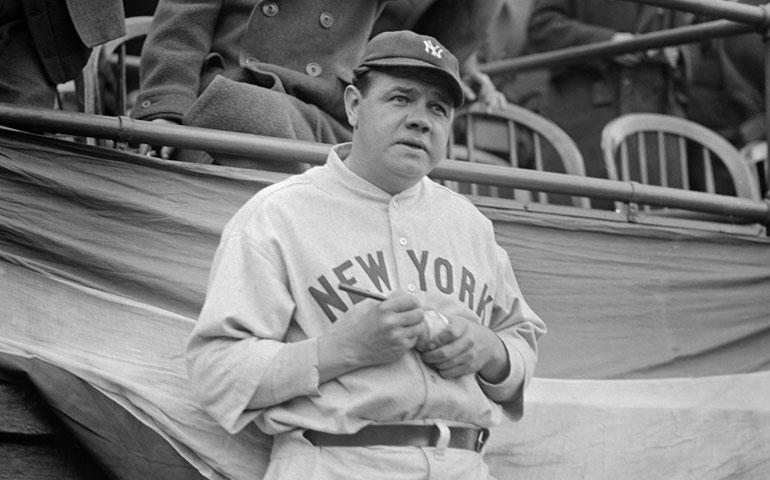

Babe Ruth autographs a baseball during the 1924 season, three years before he set the home run record of 60 as a member of the New York Yankees. (AP/Corbis/© Bettmann)

"Catholicism" might not be the first word that comes to mind when thinking of Babe Ruth. With his copious drinking and womanizing, the baseball giant didn't exactly lead the life of a religious conservative. He was, however, a member of the Knights of Columbus and invested much time and money in charitable activities, especially those involving the sick and the orphaned. This year, the 100th anniversary of Ruth entering the big leagues, we should remember all facets of this complicated man.

Many have thought that Ruth was an orphan himself. He wasn't, but he did not have it easy either. Born on Feb. 6, 1895, in a grim part of south Baltimore known as "Pigtown," Ruth -- who was of both Catholic and Lutheran Germanic background -- was rather close-mouthed on the subject of his parents. His father was the proprietor of a small, sometimes violent saloon. His mother was often ill and died young. Ruth spent his early days tramping around Baltimore, chewing tobacco, and occasionally stopping by his father's establishment to sample the booze. It seemed like the classic turn-of-the-20th-century beginning to a wayward and delinquent life.

Leigh Montville's biography, The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth, tells how Ruth, considered an incorrigible by age 7, was sent to live at St. Mary's Industrial School for Boys, run by Xaverian Brothers. Despite all of the religious instruction and the disciplined schedule, it was a tough school with many hardened kids, a number of whom went bad, and some downright rotten, such as alumnus Richard Whittemore, executed in 1927 for slaughtering a guard in prison, where he had been sent for leading a gang of thugs responsible for no less than nine murders. (The same year Whittemore was executed, Ruth, starring on a Yankee team that many consider the greatest of all time, was the focal point of a daunting lineup nicknamed "Murderers' Row.")

However, St. Mary's could also put an aimless miscreant on the right path. There, the young and unruly Ruth encountered Br. Matthias Boutlier, who would elicit his utmost respect and influence him for the better. Boutlier was a man of towering stature and enormous physical strength who could wallop a baseball for a mammoth distance.

Ruth, the future "Sultan of Swat," later said of his Herculean idol: "I think I was born as a hitter the first day I ever saw him hit a baseball." Boutlier ran the bases with a short, pigeon-toed stride and swung his bat with a sweeping, upward motion -- characteristics his little acolyte would later display as a professional.

Ruth followed the brother to such an extent that, at one point, he had spoken of becoming a priest, a vocation to which he was probably not well-suited. The athletic calling soon took hold, however. For a striving ballplayer, St. Mary's, which had its own league, was highly conducive to developing his talents. Ruth said he once played as many as 200 games in one year. Emerging as a standout, he was signed by his hometown Baltimore Orioles at age 19. Following a brief stint in the Minor Leagues, he signed with the Boston Red Sox, with whom he made his Major League debut on July 11, 1914.

In a span of months, Ruth went from living at an austere quasi-orphanage to hauling in big-league money. Montville's biography describes him in 1915 as "a kid let loose in the adult funhouse." The young athlete was newly married, and his affairs were legion. Arguably even more gluttonous was his nutritional intake: "He would eat six, eight, ten hot dogs at a time, wash them down with four, six, eight bottles of soda." To the amazement of teammates, Ruth would follow nights of corporeal indulgence by attending Mass in the morning. Truth was, amid all the debauchery, he never completely left St. Mary's, where he often resurfaced to donate money and participate in fundraising events. He especially did not forget Boutlier, for whom he eventually purchased a $5,000 Cadillac, only to replace it when the car was destroyed in a wreck.

In 1919, he joined the Pere Marquette Council 271 of the Knights of Columbus in South Boston. Soon after, he was infamously sold to the rival New York Yankees, with whom he became the greatest player of all time. Also legendary were his ongoing exploits involving alcohol, binge-eating, women and gambling, along with reckless driving and lavish spending.

It would have been easy, and perhaps appropriate, to be cynical about Ruth's Catholicism, were it not for his charity. Giving away a chunk of one's money has become an almost obligatory endeavor in recent years among prominent rich people. Such a phenomenon was not nearly as prevalent in Ruth's day. He was a star who gave to charity because he wanted to.

In 1927, the year he belted what was then a record 60 home runs, Ruth and his riches helped establish the American Legion Crippled Children's Hospital in St. Petersburg, Fla., where the Yankees held their spring training. Giving generously to others and spending recklessly on himself, he likely would have gone broke (like many star athletes these days) had he not come under the guidance of Christy Walsh, pro baseball's first agent, who ensured that Ruth would have a financially comfortable post-baseball lifestyle.

After 1932, Ruth's skills began to deteriorate, some of it due to aging, some of it due to his gluttony, which rendered him increasingly out of shape. Retiring from baseball in 1935, he coveted a managerial position but was unable to land any desirable spot. It was generally felt that Ruth was unable to manage himself, let alone a team of players.

So Ruth focused more on helping others. As World War II arrived, he teamed up with the Red Cross and made numerous trips to military hospitals. He also continued to visit countless sick children, long before it became in vogue for superstar athletes. Tellingly, sports journalist Bill Slocum said: "For every picture you see of the Babe in a hospital, he visits fifty without publicity."

In 1946, Ruth was visiting hospitals for a different reason: an inoperable cancerous tumor in his neck. A regimen of experimental treatment resulted in a dramatic recovery, but it would prove temporary. The sports icon died on Aug. 16, 1948, at the age of 53, leaving behind much of his money to the Babe Ruth Foundation, which focused on helping indigent children. A funeral Mass was held at St. Patrick's Cathedral on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, N.Y., where about 75,000 gathered outside: a fittingly massive crowd for one who truly was -- in his appetites, achievements and charity -- a giant.

[Ray Cavanaugh is a Massachusetts native who enjoys long walks, short novels and colorful characters. He has written for such publications as Celtic Life, History Today and New Oxford Review.]