Author Danté Stewart in his office (RNS/CrownedGold Photography/Taja Ambrose)

When people reel off the names of American Black writers such as Kiese Laymon and Jesmyn Ward and Deesha Philyaw, Danté Stewart hopes they'll include his name, too.

"I wanted to be in the tradition of Black writing, but also wanted to do it as a Christian," Stewart said.

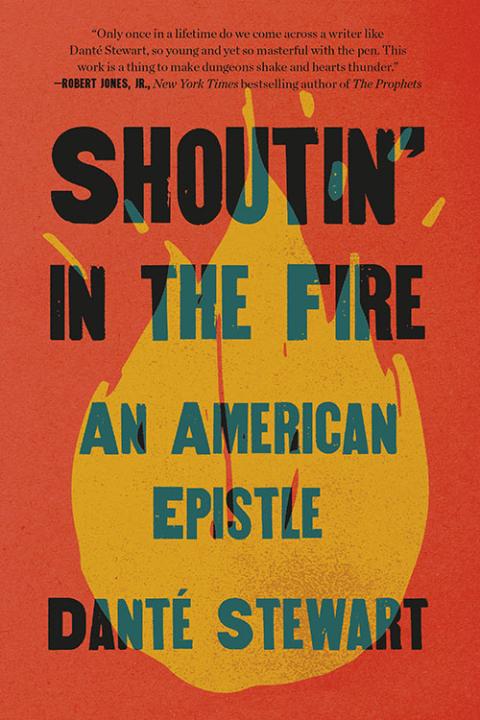

His first book, Shoutin' in the Fire: An American Epistle, released this week, isn't necessarily a Christian book, he said, though it's published by Convergent Books, which publishes major Christian writers such as Jen Hatmaker and Philip Yancey.

Instead, the author weaves together memoir and social and cultural criticism along with theology — stories about his family with stories from the Bible and Black literature. He shares his own experiences as a Black man leaving and returning to the Black church alongside the stories of Black men whose lives were cut short by police violence.

"I'm going to literature, I'm going to art, I'm going to our bodies to see what type of revelation can be had in both of those," he said.

Stewart spoke with Religion News Service about Shoutin' in the Fire, his experiences in white evangelicalism and how reading has shaped his faith and writing.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

RNS: Why did you write this book, and what do you hope readers will take away from it?

Stewart: I wrote the book first and foremost for me, because it was the type of book I needed to write and I knew I could write, but I had to challenge myself to write. But also I wrote the book for Black people. I wanted to write a book that would be incredibly hard to put in the "antiracist" category insofar as I didn't want this book to be received as something that can teach white people about Black life in hopes that white people can get better.

A lot of people ask me, "What can white people learn from your book?" I'm not really concerned about answering what white people can learn, because I'm not really concerned about what white people learn.

White people have had centuries to learn, and my book, as small or as huge as it is, can only do so much to reorganize the systems and the powers and the structures of society — you know, things like that that would actually, fundamentally change the type of experience that we're living in.

But I wanted to write something that was for us, that felt like us, that was familiar and familial in the sense that it used the language that we use, the smells that we smell, the tastes that we taste, the places that we went.

You were raised in the Black Pentecostal tradition but left for a time to attend, and preach in, white evangelical churches. What was it that attracted you to these churches and to affirmation from white Christians and church leaders?

I played football at Clemson [University]. Those who have the closest proximity to athletes are not from Black, Latino, Asian American traditions of Christianity ... [but] conservative, white and evangelical. Those things that are in closest proximity to us oftentimes are those things that we tend to ascribe the highest value.

Advertisement

Some of us assimilate just because that's the space we're in. Some of us have always existed in that space — all we know is being in spaces dominated by whiteness, and it has become our norm. So much of my assimilation was not because that was just the space that I was in, but it was because that's the space I believed that would make me feel like I mattered.

White acceptance, white rewards, white protection — so many of these things sit at the heart of what happens with many young Black people going to white college campuses. Either to escape or to survive or to thrive, we feel that the closer we are to whiteness and to white people, the closer we are to Jesus. The closer we are to them, the closer we are to success. The closer we are to them, the closer we are to protection.

What brought you back to the Black church?

A lot of it was through the murders of Alton Sterling, Philando Castile and the way the white evangelical church that I was in responded to those moments and to many of us Black people who were in that space.

My wife helped me because she challenged me to help me see myself for who I really was and the ways in which I was hurtful and harmful and the ways in which I devalued and distanced myself from Black people. My wife is a part of that, but also so much of what I was reading, whether it was through Black theology, womanist theology, Black feminist practice, Black studies and things like that.

Danté Stewart works in his office. (RNS/CrownedGold Photography/Taja Ambrose)

When I went through my change and I needed to leave the white church, I knew I had to give myself fully to the study of Black life and Black literature in particular.

In addition to sharing your own stories, you write about books by Audre Lorde, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison and James Cone alongside the biblical books of Nehemiah and Daniel. How have Scripture and Black literature shaped your faith?

My work right now at [the Candler School of Theology at Emory University] is centered around Black texts, theory and theology. I'm writing my thesis on James Baldwin, and my central question is, "What can we gain by doing a close theological reading of Baldwin's literature? What can we learn about faith, embodiment, performance, gender, sexuality, politics, theology?"

I want to do the work of a theologian that takes seriously reading Black texts as sacred texts and Black life as sacred history. In the Bible, these books — this anthology, this collection of books — have people's names, and we receive those names as divine revelation to teach us something about life, to teach us something about God, to teach us something about the world we live in, to teach us something about the stories that give us meaning: Nehemiah, Isaiah, Daniel, Hosea.

I want to receive Black names: the book of Baldwin, the book of Toni, the book of Alice Walker, the book of Gayl Jones, the book of Toni Cade Bambara and Rita Dove and Nikki Giovanni and Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. What does it mean to read these people's writing as something sacred, that can teach us about how to be Black in this world and how to love God and our neighbor to the best of our being?

And so doing the theological work means that I have to take seriously and read critically, as I do with the Bible, these stories, in the same way that I read critically the story of Nehemiah, the story of Isaiah.

I want to expand the canon, in a sense. I believe that God wants us to as well. Reading Black literature, looking at Black life honestly, expanded my theological imagination but also my ability to write a narrative that introduced and opened up and embraced and explored the Black world, which I believe God has something to say about.