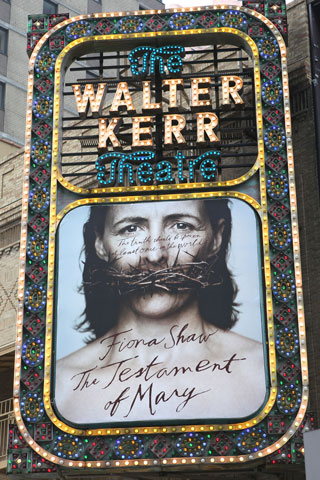

The marquee for “The Testament Of Mary” in New York City (Newscom/INFphoto.com/Walter McBride)

For centuries, she has appeared on medals, in paintings, been sculpted into statues, sung about and worshiped in prayer, making her the most iconic woman of all time. Now, in what must be her most unlikely appearance yet, Mary, traditionally considered to be the mother of God has become the star of a Broadway show.

“I was trying to bring the audience with me and see where it would go,” said Irish novelist Colm Tóibín, creator of this latest vision of Mary. “It’s not mockery. I’m serious. What I was trying to do was capture someone real.”

This real Mary of Broadway, in the world-premiere stage adaptation of Tóibín’s 2012 novella, The Testament of Mary, does not believe her offspring was the son of God or that he performed miracles. She calls his followers misfits -- “fools, twitchers, malcontents, stammerers” -- and she was not at the foot of the cross at his death, having fled for her life after watching at a distance. Decades after the crucifixion, living in Ephesus under the guardianship of the disciples, she wants her side of the story to be heard, and she tells it for 90 minutes with fierceness, anger, sarcasm and humor, making for the most powerful theater on the Great White Way this season, or any other in recent memory.

Two weeks into preview performances, with tweaking taking place daily before the April 22 opening at the Walter Kerr Theatre, Tóibín and director Deborah Warner spoke in separate phone interviews about developing this piece, a one-woman play starring Fiona Shaw, the Irish actress acclaimed for her work on British and New York stages who recently has appeared as Petunia Dursley, Harry Potter’s annoying aunt, and as Marnie Stonebrook in HBO’s “True Blood.”

“The Testament of Mary” has been nominated for three Tony awards, including Best Play. It was set to close May 5.

“We were able to develop it when we saw it as storytelling,” Warner said, describing the awesome task of turning a work that was in the form of a novel with one character -- a revered and historical one at that -- into an evening of theater on a vast stage in a Broadway house. “People love having stories told to them. It goes back to Sunday school. That aspect absolutely plays to the child in us in the hands of a great storyteller. We really give ourselves over.”

Not that “Testament” is a story for children. Shaw’s portrayal of Mary’s guilt and her agonized memories of watching her son’s suffering as he was nailed to the cross are raw. She draws the audience in, leaving them transfixed.

“Everybody in the theater is silent,” Warner said. “The density of silence is everybody working through their understanding of the story. It’s an extraordinary thing happening at the same time, their parallel experiences of the story. It’s different for everybody.”

Bringing this realism to life was an excruciating journey for Tóibín, a self-described lapsed Irish Catholic who no longer believes in God. While creating the passages of Mary’s memory of the crucifixion he only wrote when other people were in the house and always kept the door open. One particularly vivid image is that after Jesus’ first arm is nailed to the cross and he roars in agony, he fights so hard to hold his other arm on his chest that other men have to come pry it off to nail it.

“I had to imagine it to the fullest,” Tóibín said. “I couldn’t just write it. I had to almost see it.”

When he emerged one day after writing, a friend looked at his face and asked with concerned, “Are you all right?”

Tóibín, who lives part of the year in New York while teaching English literature at Columbia University, was inspired to give Mary a voice by two paintings he had seen in Venice -- Titian’s “The Assumption of the Virgin” and a Tintoretto painting of the crucifixion. As a child, kneeling daily with his family to pray the rosary, Mary had not only been the Queen of Heaven, but the Queen of Ireland as well. He realized that, other than the Magnificat, “a literary convention,” she had for the most part been silent throughout the Gospels.

The trick was to find the right voice. She had to live in a real house, “but not the house next door.” She would have to have grandeur in her tone, as well as deep fragility, with nothing in between.

“She’s not a housewife,” he said. “I couldn’t bring her down, she’s not someone you see in the store. That regal thing had to be there.”

For this reason, she had to be alone onstage. She recounts her arguments with the disciples -- they are trying to get her to verify their accounts of her son’s life so they can start a new movement and she refuses -- but no ordinariness of somebody making tea and moving about could disrupt her story.

This presented a challenge to the actor and director. Warner meets it by allowing the audience to take the place of other characters. Before the show they are encouraged to go onstage, walk around the set and handle the props. This device brings to life the sense of restlessness and ferment described in the book as surrounding the crucifixion.

The lines of people waiting to go onstage remind Warner of people on a pilgrimage.

“The audience is in partnership. They have a relationship with her before she appears,” she says, adding that people had had a relationship with Mary’s son that caused crowds to follow him. “The challenge is to surprise people to be more open to listen and hear. He had been a success, people flooded to where he was. That’s harder to get with just one of you onstage.”

Tony-nominated sound designer Mel Mercier enhances this feeling of a Middle Eastern landscape with original music and the sounds of movement and animals and marketplace noises.

Interestingly, as in the novella, Jesus’ name is never mentioned. Mary refers to him as “my son” or “the one who was here.” Tóibín had two specific reasons for this.

“First of all, I couldn’t bring myself to do it,” he said. “That was moving into space I didn’t want to go to. I didn’t want to make the name ordinary.”

Secondly, he was struck by something he discovered while researching his book Lady Gregory’s Toothbrush. As he read the papers of this great patron of the theater in Ireland at the New York Public Library, he noticed that after her son, Robert, had been shot down over Italy in 1918 during World War I she never mentioned his name again in her letters. Tóibín realized it must have been too painful for her.

The Mary that Tóibín has created shares this pain, although in far greater measure because of her guilt at not staying until her son died, at not having done anything to stop his public preaching, which she found annoying -- “his voice all false and his tone all stilted” -- and her rage at the disciples for trying to make of his death something it was not. No one will listen to her memories because they don’t confirm the story the followers are preparing to spread, so she roams her home alone, reliving the truth for herself.

By the end of the show, she turns this rage on the disciples.

“I was there,” she tells them. “I fled before it was over but if you want witnesses then I am one and I can tell you now, when you say that he redeemed the world, I will say that it was not worth it. It was not worth it.”

Although Tóibín is no longer a believing Catholic, he is grateful for his upbringing in the tradition and sees no negative influences.

“The iconography and language and experience stays with you and can be summoned up easily,” he said. “It gave you an extraordinarily rich way of perceiving beauty in the world.”

When asked how he wanted people to see Mary, he paused before saying he’s not a theologian, that he used his imagination and is not trying to convince anyone.

“I’m just a poor fiction writer. All I was trying to do was find a voice I thought would be credible during that time at the theater. I am in the business of creating images which are fictional. That’s powerful.”

He says he has received no hate mail, only a few e-mails that were divided between people who were upset or who wanted to debate. The responses on Amazon were angrier, he added. About 50 protesters organized by the American Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family, and Property, a conservative Catholic organization based in Pennsylvania, gathered in front of the theater before the first preview. An earlier version of the show was performed in Dublin without protest.

While director Warner has collaborated theatrically with Shaw for a quarter century, this is the first of their efforts to premiere in the United States. Having grown up as a Quaker in England, her only association with Mary was “mostly through 2,000 years of art history.”

“There’s something about the guise of the story that’s right,” she said. “It’s contemplative and a jolly good story at the same time. It’s not a traditional Broadway show, but great storytelling is part of the Broadway tradition.”

Tóibín hopes audiences will experience the show in their nervous systems, bypassing their intellect.

“I want them to have an experience in the theater that will matter to them.”

[Retta Blaney is the author of Working on the Inside: The Spiritual Life Through the Eyes of Actors.]

ON THE WEB

“The Testament of Mary”

www.testamentonbroadway.com