution of the United States, however often we ourselves have failed to apply them universally.

Advertisement

Second, to be "free" means to be able to do the doable without being subject to undue or unjust constraints or enslavement. It does not mean that any of us have a license to trample on the rights of others, though we are still struggling to grasp that, too.

Third, both personal and corporate rights come with the responsibility to maintain them for the self and for others.

There is, in other words, no such thing as the freedom to pollute, or the freedom to deforest, etc. because that would create conditions that violate other people's liberty not to be exposed to pollution.

"The right of the individual to freedom and self-realization" is an honorable one, a life-giving impetus to new ideas, new ways to be alive and new ways to develop both people and property. But it does not mean that individuals can refuse to strap babies into car seats once the commonwealth has determined the need to provide special protection for babies in cars built for adults. Red lights have saved the lives of a good many of people, including the lives of those who don't want to stop at them.

Speed limits make the roads safe for all of us — and make clear at the same time that individual acts that harm others are themselves illegal.

Drugs that are dangerous or addictive are controlled by the state. To use them or sell them carries the threat of jail time for those who think that they're in a "free" country and have the "right" to do whatever they please. Common good or no common good.

"The common good" is the antidote to toxic individualism — of which we have seen a great deal in these last months. So many, in fact, that where other countries have managed to make a distinction between pathological individualism and the common good, between freedom and license, between rights and responsibilities, we are still burying our dead, closing our schools, straining our hospitals, and single-handedly destroying our economy.

It makes you wonder how the generations before us, how Rosie the Riveter and her crowd, managed to muster up the sense of responsibility to save the United States from itself.

Clearly, the land of the free and the home of the self-centered have a lot to learn from the people of all ages and all countries who manage to wear masks, avoid pool parties and understand that the fines that go with activities like those are in recognition of everybody else's rights.

There is also the ongoing echo of a Scripture in us that we've apparently forgotten and maybe ought to read again. "And then the Lord asked Cain, 'Where is your brother Abel?' He answered, 'I do not know. Am I my brother's keeper?' "

From where I stand, that question is being asked of all of us, and the answer is just as clear now as it was then.

[Joan Chittister is a Benedictine sister of Erie, Pennsylvania.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time Joan Chittister's column, From Where I Stand, is posted to NCRonline.org. Go to this page to sign up.