Candice Marie Benbow (Courtesy of Candice Marie Benbow/Cuemadi White)

Black women are one of the most religious groups in America, according to a 2012 Kaiser Family Foundation-Washington Post survey. It's a statistic that writer, theologian and author Candice Marie Benbow often cites when discussing her frustrations with the ways Black women have been historically and currently misrepresented, or altogether erased, from Christian institutions and spaces.

After a white theology classmate asked Benbow if she was a "theologian or a Black theologian," she responded: "I'm a red lipstick theologian," eventually going on a journey to unpack her own unique and fresh perspective on Christian doctrine and faith. Benbow's scholarship, which has been cited by Black Christian women, including Catholics, for years, touches on feminism, faith, culture and Black liberation.

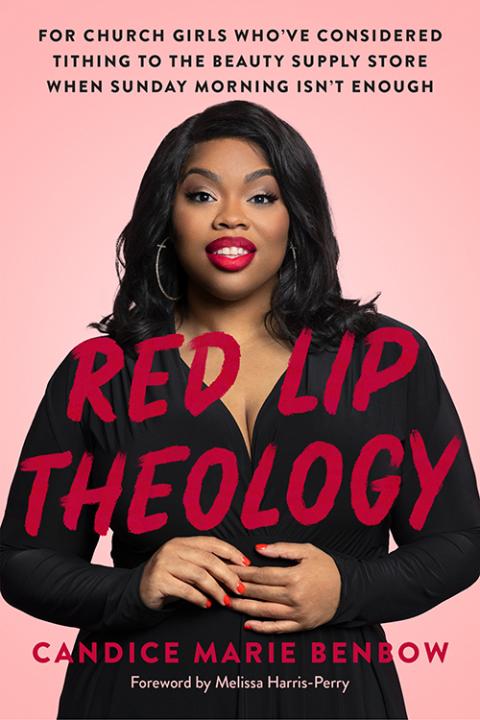

In her debut book, Red Lip Theology: For Church Girls Who've Considered Tithing to the Beauty Supply Store When Sunday Morning Isn't Enough, Benbow describes, in the vulnerable and vibrant candor she has become known for, her relationship with the church, Black womanhood, the policing of Black women's bodies and how centering Black women has strengthened her relationship with God.

For National Catholic Reporter, I speak with Benbow about her book, how the church can be safer for Black women and more.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

NCR: For the readers, explain what Red Lipstick Theology is.

Benbow: Red Lipstick Theology is the means through which and the vehicle through which I understand myself as a Black, millennial woman of faith. As somebody who was as steeped in Black church culture as I was steeped in hip-hop, it created this space where I pushed back on a lot of the things that I was taught because it was rooted in a certain kind of acceptance of inferiority that I just didn't believe was inherent to women and girls.

And so Red Lipstick Theology became the way that I was able to understand and articulate my relationship with God, God's relationship with us and our relationship with the world.

Book cover to 'Red Lip Theology' by Candice Marie Benbow

When did your journey with unlearning the toxic ideas about Black womanhood influenced by the church begin and what are things (if any) you still wrestle with?

I would say I started in college. I think the beauty of college is that you get to ask questions, and you get to explore and it's the right space to do that. I took a course and came home one day for a holiday and declared to my mom: the Black church is sexist and it doesn't care about Black women. And I went to Tennessee State in Nashville, and my mama told me the Black church can be whatever you need it to be in Tennessee, but when you're home, your butt needs to be in church on Sunday. College became a place that I was like: How can I explore what I think are also really important questions about faith, while also trying to remain faithful?

As far as unlearning, there are still days and moments when things don't work. Or don't make sense or something. I fight against the belief that somehow it's indicative of my worth or that I gotta pray more. Because so often we hear that. … And so there are moments where even I have to tell myself like: "As you are, you are good. This is not an indication of God's love for you. This is not an indication of your worth."

How do you think the church at large — and the Black church specifically — fails Black women?

Black women are not at the helm of religious dialogue. They're not at the helm of Christian faith dialogue. We're still having to fight to get seen by publishers to write. We're still having a fight for ordination and opportunities to lead in the church. I think as a church writ large, there has been this intentional erasure of Black women's voices and Black women's work, even as Black women continue to ground and be the sustaining voice of Christianity in America.

The Black church has specifically always rendered us as a servant, and has not given a very real and specific look at the theology and the teachings that ground the Black church that also lead Black women. I was listening to a sermon the other day about the birth of Jesus and the title of the message was "being pregnant with purpose." It was talking about Mary and it said: the way that you know that you're pregnant with purpose is as long as you got Jesus inside of you. Not only is that just a very crass way to talk about Mary's pregnancy and the birth of Jesus, but what does that mean for women who struggle with infertility issues? What does that mean for women who don't desire to be pregnant? What does that mean for trans men who are pregnant?

Do you think the church as an institution is irredeemable?

No, because I don't think anything or any of us is beyond redemption.

I will say the church is unrepentant because the church is unrepentant, the church refuses to be redeemed. A good friend of mine just posted today that his denomination has punted, again, his candidacy for ordination until the next round because there's not a clear stance on homosexuality. When I look at something like that, that is unrepentant. Instead of being like Jesus and welcoming everyone and realizing that there's a space for everyone, we are going to be gatekeepers that do more harm than good.

(Unsplash/Terricks Noah)

Do you think Black women should begin to build a community outside of the church?

Absolutely. … Right after my mom passed, I couldn't be there. Part of it was grief because up until that point, all of my memories about church were rooted in my relationship with my mother. I could not conceive of beginning to form new memories without her. … On another level, it was the fact that I was listening to dumb*ss sermons that really could not sustain me in the worst possible moment of my life. And I was like, I need something more than this. … I went to a Buddhist community. … every week. I began to read and, I still do read, spiritual autobiographies. … I began to honor what I knew about me that I was always afraid to articulate. And that was that I did not believe that it was just Christianity that grounded me and grounded my spiritual identity. And I began to talk more to the ancestors and engaging in much more intentional ancestral veneration.

If you are a Black woman living in America, you have to have a robust spiritual life and faith life. And I don't think that spiritual life and faith life can be sustained solely in the church that is not committed to your freedom and your liberation.

Advertisement

Who are the unconventional people who inform your faith?

Beyonce's "Lemonade" really shifted something for me. Jhené Aiko's music — I listen to her every day. I put her in the same place I put Jazmine Sullivan. I feel like they're Black girl psalmists. They articulate Black girls' experiences of my generation. I listen to H.E.R. and Brandy.

Sometimes I listen to a run in Brandy's voice because I want to hear God. … A lot of times we don't think of musicians as theologians — I do.

You've gotten into a bit of controversy online because you wrote an article about how you don't think premarital sex is a sin. Can you speak about your thinking there and the impact of the responses?

We don't know what to do in a world where Black women are free and where women live into their autonomy. I am somebody who honors my body as mine. … Creation was both an act of love and an act of trust. God created me because God loved me and because God trusts that with my body, with my mind, I'm going to make the best decisions for myself. And free will gives me the ability to do whatever I want to do. God gave me that and so here we are.

As someone who has studied the Scriptures, in the ways that I have, it is impossible to get an idea that suggests that there is only one way to understand sex. … I spent a lot of time feeling guilty or trying to shame myself for having sex before marriage. And the more I began to ask questions about "soul ties," and the more I began to study for myself, I'm like, no, the sin isn't me having sex with somebody before I'm married. The sin is me using my body out of an act of desperation that does not affirm my highest good. … Touch is holy. Intimacy is holy. … It matters to honor your body.

It matters to honor the commitment to healthiness and wholeness by allowing yourself to experience pleasure like it is OK. I want more Black women to give themselves permission to name that and to honor that for themselves.

What would you like Christian Black women who are on their journey from healing from emotional and/or physical abuse from the church to take away from this book?

I want them to know it's OK to ask questions. That God is big enough for their questions. That God is big enough for their frustrations. That it is not a sin to ask God why. It is not a sin to say that you're disappointed. It is not a sin to say that you're frustrated or that you're hurt. I want them to know that they can ask the question and that the beautiful part is the journey to the answers. That asking the hard question about faith, asking the question that you're scared to say out loud … will lead to a journey of self-discovery and a journey of discovering who God is and who you are that is worth everything.

I'm not somebody that believes that all things work together. I know that people love to quote that Scripture: "All things work together for the good of those who love the Lord and are called according to their purpose, His purpose." As a survivor, I can't say that. As a survivor, I cannot say that being raped worked together for my good. I experienced an evil because evil is in this world. … And I'm OK with that. It is an evil experience. The way that I recognize free will, that was the choice of a person and it grieved God's heart just as much as it grieved my heart.

I can also say that there are opportunities that are primed with such possibility and potential for us to discover who we are, and discover who God is in deeper and richer ways. The healing journey that I took — not the act, not the experience — [was] realizing that it was my right to be whole beyond that moment, it was my right to be able to engage in physical intimacy beyond that moment and not be afraid. And so because it was my right, it was my responsibility to do whatever I need to do to get there.

And in that responsibility, and in that journey, I discovered a lot about myself, and I discovered a lot about God, and I got to be frustrated and be like: "If you can do all things, and I believe you can do all the things, why didn't you stop that?" And God is big enough for us to ask. … I want women who are healing from trauma to know that if you ask a question, it doesn't mean you lack faith. It doesn't mean that you are wrong. It doesn't mean you don't love God. It means that you're human.

And in your humanity, you experience the brokenness of humanity. It actually emphasizes to me how powerful you actually know God to be because you know that you serve a God who could have changed it right. It's not your weakness that's caused you to ask the question but it is your capacity to really recognize how good and great God is. I want them to know that life can still be good on this side of healing and wholeness.